(Photo credits : ©Unicef)

(Photo credits : ©Unicef)

Female Genital Mutilation in West Africa: The Enduring Struggle for Protection and Change

By Haliema Sharfeddine / GICJ

The death of a one month old baby girl in The Gambia on 11 August 2025 after undergoing female genital mutilation (FGM) has sparked grief and outrage across West Africa. The baby, from the Kombo North District near Banjul, was rushed to hospital with severe bleeding but was pronounced dead on arrival. Police later confirmed the arrest of two women suspected of performing the act. The case has reignited debate about the persistence of FGM in the region, despite existing bans and years of advocacy. The incident was widely condemned in national media as a failure to protect children and a reminder of the ongoing struggle against harmful traditional practices. Although FGM has been banned in The Gambia since 2015, enforcement remains weak. A decade after criminalisation, there have been only two prosecutions and one conviction. Rights advocates warn that the practice is increasingly being carried out on infants to avoid detection. Campaigners have warned that families increasingly perform the practice on infants to avoid detection, believing that younger girls heal faster and that such cases are harder to trace.

Background

Female genital mutilation is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons.” It has no health benefits and causes serious and lasting harm, including haemorrhage, infection, infertility, complications in childbirth, and psychological trauma. Globally, over 230 million girls and women alive today have undergone FGM in 30 countries across Africa, the Middle East, and Asia where the practice persists. More than 4 million girls are estimated to be at risk every year, most before the age of 15. WHO warns that FGM is a “severe violation of girls’ rights” and costs health systems about US$1.4 billion annually in related treatment and care. West and Central Africa remain among the regions most affected. According to the UN Population Fund (UNFPA, 2025), 18% of girls aged 15–19 in the region have undergone FGM, and 33% are married before the age of 18. The practice reflects deep-rooted gender inequality and social pressure to conform to community norms around purity, marriageability, and womanhood.

Gambia

The Gambia, one of the smallest countries in West Africa, has been at the heart of both progress and resistance. In March 2024, the country’s parliament voted 42 to 4 to advance a bill seeking to repeal its 2015 ban on FGM, a move that would have made it the first nation in the world to reverse legal protections against the practice. The bill’s sponsor, MP Almameh Gibba, claimed the law violated citizens’ rights to practise their culture and religion. But human rights activists strongly disagreed. Jaha Marie Dukureh, founder of Safe Hands for Girls and a survivor of FGM, told Al Jazeera that such reasoning amounted to justifying abuse. “The people who applaud FGM, many of them are men. They don’t have the lived experiences we do. This is child abuse,” she said. The debate came after the first conviction under the 2015 law in August 2023, when three women were fined for cutting eight infants. Rights groups feared the case had triggered backlash among conservative circles. Equality Now warned that repealing the ban would set a “dangerous precedent” for women’s rights across Africa, risking a rollback of other protections such as child marriage laws.

A Victory for Women’s Rights

In a landmark decision on 15 July 2024, The Gambia’s National Assembly voted to uphold the 2015 ban, rejecting the repeal bill. The vote was widely hailed as a “monumental achievement” by five senior United Nations officials, including Catherine Russell (UNICEF), Natalia Kanem (UNFPA), Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus (WHO), Sima Bahous (UN Women), and Volker Türk (UN Human Rights Office). In a joint statement, they commended the decision as “a reaffirmation of The Gambia’s commitment to human rights, gender equality, and the health and well-being of girls and women.” Deputy UN Secretary-General Amina Mohammed also described the outcome as “a monumental achievement by Gambia for their women and girls.” However, the officials stressed that legislation alone cannot end FGM. With 73% of Gambian women aged 15–49 already cut, most before the age of five, the challenge remains enormous. They urged sustained community engagement, survivor support, and collaboration with traditional and religious leaders to change attitudes and protect future generations.

Regional Overview

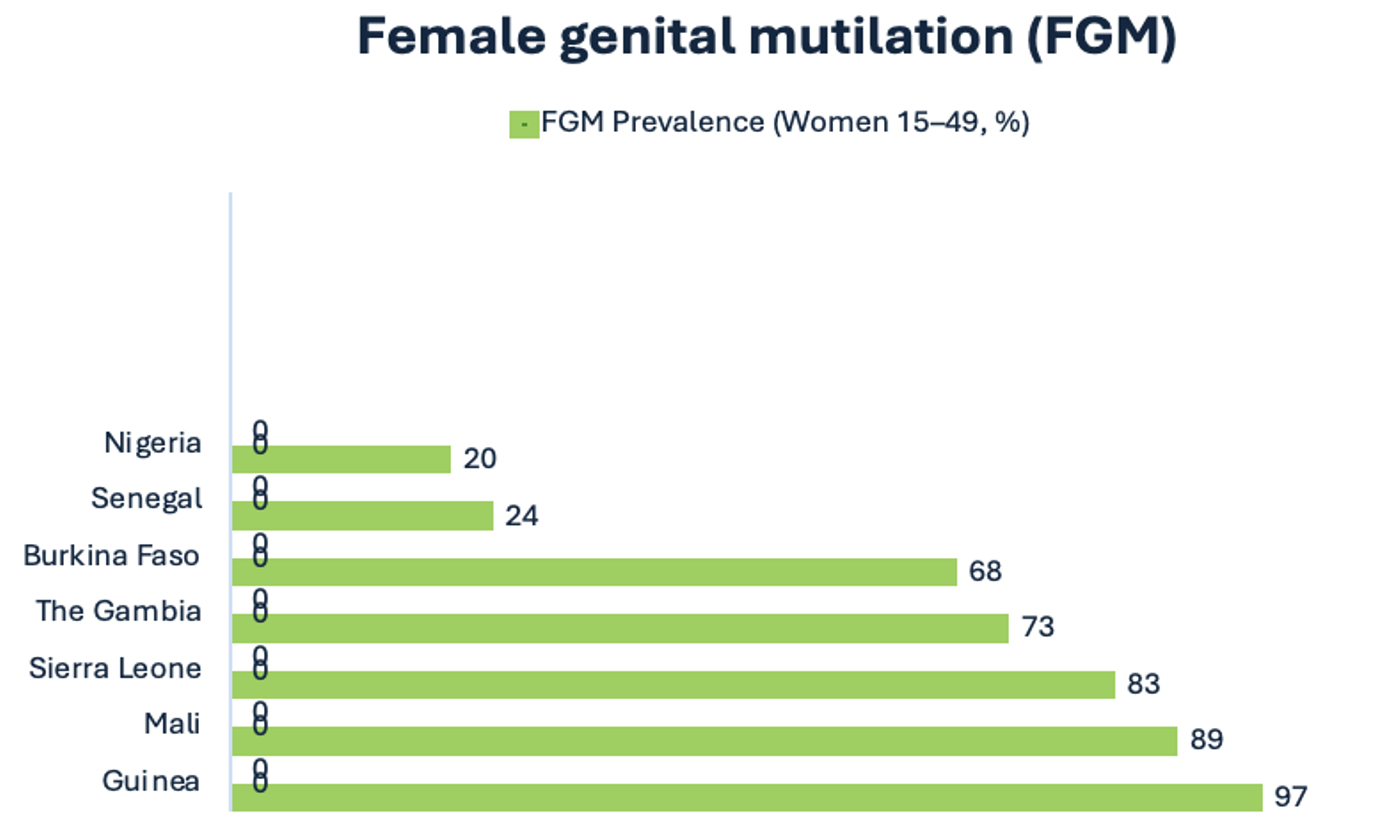

The Gambia’s struggle reflects a wider reality across West Africa, where laws coexist with deep social acceptance of FGM. In Guinea, an estimated 97% of women aged 15–49 have been cut. In Mali, the figure stands at 89%, with no national law banning the practice. In Sierra Leone, 83% of women have undergone FGM, mostly through initiation into the Bondo society. Even in countries where rates are lower, such as Senegal (24%) and Nigeria (20%), FGM remains prevalent in rural and border communities. In many cases, the practice is carried out on infants to evade the reach of law enforcement. The WHO’s 2025 report notes that while global FGM prevalence has declined, the medicalisation of the practice is on the rise. An estimated 52 million women and girls worldwide, one in four of all FGM cases, have been cut by health workers. WHO warns that medicalisation “legitimises violence under the guise of safety” and calls on doctors and nurses to become “agents for change rather than perpetrators.” There are also encouraging signs of progress. Burkina Faso, once among the countries with the highest prevalence, has halved its rate of FGM among girls aged 15–19 in the past three decades. Sierra Leone and Ethiopia have also seen significant reductions, showing that political will and education campaigns can make measurable differences.

Community Voices and Activism

While governments and international organisations play a crucial role, the most transformative work often takes place within communities. Through the UNFPA–UNICEF Joint Programme, more than 20 Gambian communities made public declarations to abandon FGM in 2024. Local civil society groups such as GAMCOTRAP, Safe Hands for Girls, and Women in Leadership and Liberation (WILL) continue to lead grassroots awareness efforts. Amnesty International’s 2025 campaign highlighted activists from across the region. In Sierra Leone, Nancy Gbamoi responds to calls from families reporting gender-based violence and FGM. “When I receive a call about a case, I immediately go to investigate, even at night,” she said. In Burkina Faso, Adama Ouédraogo, a farmer and father of nine, now educates other men about the dangers of FGM, saying, “I have become a contact person in my community because fathers come to me when they face cases of violence against their daughters.” Their stories echo a growing movement that sees FGM not as a women’s issue alone, but as a collective responsibility to protect children and uphold human dignity.

Challenges

Despite legal advances, progress remains fragile. Conflict, displacement, and poverty have worsened vulnerabilities across the Sahel, increasing the risk of girls being subjected to FGM at a younger age. The rise of medicalised cutting further complicates efforts, as families believe it is safer when performed by trained health workers. The UN warns that such beliefs are misguided and dangerous. Even when performed by professionals, FGM causes lifelong harm. Ending the practice requires combining legal enforcement with cultural change, through education, community dialogue, and survivor-led advocacy.

Conclusion

Fourteen years after the world celebrated the beginning of The Gambia’s FGM ban, the country’s reaffirmation of that law stands as a beacon of hope amid persistent challenges across the region. The tragedy of the baby who died in 2025 will be an reminder why vigilance is essential, while the July 2024 parliamentary vote proves that progress is possible through courage and collective action. The Geneva International Centre for Justice (GICJ) commends The Gambia’s decision to uphold its ban on female genital mutilation and calls on all West African governments to strengthen implementation of existing laws, expand education programmes, and ensure medical and psychological support for survivors. FGM is not a cultural expression, it is a violation of human rights. Every girl has the right to life, safety, and dignity. The fight to end this practice continues, but the voices of survivors, activists, and communities show that change is already underway. With sustained commitment, West Africa can move closer to a future where no girl’s life or body is endangered by tradition.