03.11.2017

Palestinians around the world are marking 100 years since the Balfour Declaration (“Balfour’s Promise” in Arabic) was issued on November 2, 1917. A public pledge by Britain for “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people”, the declaration marks the beginning of a century of injustice for the Palestinian people. For the declaration of the British government promised the Zionist movement a country that did not belong to it, thus ignoring the political and national rights of the resident Palestinian population.

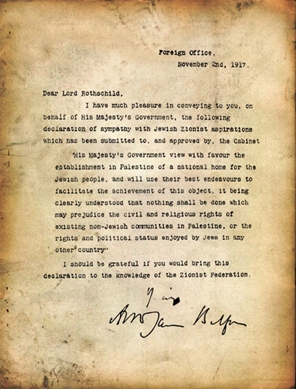

The pledge came in the form of a letter written on behalf of the British government by the then British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour to Lord Walter Rothschild, a figurehead of the British Jewish community, for circulation among the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland. The Balfour Declaration is regarded as main catalysts for the Nakba – the ethnic cleansing of Palestine in 1948, the creation of the Zionist State of Israel, and for the persistent expropriation, expulsion and uprooting of the Palestinian people, which lost sovereignty over their country and continue to be denied their right to self-determination. The dire consequences of the Balfour Declaration continue to affect the Palestinian people every single day, with the Israeli occupation of Palestine since 1967 constituting the longest-lasting military occupation in the world. Not only is Palestinians’ right to self-determination persistently denied, Israel also continues to seize Palestinian land through their illegal settler colonialist activities and submits the entire Palestinian population to an entrenched system of institutionalized discrimination.

Provisions of the Balfour Declaration

In an infringement of the principle of self-determination, the Balfour Declaration of 2 November 1917 expressed support for the Zionist endeavor and Jewish political rights in Palestine, while limiting the rights of the indigenous Palestinian population – referred to as “existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine” although they comprised the vast majority of the local population – to civil and religious rights. The Declaration read:

In an infringement of the principle of self-determination, the Balfour Declaration of 2 November 1917 expressed support for the Zionist endeavor and Jewish political rights in Palestine, while limiting the rights of the indigenous Palestinian population – referred to as “existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine” although they comprised the vast majority of the local population – to civil and religious rights. The Declaration read:

His Majesty’s government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

While Britain did not possess any moral or legal grounds for promising Palestine to the Jewish people as “national home”, a concept that is not entailed in international law, the provision was incorporated in the terms of the British Mandate for Palestine subsequent to the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire after World War I (1914-1918).

An immediate consequence of the Declaration was growing popular support for Zionist aims in Palestine. Two years later, it would serve as basis for the creation of Mandatory Palestine. In 1948, its provisions would materialize in the creation of the State of Israel amidst the dispossession, expulsion, oppression and killing of the indigenous Palestinian population.

Imperialist Ambitions and Human Plight

The fundamental flaw of the Balfour Declaration is thus, as Arthur Koestler put it, that “one nation, solemnly promised to a second nation, the country of a third”. More precisely, it was a weighty pledge made by a European power about a territory towards which it had neither legal nor moral claims, in blatant disregard of the presence and wishes of the overwhelming native majority population of that territory. Only fatally limited provisions were enshrined with regards to the indigenous Palestinian population, which accounted for more than 90 percent of the population of Palestine, then under Ottoman rule, promised by the British to a Jewish population of less than 10 percent. Hence, they provided the Jewish people – a minority in Palestine and otherwise foreign nationals – the right to national self-determination, while denying self-determination to the native majority. The Balfour Declaration thus classifies as typical colonial document, which omitted the rights and aspirations of the people of the country.

The driving force behind the Balfour Declaration was British imperial considerations and self-interest rather than genuine concern for the aspirations of the Jewish people. At the time of its drafting, Britain was involved in the Second World War and was far from winning, so it desperately sought growing support – which it reckoned it may gain from the Jewish by supporting Zionist ventures. In particular, it was deemed important to rally support among Jews in the United States and Russia, who in turn could help ensure their governments’ continued involvement in the war. Within Britain, the Zionist lobby was small yet had some degree of influence and ties existed between the British Zionist community and the government. Curiously, the first draft of the Balfour Declaration was submitted by the British Zionist leader Dr. Chaim Weizmann. British officials, first and foremost among them British Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour, soon realized that British support for Zionist ambitions could further their imperialist agenda.

The assumption that a perceived united Jewish entity with vast influence in the European sphere would turn the tides of war was rife with anti-Semitism. Yet, Zionist leaders eagerly cooperated with their European counterparts. However, the national Zionist objective of establishing a Jewish state in Palestine was far from being unanimous among European Jews. Indeed, many vehemently opposed the movement and regarded it as undermining their civil and political rights in their European home countries.

Apart from attempting to win a war by warranting Jewish support, the British followed their colonialist ambitions. Imperial powers such as Britain relied on a policy of planting European settlers in colonial territories to police and administer their empires. Such pursuit would permit no equal rights in the land for the indigenous inhabitants.

An earlier sinister agreement between high-ranking British diplomat Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot of France (Sykes–Picot Agreement) had determined that Palestine would be under shared British and French influence or international administration. Therefore, it was reckoned that the Balfour Declaration could further British strategic imperial interest in Palestine, particularly by keeping Egypt and the Suez Canal within its sphere of influence.

The Precursor: Sykes-Picot Agreement

Just a year earlier, the Sykes-Picot Agreement had been secretly introduced, whose terms had been negotiated by British diplomat Mark Sykes and French counterpart François Georges-Picot. Russia was informed of the agreement as it, too, was to receive a piece of the Ottoman cake. After the prospective defeat of the Ottomans, their territories, including Palestine, would be divided among the victorious parties.

Just a year earlier, the Sykes-Picot Agreement had been secretly introduced, whose terms had been negotiated by British diplomat Mark Sykes and French counterpart François Georges-Picot. Russia was informed of the agreement as it, too, was to receive a piece of the Ottoman cake. After the prospective defeat of the Ottomans, their territories, including Palestine, would be divided among the victorious parties.

The centerpiece of the agreement was a map of Southwestern Asia marked with straight pencil lines, which delineated the Triple Entente’s mutually agreed spheres of influence and control over the Arab populations. These were divided based on haphazard assumptions of tribal and sectarian lines. The agreement completely disregarded immanent repercussions of slicing up distinct civilizations with a dynamic history of cooperation and conflict.

While British and French mandates were extended over divided Arab entities, Palestine was soon to be designated as “homeland” for the Jewish people, condemning the Palestinian people to perpetual war and turmoil.

British Mandate in Palestine

Unlike in the other post-war mandates, the British mandate in Palestine was to foster conditions for the establishment of a Jewish “national home”. Upon the imposition of the mandate, the British thus fueled immigration of European Jews to Palestine. Between 1922 and 1935, the Jewish population increased from nine percent to almost 27 percent of the total population. Although the Balfour Declaration included the limited provisions of “civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities” – which were to be neglected in the century to come –, the mandate contained all necessary tools for the Jewish to establish self-rule at the expense of Palestinians.

Already at the inception of Jewish migration to Palestine in 1882, European countries vigorously facilitated the movement of settlers to establish colonies to safeguard their geostrategic and economic interests. As Arabs were fighting the Ottoman Empire alongside the British, they were promised independence upon victory. Arab leaders expected that Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations would apply to Arab entities under Ottoman rule, which were promised that they were to be respected as “a sacred trust of civilization”, and their communities were to be recognized as “independent nations”. Palestinians shared such aspirations for long-coveted self-determination. This was particularly reflected in their role as voting delegates in support of the Pan-Arab Congress in July 1919, which elected Faisal as a King of a state comprising Palestine, Lebanon, Transjordan and Syria, and their backing of Sharif Hussein of Mecca.

When British intentions and their ties with the Zionist nationalist movement became obvious, Palestinians started their rebellion – which would carry on for a century to come. Already in 1920, the Third Palestinian Congress in Haifa deplored the British government’s rapports with the Zionist project and rejected the Balfour Declaration as a violation of international law and of the inalienable rights of the indigenous population.

In July 1922, the League of Nations approved the terms of the British Mandate over Palestine without consulting the native Palestinian population, whose inalienable rights and political aspirations would be neglected by the British and international community for decades to come, only to occasionally appear as negligible rioters and obstacles to the British-Zionist colonial dealings. The Balfour Declaration had thus laid the ground for the massive ethnic cleansing that would follow three decades later. As Walid Khalidi pointedly expressed:

| “The Mandate, as a whole, was seen by the Palestinians as an Anglo-Zionist condominium and its terms as instrument for the implementation of the Zionist programme; it had been imposed on them by force, and they considered it to be both morally and legally invalid. The Palestinians constituted the vast majority of the population and owned the bulk of the land.”1 |

While the Palestine Mandate was designated by the League of Nations to provide administrative guidance for the transition to full independence, it was inconsistent with the upheld principles of the Covenant: Great Britain as Mandatory Power soon promoted the idea of a “Jewish national home” in Palestine, due to assurances given to the Zionist Organization, and fostered Jewish immigration in complete disregard of the wishes of the indigenous Palestinian Arab majority.

When the British became cognizant of the havoc they had caused, they proposed partitioning Palestine into separate Arab and Jewish states – a proposition that was resisted fervently by the Palestinian population through a three-year revolt between 1936 and 1939. It was a full-fledged nationalist uprising against British rule, demanding independence and the end of Jewish immigration.

The British government reconsidered its position and published a policy document in May 1939 known as “White Paper”, which recommended abandoning the partition of Palestine into two states and instead called for an independent Palestine in which Arabs and Jews would share government. Moreover, it limited Jewish immigration and determined that the Arab majority would set future immigration levels. Lastly, it clarified that Balfour had not intended to create a Jewish state at the expense of the native Arab population. Following opposition on several fronts and preoccupation with World War II, however, the White Paper was withdrawn and was never to surface again.

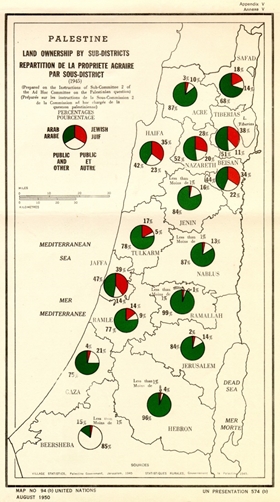

When the Mandatory Power in its 1939 Statement of Policy expressed the irreconcilability of the conflicting terms (“dual obligation”) of its Mandate and declared its end, recommending that Palestine be an independent and unified country which guarantees the rights of minorities, Zionist opposition, the Second World War, and large-scale Jewish immigration resulting from the horrors of the Holocaust thwarted the implementation of the provisions. The Palestinian people resisted the denial of their self-determination and the effects of large-scale immigration with a number of revolts. While the Jewish had accounted for 9 percent of the population in Palestine in 1917, substantial immigration had led to an increase to 32 percent in 1947. 6.2 percent of the land was owned by the Jewish, whilst before Jewish land ownership had constituted 2.5 percent. The Palestinian demand for the realization of their natural rights was now confronted with the demands for a “national home” of a sizeable and powerful minority.

When the Mandatory Power in its 1939 Statement of Policy expressed the irreconcilability of the conflicting terms (“dual obligation”) of its Mandate and declared its end, recommending that Palestine be an independent and unified country which guarantees the rights of minorities, Zionist opposition, the Second World War, and large-scale Jewish immigration resulting from the horrors of the Holocaust thwarted the implementation of the provisions. The Palestinian people resisted the denial of their self-determination and the effects of large-scale immigration with a number of revolts. While the Jewish had accounted for 9 percent of the population in Palestine in 1917, substantial immigration had led to an increase to 32 percent in 1947. 6.2 percent of the land was owned by the Jewish, whilst before Jewish land ownership had constituted 2.5 percent. The Palestinian demand for the realization of their natural rights was now confronted with the demands for a “national home” of a sizeable and powerful minority.

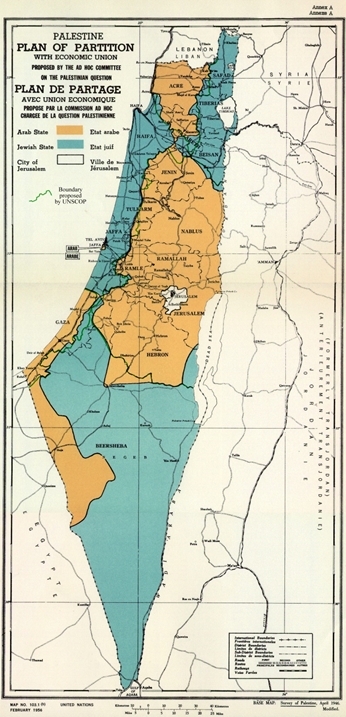

Referral of the Palestine Question to the United Nations and Partition

The Mandatory Power, unable to deal with its “dual obligation” and the ensuing violent conflict, conferred the Palestine question to the UN, which recommended the partition of Palestine. This recommendation was incongruent with the principle of self-determination enshrined in the UN Charter, which would have followed the political aspirations of the majority with guarantees for the rights of the minority. Besides, the recommendation of partition on Palestine against the explicit wishes of the majority of its population was in contravention to the Mandate, which postulated that “no Palestine territory shall be ceded or leased to, or in any way placed under the control of, the government of any foreign power” (Article 5) and that the control would, after the termination of the Mandated temporary restriction of sovereignty, be conferred to “the Government of Palestine” (Article 28). The General Assembly adopted the Plan as Resolution 181(II) on 29 November 1947, designating over half of the territory of Palestine to the Jewish minority.

While the partition plan was not formally implemented by the UN, the State of Israel was established and expanded its territorial control far beyond the borders allocated by the partition resolution until it occupied 77 percent of the territory of Palestine in the 1948 war, also occupying large parts of Jerusalem, which was to be internationalized under the resolution. The remaining parts of the territory were occupied by Jordan and Egypt. By the end of 1949, more than half (726,000) of the indigenous Palestinian population had fled or had been expelled. The General Assembly issued its resolution 194 (III) on 11 December 1948, which laid the basis for the treatment of the Palestine issue as “refugee problem” by the UN while neglecting for the next twenty years the thwarted self-determination of the Palestinian people. (DPR, 1979)

While the partition plan was not formally implemented by the UN, the State of Israel was established and expanded its territorial control far beyond the borders allocated by the partition resolution until it occupied 77 percent of the territory of Palestine in the 1948 war, also occupying large parts of Jerusalem, which was to be internationalized under the resolution. The remaining parts of the territory were occupied by Jordan and Egypt. By the end of 1949, more than half (726,000) of the indigenous Palestinian population had fled or had been expelled. The General Assembly issued its resolution 194 (III) on 11 December 1948, which laid the basis for the treatment of the Palestine issue as “refugee problem” by the UN while neglecting for the next twenty years the thwarted self-determination of the Palestinian people. (DPR, 1979)

Although Balfour cannot be blamed for all grave injustices Palestinians have suffered, the fundamental flaws of the “promise”, that is the complete omission of the rights and aspirations of the Palestinian Arab people, would inform British, and subsequently Israeli and US, policy henceforth. The striking inequality built into the very fabric of the current geopolitical situation in Palestine and Israel thus persists and the conflict is perpetuated. Meanwhile, Palestinians will continue to resist for as long as the foundations that inspired their rebellion a century ago are not dismantled.

A hundred years later, the impact of the Declaration still reverberates across the Middle East. To Palestinians, it still represents the instant in which an imperial power pledged their land to another people. Expulsion, oppression, and occupation would soon follow.

Britain’s Colonial Legacy

The centenary of the Balfour Declaration is a stark reminder of Britain’s colonial legacy – its “divide and rule” tactics and violent oppression of opposition to its rule – which has left bloody footprints not only in Palestine but also in Kashmir and Myanmar and requires urgent redress. Sincere apologies are still lacking, while effective action to redress the inflicted injustices and suffering are nothing but distant hopes.

By the time the British decided to terminate their mandate in 1947 and bequeathed the United Nations with the Palestine question, the Jewish had already formed an army out of armed paramilitary groups trained by the British. Moreover, the British had allowed the Jewish to establish self-governing institutions, including the Jewish Agency, which would pave the way for state building. By contrast, the Palestinians had been prohibited from acquiring armament and from forming institutions, which led to the 1948 Nakba and the forcible expulsion of more than 750,000 Palestinians from their homeland.

Furthermore, the British Mandate provided fertile ground for the Israeli occupation. In an effort to quell the Palestinian nationalist movement opposing British rule and support for immense Jewish immigration, the British employed reprisals and collective punishment, including night squads, punitive house demolitions, and administrative detention.

The 1930s were also marked by intense collaboration between the British and Jewish fighters, predominantly the Haganah paramilitary group, which was the largest Zionist militia in Palestine that would later become central to the Israeli army. British brutality taught Jewish soldiers how to violently oppress insurgencies within a colonial legal framework of collective punishment and punitive action. The relevant legal framework, the British emergency laws applied in 1945, are firmly in place today and employed by Israel in its brutal military occupation of the remaining Palestinian territories.

Today, Israel profits from unwavering military and economic support by its Western allies. Britain and Israel have even intensified their intelligence cooperation in recent years. Elbit Systems, a leading Israeli weapons producer with numerous branches in the UK, recently declared the UK as “home market” for its products. Together with CAE, the company will pursue British Ministry of Defence training opportunities. Moreover, the British army has commissioned the most extensive drone program in Europe, which is based on Israeli-designed weapons that have undoubtedly been tested against Palestinians.

A Century On

A century later, the British government remains unrepentant, refusing to apologize for its role in exacerbating the Palestinian plight. Indeed, British Prime Minister Theresa May does the opposite by celebrating the centenary of the Balfour Declaration at an elegant London venue with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Retrospectively, the Balfour Declaration may well enable Europeans to ease their conscience about the horrific murder of six million Jews in Europe during World War II. From this perspective, the support for the “establishment of a national home for the Jewish people” seems noble and worthy of pride – if it did not distract from British and Western imperial ambitions and the brutal reality that would unfold under its aegis. Until this day, declaring oneself a Zionist remains a rite of passage for Western leaders and any criticism towards Israel’s illegal policies and practices is condemned as “anti-Israel” or even, shamefully, “anti-Semitic”.

The absurdity of equaling anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism becomes particularly striking in the thoughts of Jewish critics of Israel, who vehemently oppose Israeli oppression of Palestinians and are unable to reconcile their Jewish beliefs with Zionist ones. As Barnaby Raine, PhD student at Columbia University, explained to Aljazeera: “We as Jews are religiously committed to ‘tikkun olam’, ‘mending the world’, and for centuries Jews have stood at the forefront of struggles against oppression and exploitation.” Those following universalist currents in Jewish politics joined by all those believing in universal human rights must stand up against the oppression Palestinians are facing.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The policy of the British mandate was intended to facilitate the Zionist movements’ creation of the State of Israel as a pivot of control not only in Palestine but the entire Middle East. Instead of ensuring promised Palestinian self-determination, Britain facilitated their expulsion and continued exile and oppression. The circumstances surrounding the establishment of Israel, however, remain obscured in public discourse until this day and mask the suffering of the Palestinian people. Indeed, Britain entrenches their suffering through rigorous intelligence and military cooperation with the Israeli government. Balfour’s legacy is carried on by multiple “Western democracies” through support of and complicity in Israel’s brutal occupation and oppression of the Palestinian people and an ever-expanding graveyard of the conflict’s victims.

It is high time that Britain – instead of celebrating the ominous Balfour Declaration – take measures of moral responsibility and effective action for its contribution to the plight of the Palestinian people and the volatile reality in the region. All other relevant States must also cease their complicity in committed violations of human rights and international law, including the right to self-determination.

A just solution to the Palestine question and the exercise of Palestinians’ inalienable rights remain cornerstones for lasting peace and stability in the Middle East and require significant contribution by neighboring Arab States, which can build on the Arab Peace Initiative. GICJ urges the Security Council, as primary organ promoting peace and security under the UN Charter, and the General Assembly to play a constructive role by reaffirming the long-standing parameters for a just peace based on relevant UN resolutions. Rather than “managing” the conflict and “merely” alleviating the humanitarian crisis, the international community needs to mobilize its political will to implement the longstanding principles. We therefore recommend to the UN Security Council to:

Urge all Member States, international organizations, and companies to cooperate to end the Israeli occupation and illegal policies and practices by considering appropriate measures to exert pressure on Israel, inter alia, by ceasing their complicity. In particular, GICJ calls for the suspension of the EU-Israel Association Agreement, the US-Israel Free Trade Agreement, and the rescindment of all military cooperation. Specifically, we recommend to the Security Council to:

• Call on Member States to cease all forms of military, police or intelligence cooperation with the Israeli authorities;

• Advise Member States to impose sanctions on Israel.

Self-determination constitutes a jus cogens norm and is enshrined in Article 1 of the UN Charter. The lapse of time does not extinguish this right because, just as the rights to life, freedom and identity, it cannot be waived. Bearing in mind that the international community, its members and institutions, have an obligation to act where international law, including human rights and especially the right to self-determination, is violated, we recommend to the United Nations, its Members States, and relevant institutions to comply with their international obligations and:

• Take all necessary measures to finally bring an end to the prolonged occupation of Palestine and fulfill Palestinians’ right to national self-determination, which involves the end of all annexationist and settlement activity and the illegal and destructive blockade on Gaza, which constitutes a form of collective punishment, the lifting of all closures within the framework of Security Council resolution 1860 (2009), and the guarantee of the unrestricted movement of persons and goods between the West Bank and Gaza.

1. Khalidi, W. (1984). Before Their Diaspora. Institute for Palestine Studies.

Recent GICJ features on Palestine:

|

|

|

|

GICJ Activities on the Human Rights situation in Palestine and other occupied Arab territories

GICJ Urgent Appeals on Palestine:

- GICJ - Punishing people for the misdeeds of others clearly violates international law - July 2014

- A match in the powder keg: The occupying force continues to contravene international law - April 2014

- GICJ – Urgent Appeal on the Forcible eviction of Ein Hijleh - February 2014

- UN press release on behalf of Issa Amro - September 2013

- GICJ –Urgent appeal following arbitrary arrest of Sireen Khudiri - June 2013

- GICJ – Follow-up appeal on behalf of HR defender - June 2013

- GICJ - Follow-up appeal on the case of Mr. Issa Amro - April 2013

- GICJ - Urgent Appeal to the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders - March 2013

- GICJ – Urgent Appeal to the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Palestinian territories occupied since 1967 - February 2013

GICJ Side-Events and oral statements on Palestine:

Human Rights Council - 30th regular session (14 September - 2 October 2015)

Human Rights Council - 29th regular session (15 June - 3 July 2015)

Human Rights Council - 21st special session on the human rights situation in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem (23 July 2014)

Human Rights Council - 26th regular session (10 - 27 June 2014):

Human Rights Council - 25th regular session (3 - 28 March 2014):

Human Rights Council - 24th regular session (9 - 27 September 2013):

- Side-event: Human Rights in Palestine - Palestinian Refugees in Diaspora and their Right of Return, Where to?

- Side-event: Human Rights in Middle East - Give Peace a chance

- Democracy and the Right to self-determination

- GICJ statements on Palestine

Human Rights Council - 23rd regular session (27 May - 14 June 2013):