By Lorenzo Bersellini / GICJ

20 points or nothing

Twenty points that have the potential to alter the lives of millions in Gaza, in Palestine and in the wider Middle Eastern region for decades to come.

Twenty points that have been drafted and presented by US President Donald Trump as the solution for one of the most complex questions the United Nations and the international community have ever faced.

Twenty points that the international community, including high representatives of the UN, upholds and praises, urging Hamas’ leaders to accept them as soon as possible, without any hesitation, in the name of pragmatism.

The peace plan proposed by the US President and already approved by Israel’s Prime Minister has been decried as the best attempt at peace for Palestine so far. Coherent with Trump’s business-like approach to international security, it has been presented as a “take it or leave it” deal for Hamas, which can either accept it or choose “the hard way”, meaning letting Israel complete its military and genocidal campaign in Gaza.

Indeed, the plan includes important elements such as the cessation of hostilities, the release of hostages and illegally detained prisoners on both sides, and the resumption of aid as agreed in the ceasefire deal of January 2025.

However, if agreed upon by all parties, will this agreement lead to a just peace for Palestine and for the whole region, in respect of human rights? Will this agreement truly bring justice to the Palestinians?

Problematising the Peace Deal - There’s more to just 20 points

Governments across the world are struggling under increased pressure from civil society and citizens who oppose the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the system of apartheid recognised by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) affecting the Palestinians. Different forms of protest and civic resistance have intensified, as participants call out governments for their cooperation with Israel’s international crimes and for their failures to respect and protect Palestinian rights.

Governments’ decision to endorse this plan should not come as a surprise, considering it could at least temporarily conclude the massacre and thus diminish some of the mounting domestic pressure.

Nevertheless, the prospect that this plan will concretely help solve the Palestinian’s plight for self-determination and restore peace in the region seems far-fetched.

There are multiple limitations to the presented deal.

First and foremost, fundamental questions should arise from the fact that no Palestinian representative has been involved in the negotiating and drafting phase of this proposed plan. Arguably, this sets the stage for future shortcomings and inviability. On the other hand, the deal was announced in a joint press release by President Trump and Prime Minister Netanyahu following a closed-door meeting in Washington between Israeli and American top officials, raising doubts on the impartiality and neutrality of the outcome.

Besides this first methodological limitation, the object of the peace plan appears to be flawed in its core elements.

The right to self-determination and development of Palestinians

The proposed twenty-point list fails to adequately address the right to self-determination of Palestinians, as recognised by both the UN General Assembly (UNGA) and the ICJ. It presents Palestinian self-determination as a reward for future progressive reforms by the Palestinian Authority and Gaza redevelopment (point 19 of the plan). This framing of the issue completely disregards the inalienability of the Palestinian’s right to self-determination, which by now should have already been achieved and instead is flagrantly violated, and shall definitely not be linked to any sort of political or economic objective to be achieved. This preposition thus violates fundamental obligations and the centrality of the right to self-determination.

Palestinian self-determination is also utterly disregarded in points 9 and 10 of the proposal, in which plans for the creation of a future technocratic body, the so-called “Board of Peace”, and “Trump’s economic development” model are laid out.

The first body will be tasked with the creation of “modern governance” in Gaza under the guidance of Trump, former British PM Tony Blair and other selected heads of states. Authority is expected to be passed over after an indefinite amount of time to the Palestinian Authority, when its reform will be deemed complete. Such a system of supposedly temporary foreign, technocratic governance closely resembles the mandate system established in the Middle East and elsewhere in the world under the League of Nations between WWI and WWII. The model, underscored by colonial and undemocratic practices, was used to guide supposedly underdeveloped peoples towards good governance and civilisation, as they alone could not have achieved so. Such spirit might appear to be guiding the peace plan’s approach towards governance in Gaza, revitalising an anachronistic system opposed to the aspiration of Palestinian self-determination and the current human rights guarantees.

In a similar way, point 10 of the agreement, which presents a development plan for Gaza’s economy, also neglects fundamental tenets of the right to development. The plan aims to drive in investment and new proposals to revitalise the Strip and its development under Trump’s guidance. Nevertheless, it comes again as a form of external imposition and does not seem to include Palestinian participation, or even less Palestinian ownership of their resources.

Beyond Gaza: the West Bank and East Jerusalem

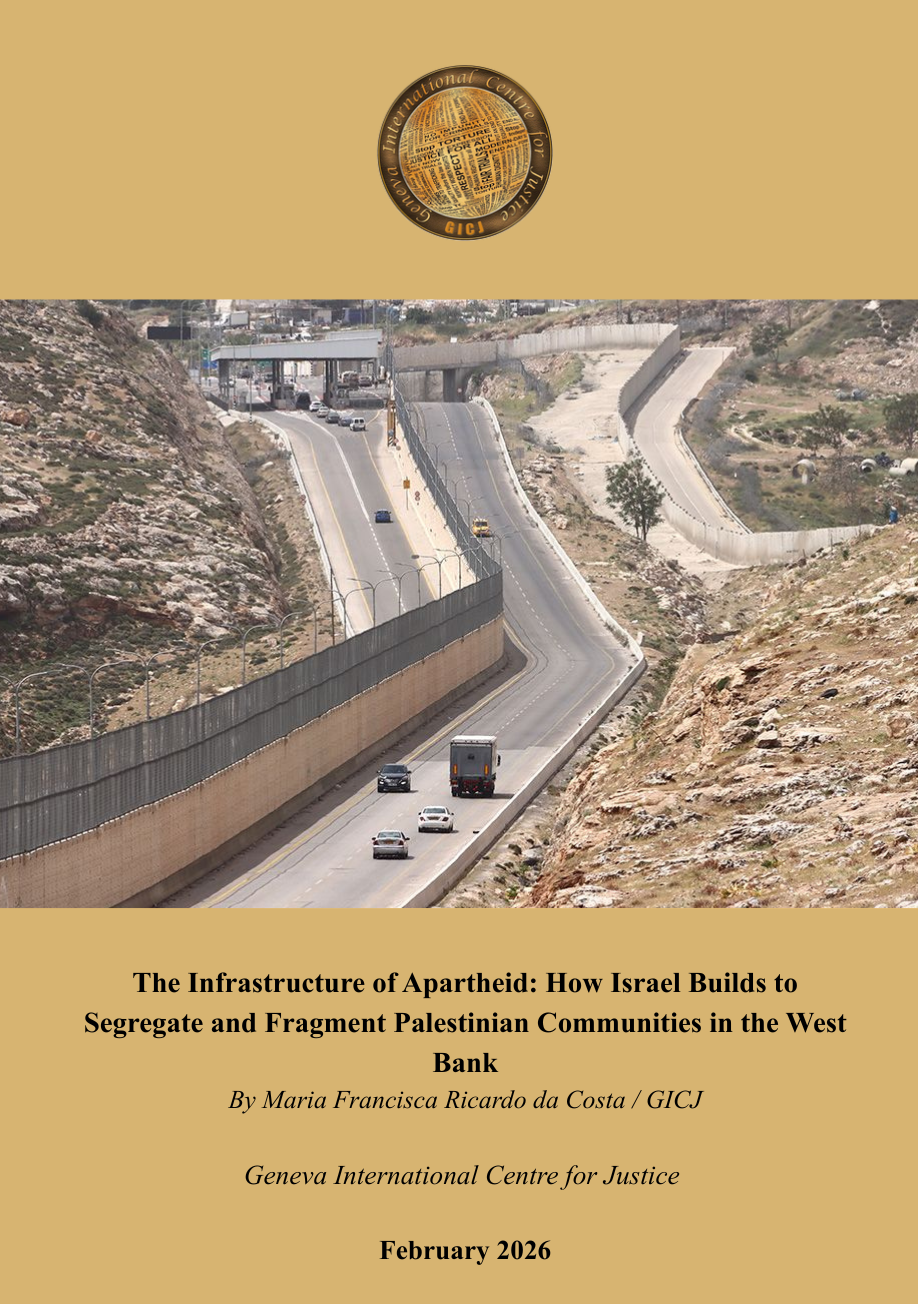

Moreover, throughout the text, references are made only to the situation in Gaza, completely failing to deal with Israel’s violations both in the West Bank and in Jerusalem, which amount to apartheid, illegal settlements and appropriation of land, unlawful killings and beyond.

The deterioration of conditions throughout the entirety of the Occupied Palestinian Territory has been widely recognised by international courts, the UN, and human rights groups. It is evident that no lasting solution for Palestine can be achieved without addressing the problem comprehensively. Israel shall not only withdraw from Gaza and halt its military operations, but it shall also suspend all its illegal settlement activities in the West Bank and respect the international status of Jerusalem.

The plan’s failure to even mention such reality, enshrined once more in international law, stands as a great failure in the process towards peace.

The Question of Aid

Point 7 of the Peace Plan ties aid distribution to the acceptance of the proposed agreement. Once more, conditionality towards humanitarian aid does not have any basis in international law. On the contrary, as an occupying power, Israel is mandated by the 1949 Geneva Conventions to agree to relief schemes and facilitate aid to the occupied population, including food, clothing, bedding and other essential supplies.

The supply of aid is therefore being treated as a bargaining chip in negotiations and is being tied to the acceptance of a peace agreement, in complete disregard of the obligation of Israel to provide the aid expeditiously and thoroughly to the occupied territories, including Gaza.

The Role of the Israeli Occupying Forces (IOF)

In the plan, it is being stated, concretely in point 16, that Israel will not occupy or annex Gaza. Besides being redundant considering Israel’s prohibition to do so in virtue of international obligations and norms, this clause does not seem to be backed by clear security guarantees of non-repetition. The IOF presence in Gaza will not be, according to the text, immediately suspended. Instead, it is vaguely mentioned that the Israeli forces will progressively leave the territory and hand over control to an ad-hoc “international stabilisation force” that will work in cooperation with Israel and Egypt to secure borders. Moreover, an undefined “security perimeter” within Gaza, in which the IOF will continue to be present, is granted until the security situation requires it.

In concrete terms, there is no immediate call for Israel’s full withdrawal from Gaza and no clear benchmark for when that should be concretised. Once more, this stands in unequivocal tension with Palestinian’s right to self-determination and with the Palestinian Authority's pledged reform, embraced by the very text of the deal, which should lead to their control over internal security in Gaza.

The role of the United Nations and Implications for the International Order

As the international community throws itself behind the Trump-backed peace plan, the role envisioned in the deal for the United Nations, the only existing organisation tasked with the duty of maintaining international peace and security, needs to be questioned.

The answer is simple: there is barely any role for the UN.

Aside from the delivery of aid, the United Nation is not being given any sort of involvement in what concerns security guarantees, governance or economic development in Gaza. These prerogatives, that are central to the very core objective of the organisation, are all left to the American-backed international coalitions that do not fall under any existing international mechanism.

In spite of this situation, which threatens to void the deal and undermine any of its legitimacy in the eyes of Palestinians, the United Nations and its members - both officials and states - are openly rooting for the agreement.

Concretely, the UN Secretary General, Antonio Guterres, is calling all parties to commit to a deal that was not the result of multilateral negotiations conducted in the appropriate and legitimate forum, the Security Council, but rather came about as the product of the joint deliberations of two states responsible for the current situation in Palestine.

This endorsement, echoed by Tom Fletcher, Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, generates many doubts as it seems to openly legitimise the behaviour of the United States. The US has blocked numerous multilateral proposals formulated in the UN Security Council over the past months that could have achieved peace earlier, and is instead presenting, almost as an ultimatum, a self-crafted proposal that has not been duly discussed in the Council.

This acceptance from the UN seems all the more absurd considering that on 12 September 2025, the New York Declaration on Israel and Palestine was supported in the UNGA with 142 votes in favour and only 10 against, including those of the US and Israel. The takeaway seems clear: the UN cannot ensure that the will of the international community, in line with relevant resolutions and human rights concerns, is being upheld; while instead it is forced to accept the legitimacy of unilateral, or at best bilateral, deals in resolving intenational crises. Annalena Baerbock, the new president of UNGA, recently stated that “the UN remains the house of diplomacy and dialogue” and that the “test is whether we act”. Once more, the test was failed.

The consequences can thus be widespread and have similar effects on other conflicts happening across the world, marking an erosion that could be fatal for the organisation and for international norms.

Conclusion

The situation in Gaza, and Palestine as a whole, is desperate. Official estimates account for more than 60,000 deaths, many of which are children. Inhumane conditions of life are inflicted on Palestinians, their cities destroyed, and their land shattered into ruins. The IOF continued military operation threatens to deteriorate the situation even further.

Indeed, there is the utmost urgency to terminate the suffering of Palestinians, return prisoners and hostages on both sides and find a solution for lasting peace. However, it should be noted that there are some red lines that shall not be crossed, including in the name of “pragmatism”, such as the question of Palestinian self-determination, security, and respect of their internationally recognised borders as before 1967, which all fall under the broader objective of respecting Palestinian human rights.

This is why Geneva International Centre for Justice (GICJ) calls on the United Nations to take a more proactive stance on the question of Palestine and ensure that any peace deal respects the fundamental rights of both sides, not only one. The inability of the UN, in particular of its Security Council, to agree on a peace plan has resulted in the creation of a strategy that fails to meet international standards and denies Palestinians their rights. We thus urge the UN to do more to present a viable alternative, such as the New York Declaration, and commit to it. We also call on the international community to ensure that Palestinian rights will be upheld and that any deal reflects such reality.