02.11.2018

By: Mutua K. Kobia

“Every journalist killed or neutralized by terror is an observer less of the human condition. Every attack distorts reality by creating a climate of fear and self-censorship”

Barry James, Press Freedom: Safety of Journalists and Impunity.

INTRODUCTION

From 2006 to 2017 about 1010 journalists have been killed for providing information to the public and reporting the news. In almost all cases the perpetrators enjoy impunity and their crimes go unpunished. This worsens the situation as it only leads to more deaths and further limits information and news reaching the public.

November 2 was proclaimed The International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists under Resolution A/RES/68/163 which was adopted by the General Assembly at its 68th Session in 2013. The Resolution acknowledges that journalism continuously evolves to include inputs from private individuals, media institutions and a range of organisations seeking to receive and transmit all kinds of ideas and information both online and offline, in exercising freedom of opinion and in accordance with Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)1. The Resolution also bears in mind that one of the main challenges toward strengthening the protection of journalists is impunity for attacks against journalists. The Resolution condemns all attacks and acts of intimidation against journalists and media workers including the most serious of attacks such as torture, extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, and arbitrary detention.

Finally, the Resolution urges Member States to prevent any violence against journalists and media workers and that perpetrators must be brought to account through speedy, impartial, and effective investigations into any allegations of such violence. Furthermore, victims must have access to appropriate remedies. The Resolution calls on all states to:

“promote a safe and enabling environment for journalists to perform their work independently and without undue interference, including by means of:

(a) legislative measures;

(b) awareness-raising in the judiciary and among law enforcement officers and military personnel, as well as among journalists and in civil society, regarding international human rights and humanitarian law obligations and commitments relating to the safety of journalists;

(c) the monitoring and reporting of attacks against journalists;

(d) publicly condemning attacks; and

(e) dedicating the resources necessary to investigate and prosecute such attacks”

The then High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, in his global update of human rights concerns during the 37th Regular Session of the Human Rights Council (March 2018), raised concerns about the rights and lives of journalists. He was very much concerned about reports received by his Office concerning rights violations and abuses against journalists in several countries. He specifically mentioned arrests and prosecutions of journalists in Iran; arrests and detention in Sudan; ongoing targeting of journalists in Egypt; threats and intimidation against journalists in Honduras; dramatic erosion of freedom of the press where “journalists have in recent months faced escalating intimidation, harassment, and death threats” in Myanmar; legal provisions used to silence journalists in Cambodia; deepening repression and increased threats to journalists in the Philippines; judicial harassment and intimidation in continued restrictions on freedom of expression in Thailand; and violence against independent voices and journalists in Pakistan.

|

Facts and Figures 2006-2017

[Source: Unesco.org] |

CRIMES AGAINST JOURNALISTS IN BURUNDI AND IRAQ

Geneva International Centre for Justice highlighted crimes against journalists in specific countries.

BURUNDI

In 2013, the president of Burundi approved a new media law. Since 2014, the Burundian government became quite hostile towards independent journalists. In 2016, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) was aware of at least 100 journalists who were forced to flee the country.

In October 2016 the Interior Minister of Burundi, Pascal Barandagiye suspended the permits of several organisations of the Burundian Union of Journalists. In addition to jailing journalists, this move severely restricts freedom of expression and opinion in Burundi.

On 27 August 2018 journalists were barred from investigating reports of a standoff between residents, who claimed they had not been paid expropriation fees, and the police. The journalists claimed that after introducing themselves to the police and showing their badges, they were surrounded by the police and blocked from speaking with the residents. They were then victims of intimidation as the police hit one of the them with the butt of his gun, slapped them, and attempted to take away the journalists’ equipment. Fortunately, they were able to escape with only minor injuries and their equipment after the residents demanded the police officers to stop harassing the journalists.

CPJ contacted a police spokesperson who directed them to a video that showed him denying police assault against the journalists. Moreover, they accused the journalists of not properly identifying themselves and it was them who attempted to use force to cover the case. A news report cited the ministry of public security who echoed the police accounts and added that the journalists supported one of the parties in the conflict.2

In May 2018 authorities in Burundi banned the BBC and Voice of America (VOA) only weeks before a critical referendum on presidential term limits was to take place. The referendum was to extend the presidential term, in this instance it could extend current president, Pierre Nkurunziza’s rule to 2034. According to the National Communication Council, the media organizations were suspended for six months. They were accused of unprofessional conduct and breaching press laws.

They also said that the BBC brought a Burundian national on their program and made remarks that were “inappropriate, exaggerated, non-verified, damaging the reputation of the head of state, to ethnic hatred, to political conflict and civil disobedience.”3

IRAQ

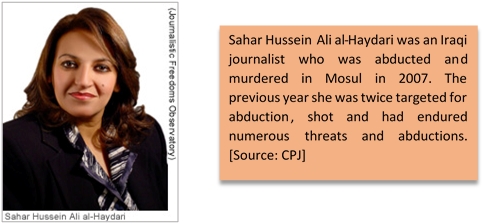

Since 2003 Iraq became a very dangerous place for journalists. In 2007 the Committee to Protect Journalists noted that at least 106 journalists and 39 media support staffers were killed in Iraq since the US-led invasion in 2003. About four in five media deaths recorded by CPJ were Iraqis during the invasion and occupation. In armed conflict and post conflict situations the Forum of Iraqi Female Journalists documented names of 23 Iraqi female journalists who were assassinated between a ten-year span (2003 and 2013). This was in addition to other forms of violations such as cases of assault, intimidation, and forced displacement.

In a 2016 report by the International Federation of Journalists Iraq was named as the most dangerous country in the world for journalists. They noted that over 300 journalists were killed between 1990 and 2015. Journalists are targeted especially when they openly criticise officials of their corruption. They face various types of violations, abuses, and threats such as beatings, harassment, and prosecution. On 24 April 2015, the Iraqi Observatory for Press Freedom against journalists registered eight cases of “assault, expulsion, threats and incitement to murder” against journalists who were covering anti-government demonstrations in Baghdad, Basra, Diyala, and Samawa. Despite these developments perpetrators often enjoy impunity.

In addition to threats and intimidation authorities seek other ways to silence the press. The Iraqi Communications and Media Commission removed the operating license of al-Baghdadia TV in March 2016 and of Al-Jazeera in April 2016 supposedly because of “media rhetoric that incites sectarianism and violence”.4

The Iraqi Women Journalists Forum prepared a questionnaire on the extent of harassment faced by women in the media. They found that 68% of women answered 'yes', 11% answered sometimes, and 21% answered 'no'.5

JAMAL KHASHOGGI

In October 2018 Jamal Khashoggi, a Saudi-American journalist who worked at the Washington Post, was killed when during his visit to the Saudi Arabian Consulate in Istanbul, Turkey to pick up marriage documents. Istanbul’s chief prosecutor said that Khashoggi was suffocated in a premeditated killing and that his body was then dismembered and disposed of. The brutal murder is thought to have been perpetrated by an 18-member team from Saudi Arabia.

[Photo Source: Washington Post]

PREVENTING IMPUNITY

UN PLAN OF ACTION ON THE SAFETY OF JOURNALISTS AND THE ISSUE OF IMPUNITY

The ‘United Nations Plan on Safety for Journalists’ (hereafter UN Plan) promotes the safety of journalists and fights impunity by calling for prevention mechanisms and actions that address the root causes of violence against journalists and of impunity. It also says that international legal instruments that are internationally recognized and often legally binding, are key tools that the international community and the UN can use for the safety of journalists and to fight impunity. Some of the relevant conventions, declarations, and resolutions include the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; the Geneva Conventions; the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR); UN Commission on Human Rights Resolution 2005/81; and the UN Security Council Resolution 1738 (2006).

The UN Plan also notes that regional systems are reinforced by monitoring bodies that calls attention to violations and observes state-compliance in accordance with their commitments. Agencies, funds, and programmes of the UN system also work toward promoting the safety of journalists and addresses impunity at the national level. It also recognizes that Member States have the responsibility of investigating crimes against journalists.

The UN Plan acknowledges that acts of violence and intimidation are becoming more frequent and have become more varied including threats posed by non-state actors, for example, the growing threat by terrorist organisations and criminal enterprises. Thus, different legal instruments must be made readily available to ensure the protection of journalists. As well, further investigation is needed to address dangers faced by journalists in situations that do not qualify as armed conflicts, for instance, “sustained confrontation between organized crime groups”.

The UN Plan also address female journalists who also face increasing dangers and thus highlights the need for a gender-sensitive approach. Female journalists often face the risk of sexual assault when on duty and in some instances, assault comes in the form of targeted sexual violation, which is often in reprisal for their work. They also face mob-related sexual violence when covering public events and face sexual abuse in detention or captivity. Due to powerful culture and professional stigmas most of these crimes are not reported and violators enjoy impunity.

PRINCIPLES OF THE UN PLAN OF ACTION

The proposed Action plan is based on the following principles:

3.1. Joint action in the spirit of enhancing system-wide efficiency and coherence;

3.2. Building on the strengths of different agencies to foster synergies and to avoid duplication;

3.3. A results-based approach, prioritizing actions and interventions for maximum impact;

3.4. A human rights-based approach;

3.5. A gender-sensitive approach;

3.6. A disability-sensitive approach;

3.7. Incorporation of the safety of journalists and the struggle against impunity into the United Nation’s broader developmental objectives;

3.8. Implementation of the principles of the February 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness (ownership, alignment, harmonisation, results and mutual accountability);

3.9. Strategic partnerships beyond the UN system, harnessing the initiatives of various international, regional and local organizations dedicated to the safety of journalists and media workers;

3.10. A context-sensitive, multi-disciplinary approach to the root causes of threats to journalists and impunity;

3.11. Robust mechanisms (indicators) for monitoring and evaluating the impact of interventions and strategies reflecting the UN’s core values.

UN RESOLUTION ON THE SAFETY OF JOURNALISTS AND THE ISSUE OF IMPUNITY

On 17 December 2015, the General Assembly at its Seventieth Session adopted Resolution 70/162 on “The Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity”. The Resolution reaffirms the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and recalls relevant international human rights treaties, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, as well as the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 and the Additional Protocols. It is also mindful that the right to freedom of opinion and expression is a human right and guaranteed for all in accordance with Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the ICCPR.

The Resolution also takes note of all relevant reports of the special procedures of the Human Rights Council concerning the safety of journalists. It includes the reports of the Special Rapporteurs on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression and on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions. It also commends the activities of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in regard to the safety of journalists and the issue of impunity.

Good practices with regard to the safety of journalists that was highlighted in the report of the Office of the High Commissioner and submitted to the twenty-fourth session of the Human Rights Council and including the right to privacy in the digital age submitted to the Council’s twenty-seventh session is appreciated in the Resolution. The Resolution acknowledges the continuous evolving nature of journalism, the specific risks faced by women journalists, and the numerous and various forms of attacks against journalist as it expresses deep concern of the growing threat posed by non-state actors, including terrorist groups and criminal organizations.

The Resolution bears in mind that impunity for attacks against journalists is a major challenge and that most attacks go unpunished thus contributing to the recurrence of these crimes. and emphasizes the role of the international community to support efforts toward preventing attacks against journalists.

Finally, the Resolution calls on Member States to effectively implement applicable legal frameworks for the protection of journalists and media workers so as to combat pervasive impunity; for States to create and maintain, in law and practice, an environment that is safe and enabling for journalists to do their work without their work; and for states to corporate relevant United Nations entities and in particular UNESCO among others. Lastly, it invites relevant agencies, organizations, funds and programmes of the United Nations system to actively exchange information regarding the implementation of the United Nations Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity in cooperation with Member States and under the overall coordination of UNESCO.

GICJ POSITION

Geneva International Centre for Justice is very much concerned with crimes against journalists and the impunity of such crimes. Due to the ever-evolving acts of violence and intimidation against journalists GICJ recommends the development of legislation to address the various forms of crimes to silence journalists. Moreover, adequate and efficient measures must be enhanced and implemented to bring the perpetrators to justice.

***

|

“On this day, I pay tribute to journalists who do their jobs every day despite intimidation and threats. Their work – and that of their fallen colleagues – reminds us that truth never dies. Neither must our commitment to the fundamental right to freedom of expression” UN Secretary-General António Guterres |

1. Article 19 of the ICCPR

1. Everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference.

2. Everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression; this right shall include freedom to seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice.

3. The exercise of the rights provided for in paragraph 2 of this article carries with it special duties and responsibilities. It may therefore be subject to certain restrictions, but these shall only be such as are provided by law and are necessary:

(a) For respect of the rights or reputations of others;

(b) For the protection of national security or of public order (ordre public), or of public health or morals.

2. https://cpj.org/2018/09/in-burundi-three-journalists-attacked-and-prevente.php

4. https://www.gicj.org/images/2016/35Session_HRC_Texts/Iraq-A-Silenced-Nation.pdf

5. “Iraqi Women in Armed Conflict and post Conflict Situation”. 2014 https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CEDAW/Shared%20Documents/IRQ/INT_CEDAW_NGO_IRQ_16192_E.pdf

International Days of Remembrance articles by GICJ:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

| International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances |

|

World Refugee Day |

|

|