08.12.2017

Table of Contents

- Definition of Genocide

- Prevention of Genocide

- Obligation to Protect Populations

- Background

- The Distinction between Genocide and other Atrocity Crimes

- Response

- Accountability

- The Bloody Trails of Genocide

- Atrocity Crimes yet to be classified as Genocide

- Conclusion

Today, on 9 December 2017, the world marks the International Day of Commemoration and Dignity of the Victims of the Crime of Genocide and of the Prevention of this Crime, established through Resolution A/RES/69/323 that was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in September 2015. The 9th of December was chosen as it is the anniversary of the adoption of the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (the “Genocide Convention”). Marking the third International Day, there is as dire a need as ever to pay attention to warning signs of atrocity crimes and to take immediate action to address them.

Today, on 9 December 2017, the world marks the International Day of Commemoration and Dignity of the Victims of the Crime of Genocide and of the Prevention of this Crime, established through Resolution A/RES/69/323 that was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in September 2015. The 9th of December was chosen as it is the anniversary of the adoption of the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (the “Genocide Convention”). Marking the third International Day, there is as dire a need as ever to pay attention to warning signs of atrocity crimes and to take immediate action to address them.

The Day represents memory and action; memory as vital requirement for action: It carries the purpose of raising awareness of the Genocide Convention and its significance for combating and preventing the crime of genocide and to commemorate and honor its victims. By commemorating past crimes and paying tribute to those perished should strengthen our resolve to prevent atrocity crimes. In unanimously adopting the resolution, the 193-member Assembly reaffirmed the responsibility of each State to protect its populations from genocide, which entails the prevention of such a crime and incitement to it, and that combating impunity for the crime is essential for its prevention.

On occasion of this Day, Geneva International Centre for Justice (GICJ) would like to commemorate the victims of past crimes and draw attention to genocides that have yet to be classified as such. We are gravely concerned that even the most atrocious of crimes against humanity are set aside when confronted with the interests of those great powers that have a stake in the respective region.

Definition of Genocide

Instances of genocide have left bloody footprints throughout history. However, it was not until Lemkin coined the term and the Nuremberg trials employed it in their prosecution of perpetrators that the United Nations established the crime of genocide under international law in the Genocide Convention. Before the term of “genocide” was termed in 1944, “massacre” and “crimes against humanity” were employed to describe intentional and systematic mass killings. The 1941 German invasion of the Soviet Union was described as “crime without a name” by Winston Churchill. “Genocide” was later employed as descriptive term in the indictments at the Nuremberg trials, held from 1945, but was yet to become a legal term.

It was the tragic recognition by the international community that genocide has marred all periods of history that gave impetus for a legal definition. The Genocide Convention (Article 2), adopted on 9 December 1948 by the UN General Assembly through (Resolution 260 (III)) and rendered effective on 12 January 1951, entailed the first legal definition of genocide.

|

It narrowly defines genocide as “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group” – which constitutes the mental element of the crime. The physical element includes the following acts: • Killing members of the group; • Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; • Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; • Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; • Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group. The Convention establishes that genocide, whether committed in the context of peace or international or internal armed conflict, constitutes a crime under international law which parties to the Convention are obliged “to prevent and to punish” (Article 1). The primary responsibility to prevent and stop genocide lies with the State. |

Determining whether intent can be established constitutes a serious challenge. To rule that genocide is being committed, a special intent (dolus specialis) on the part of perpetrators to physically destroy a national, ethnical, racial or religious group must be proven. Cultural destruction or dispersal of a group is insufficient. In case law, State or organizational plan or policy is employed to decipher intent. Moreover, it must be determined that the victims of genocide are deliberately targeted because of their real or perceived membership of one of the aforementioned groups – hence showing that it is the group, not members as individuals, are the target. Genocide also includes atrocious acts against only a part of a given group, provided that this part is identifiable and “substantial”.

Social and political groups, for instance, are excluded – an issue that remains contentious. Critics argue that social and political groups must be considered as target of genocide, owing to the fact that genocide represents a form of one-sided mass killing by a state or other authority aimed at the destruction of a group as defined by the perpetrator. This may well include political opponents of a given regime – as had become manifest under Soviet rule. Some countries such as Ethiopia, France and Spain include political groups as legitimate genocide victims in their legislation.

The internationally recognized definition of genocide of the Convention has been incorporated into the national criminal legislation of many States, and was subsequently adopted by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which established the International Criminal Court (ICC).

Prevention of Genocide

Seeking to decipher the root causes of genocide and genocidal conflicts is crucial for their prevention. As they are not spontaneous acts but develop as process over time, the identification of warning signs is crucial. Identity-related conflicts in contexts of diverse national, racial, ethnic or religious groupings may degenerate into genocide due to their interrelationship with access to power and wealth, resources and services, citizenship, employment and development possibilities, and the enjoyment of fundamental rights and freedoms. Nascent conflicts are fueled by discriminatory practices, hate speech and incitement to violence, and other human rights violations. To prevent escalation, identifying underlying factors such as discrimination in any context that result in or explain acutely disparate treatment of a diverse population, and seeking means to counteract and finally eradicate these factors possibly leading to genocide is vital. In view of the complexity and heterogeneity of societies, genocide is an omnipresent challenge.

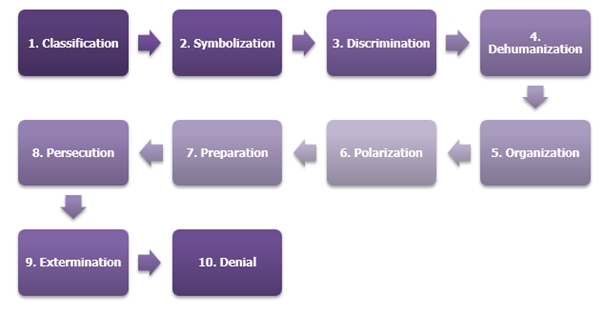

Stages of genocide and its prevention

Economic decline and political confusion and disorganization are arguably central factors in increasing social division, discrimination and violence that may eventually culminate in mass killing and genocide – particularly as they conjure scapegoating of a group for experienced hardship and ideologies identifying a distinct group as enemy. If the manifestation of devaluation of that group throughout history, unresolved conflict and past intense violence with the group, authoritarian political systems and cultures, and inaction on the part of internal and external actors may contribute to the degeneration of a conflict into genocide. To prevent genocide, such factors may be counteracted by e.g. addressing longstanding grievances and root causes of conflict, humanizing the devalued group, fostering ideologies that allow for pluralism.

The graph below shows ten stages in the development of genocide, Dr. Gregory Stanton, which may be used as tools of analysis and prevention with regards to some genocides. However, this framework seems to largely neglect the genocides committed as part of imperial projects.

Preventing genocide must be a national and international priority. It is the only way to avoid the loss of human life, trauma, and long-lasting hardship. Not only does genocide shatter lives, families and societies, it also constitutes threats to international peace and security – as indicated in several UN Security Council resolutions. Therefore, prevention is not only a prerequisite for national peace and stability; it also greatly contributes to a peaceful international arena. In fulfilling their primary responsibility to protect, States reinforce their sovereignty as they reduce the need for intervention on the part of other States or international stakeholders.

|

2005 World Summit Outcome Document: Paragraphs on the Responsibility to Protect 138. Each individual State has the responsibility to protect its populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. This responsibility entails the prevention of such crimes, including their incitement, through appropriate and necessary means. We accept that responsibility and will act in accordance with it. The international community should, as appropriate, encourage and help States to exercise this responsibility and support the United Nations in establishing an early warning capability. 139. The international community, through the United Nations, also has the responsibility to use appropriate diplomatic, humanitarian and other peaceful means, in accordance with Chapters VI and VIII of the Charter, to help protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. In this context, we are prepared to take collective action, in a timely and decisive manner, through the Security Council, in accordance with the Charter, including Chapter VII, on a case-by-case basis and in cooperation with relevant regional organizations as appropriate, should peaceful means be inadequate and national authorities manifestly fail to protect their populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity. We stress the need for the General Assembly to continue consideration of the responsibility to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity and its implications, bearing in mind the principles of the Charter and international law. We also intend to commit ourselves, as necessary and appropriate, to helping States build capacity to protect their populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity and to assisting those which are under stress before crises and conflicts break out. |

Obligation to Protect Populations

Concretizing a political commitment to end the most atrocious forms of violence and persecution, the fundamental need to protect populations must aim at diminishing the gap between States’ fundamental obligations under international humanitarian and human rights law and the reality of populations threatened by genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity. This commitment was fervently debated by the international community and took shape pursuant to the blatant violations committed in the 1990s in the Balkans, Rwanda and Kosovo, as the international community sought to come to terms with its grave failures and discussed possible reaction to gross and systematic human rights violations – which, as Kofi Annan stated, “offend every precept of our common humanity”.

The “responsibility to protect”, then, built on the notions that States have positive responsibilities for their population’s welfare as well as for mutual assistance in case a particular State is either unwilling or unable to fulfil its responsibility to protect or embodies the perpetrator of crimes. The international community would then be obliged to use diplomatic, humanitarian and other means to protect the respective population. Ultimately, the responsibility to protect reinforced sovereignty by supporting States in their fulfillment of existing responsibilities.

The commitment of Member States to protect their populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity, as well as their incitement materialized at the 2005 World Summit. They agreed that in cases when States require assistance to fulfil the responsibility to protect their populations from related crimes, the international community must be ready to assist them and, when States manifestly fail to ensure protection, the international community must be ready to take collective action, in accordance with their UN Charter obligations. The principle also highlights the responsibility of the international community to support States in building capacity to protect their populations and assist those experiencing heightened risks before the outbreak of crises and conflict. Intervention is required only when prevention fails. Prevention was therefore determined as the basis of the principle of the responsibility to protect. However, it has been criticized that these fundamental provisions, which are rooted in international law, including the Genocide Convention, are only followed when hegemonic powers such as the United States and Russia allow for action to be taken. Therefore, when these powers are implicated in atrocity crimes, this “responsibility to protect” does not hold and perpetrators are endowed with impunity – as was evidenced when immunity from prosecution was invoked by the United States following a charge of genocide brought against it by former Yugoslavia following the 1999 Kosovo War.

|

The Outcome Document of the World Summit (A/RES/60/1, para. 138-140) and the Secretary-General's 2009 Report (A/63/677) on Implementing the Responsibility to Protect establish the three pillars of the responsibility to protect outlined above. The Special Advisers on the Prevention of Genocide and on the Responsibility to Protect cooperate with the objective to advance national and international efforts to protect populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity, including their incitement. They are mandated to collect and document information on situations pointing to a risk of these crimes, when factors outlined in the Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes are observed. Given the sensitivity of their mandate, only when the Special Advisers deem the publication of their concerns conducive to the prevention of atrocity crimes in a specific context do they issue public statements or brief the Security Council. |

The term “genocide” was coined by Polish lawyer Raphäel Lemkin in his 1944 book Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. It is composed of the Greek prefix genos, signifying race or tribe, and the Latin suffix cide, meaning killing. Developing the term partly in response to the Nazi systematic murder of Jewish people during the Holocaust and partly in response to previous targeted actions in history geared towards the destruction of particular groups of people, Raphäel Lemkin would later lead the campaign for the recognition of genocide as international crime.

Through Resolution A/RES/96-I of 1946, the General Assembly first defined genocide as crime under international law. In the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (the Genocide Convention), it was codified as independent crime. The International Court of Justice has ruled several times that the Convention embodies principles constituting customary international law, implying that even those States that fail to ratify the Convention as bound by the prohibition of the crime as a peremptory norm of international law (ius cogens) from which no derogation is permitted.

The definition of genocide is equivalent to those in the Genocide Convention and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (Article 6), as well as those in the statutes of other international and hybrid jurisdictions. Genocide is also criminalized in the domestic law in many countries, whereas others are urged to do so.

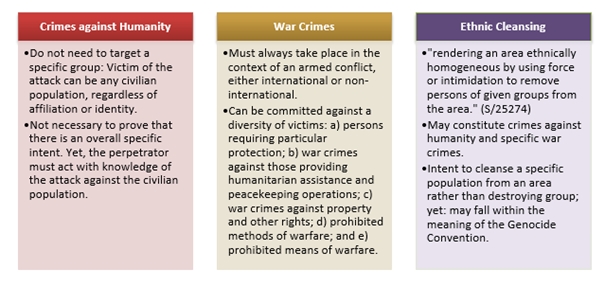

The Distinction between Genocide and other Atrocity Crimes

Response

The horrors of the twentieth century, ravaged by the Holocaust and mass atrocities in Cambodia, Rwanda, Srebrenica and other genocides, revealed the profound failure of States to adhere to their responsibilities and obligations under international law, as well as inadequacies of international institutions. The brutal legacy led the way for provisions for a collective response aimed at protecting populations by preventing escalation of ongoing atrocities or pressing for their termination. When prevention has failed and crimes are ongoing or have been committed, and States “manifestly fail” in their responsibilities, the international community carries the responsibility to take timely and decisive action to protect populations from the atrocities. This may entail collective responses in the form of peaceful means under Chapters VI ad VIII of the UN Charter, or of coercive means, including those foreseen in Chapter VII of the Charter.

While prevention and response may appear to be at opposite ends, they often coalesce: Ending ongoing atrocity crimes should introduce a period of social reconstruction and institution-building aimed at diminishing the risks of a future outbreak of violence. Therefore, response may also serve prevention. Moreover, the international and national obligations to protect carry elements of both prevention and response. An international commission of inquiry to document facts and identify perpetrators as part of the responsibility to protect can also constitute a response. The presence of such a commission in the concerned State can simultaneously contribute to the prevention of further crimes, thus serving as international preventive measure.

Accountability

The relationship between justice and peace is strong. Whereas impunity destroys the social fabric of societies and spreads mistrust among communities or towards the State, thus undermining sustainable peace, accountability for atrocity crimes, if adequately pursued, does not merely serve as deterrent, but can also pave the way for reconciliation and consolidation of peace. The certainty that justice has been served and that perpetrators of atrocity crimes are being held to account helps avert feelings of resentment, bitterness, and desire for revenge of victims, their families, and those sharing ethnic, religious, racial or national origins, which could result in further escalation in violence.

States carry the obligation under international conventional and customary law to ensure accountability for those responsible for acts of genocide and other atrocity crimes and effective remedy for victims. Prosecutions render recognition of the suffering of victims and their families manifest and, alongside other transitional justice mechanisms, help restore some of the dignity or integrity that has been lost or severely damaged.

Knowledge of past crimes, their circumstances and actors should lay the groundwork for the prevention of a recurrence of violence, the establishment of early warning mechanisms, and development of preventive strategies. National and international jurisdiction, the latter of which includes the International Criminal Court and international tribunals or hybrid courts, are essential players in this regard.

International criminal courts and tribunals take on their function primarily as the relevant States are unable or unwilling to prosecute crimes of such magnitude. While all parties to the Genocide Convention are required to prevent and prosecute acts of genocide, this enforcement is obstructed by the additional provision that no claim can be hold against them at the International Court of Justice without their consent, which was signed by some of the signatories – namely Bahrain, Bangladesh, India, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, the United States, Vietnam, Yemen, and former Yugoslavia. This ethically and legally highly questionable immunity from prosecution has repeatedly been invoked, for instance when the US rejected a charge of genocide brought against it by former Yugoslavia following the 1999 Kosovo War.

| As the crime of genocide was not formally defined at the time of the Nuremberg Tribunal (1945-1946), the prosecution of Nazi leaders for involvement in the Holocaust and other mass murders were charged on the basis of already existing international laws, including crimes against humanity. Nonetheless, the term “genocide” was employed in the indictment of Nazi leaders, Count 3, in which it was determined that those charged had “conducted deliberate and systematic genocide – namely, the extermination of racial and national groups – against the civilian populations of certain occupied territories in order to destroy particular races and classes of people, and national, racial or religious groups, particularly Jews, Poles, Gypsies and others”. |

This section provides a non-exhaustive discussion of genocides in history. This necessary focus on some instances of genocide in no way implies that those cases not discussed were not equal in brutality and viciousness.

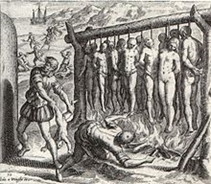

European Colonization

Amidst European colonial expansion in the Americas, Australia, Africa and Asia, massive genocidal violence was carried out against the indigenous populations. It can be argued that colonization in itself is “intrinsically genocidal” (Lemkin). It entailed sweeping obliteration of entire communities and the complete destruction of indigenous peoples’ way of life by colonial powers such as the Spanish and British empires. The indigenous populations’ historical and current territory became occupied by expansion and the formation of States by the colonial regimes, which would impose their way of life on those indigenous groups that survived the slaughters.

Amidst European colonial expansion in the Americas, Australia, Africa and Asia, massive genocidal violence was carried out against the indigenous populations. It can be argued that colonization in itself is “intrinsically genocidal” (Lemkin). It entailed sweeping obliteration of entire communities and the complete destruction of indigenous peoples’ way of life by colonial powers such as the Spanish and British empires. The indigenous populations’ historical and current territory became occupied by expansion and the formation of States by the colonial regimes, which would impose their way of life on those indigenous groups that survived the slaughters.

Imperial and colonial forms of genocide may proceed through the targeted purging of territories of their original inhabitants in an effort to make them exploitable for purposes of colonial settlement or resource extraction, or through the enlistment of indigenous peoples as forced laborers in colonial and imperialist projects of resource extraction (David Maybury-Lewis).

Imperial and colonial forms of genocide may proceed through the targeted purging of territories of their original inhabitants in an effort to make them exploitable for purposes of colonial settlement or resource extraction, or through the enlistment of indigenous peoples as forced laborers in colonial and imperialist projects of resource extraction (David Maybury-Lewis).

Cultural genocide (or ethnocide), which some scholars argue should be included unrecognized in the legal definition of genocide, became part and parcel of these campaigns as those groups that continued to exist were prohibited from exercising their cultural and religious practices and traditions, and were thus robbed of their identities. The treatment of Tibetans by the Chinese state and Native Americans by the US constitute primary examples.

Genocides of the 20th Century

The 20th century bore witness to brutal genocides that would change the course of history, headed by the Jewish Holocaust and other mass killings carried out by Nazi Germany and its allies, mass murders and purges under Communist rule, the Libyan genocide, and the Greek, Assyrian, and Armenian genocides. These genocides, it has been argued, were enabled by the collapse of elite structure and modes of government in many parts of central, eastern and southern Europe pursuant to the First World War, which created fertile ground for Fascism and radical forms of Communism to flourish.

Population transfer and deaths in the Soviet Union

In the Soviet Union, forced population transfer targeted “anti-Soviets” (or “enemies of workers”) and entire national groups, which were then relocated to remote areas. Organized migrations were then conducted to re-populate the ethnically cleansed territories. Around 6 million people are said to have been affected by internal forced migrations, with 1 to 1.5 million estimated to have perished as a result of deportations. Among those deaths, the deportations of Crimean Tatars and Chechens were recognized as genocides by Ukraine and the European Parliament, respectively.

In the Soviet Union, forced population transfer targeted “anti-Soviets” (or “enemies of workers”) and entire national groups, which were then relocated to remote areas. Organized migrations were then conducted to re-populate the ethnically cleansed territories. Around 6 million people are said to have been affected by internal forced migrations, with 1 to 1.5 million estimated to have perished as a result of deportations. Among those deaths, the deportations of Crimean Tatars and Chechens were recognized as genocides by Ukraine and the European Parliament, respectively.

The Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide executed during World War II in which Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany, aided by its collaborators, systematically murdered around six million European Jews, about two-thirds of the Jewish population of Europe. This extermination was carried out by Germany as part of a larger genocidal campaign, culminating in the period from 1941 to 1945, that entailed the persecution and murder of other groups, including Roma, mentally or physically disabled persons, heterosexuals, political opponents, black people, ethnic Poles and other Slavic groups, Soviet citizens and prisoners of war, and Jehovah’s Witnesses.

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide executed during World War II in which Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany, aided by its collaborators, systematically murdered around six million European Jews, about two-thirds of the Jewish population of Europe. This extermination was carried out by Germany as part of a larger genocidal campaign, culminating in the period from 1941 to 1945, that entailed the persecution and murder of other groups, including Roma, mentally or physically disabled persons, heterosexuals, political opponents, black people, ethnic Poles and other Slavic groups, Soviet citizens and prisoners of war, and Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Under the coordination of the SS and with directions from the highest leadership of the Nazi Party, mass murders were committed across Germany and German-occupied Europe, as well as throughout all territories controlled by the Axis powers. The persecution of Jewish Europeans can be divided into several stages: Following Hitler’s seizure of power in 1933, the government adopted laws, notably the Nuremberg Laws (1935), providing for the exclusion of Jews from civil society. Immediately after the rise to power, the Nazis established a vast number of concentration camps in Germany for people deemed “undesirable” and political opponents.

Under the coordination of the SS and with directions from the highest leadership of the Nazi Party, mass murders were committed across Germany and German-occupied Europe, as well as throughout all territories controlled by the Axis powers. The persecution of Jewish Europeans can be divided into several stages: Following Hitler’s seizure of power in 1933, the government adopted laws, notably the Nuremberg Laws (1935), providing for the exclusion of Jews from civil society. Immediately after the rise to power, the Nazis established a vast number of concentration camps in Germany for people deemed “undesirable” and political opponents.

Pursuant to the 1939 invasion of Poland, the Nazi regime erected more than 42,000 segregated ghettos, camps and other detention sites for Jews. From 1941 onward, following Germany’s seizure of territories in the East, the regime escalated its murderous campaign. The deportation of Jews culminated in the policy of extermination, termed the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” by the Nazis. Around two million Jews were murdered in mass executions by paramilitary units within less than a year. Soon, victims were deported from the ghettos in sealed freight trains to extermination camps. Those who had survived the journey were murdered in gas chambers. The genocide was carried on until the end of World War II.

Pursuant to the 1939 invasion of Poland, the Nazi regime erected more than 42,000 segregated ghettos, camps and other detention sites for Jews. From 1941 onward, following Germany’s seizure of territories in the East, the regime escalated its murderous campaign. The deportation of Jews culminated in the policy of extermination, termed the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” by the Nazis. Around two million Jews were murdered in mass executions by paramilitary units within less than a year. Soon, victims were deported from the ghettos in sealed freight trains to extermination camps. Those who had survived the journey were murdered in gas chambers. The genocide was carried on until the end of World War II.

As the world solemnly made its pledge of “never again”, vowing to build societies in which atrocity crimes would not take root and enshrining legal provisions to prevent genocide in the founding documents of the United Nations, it would soon become clear that these efforts were of little avail. Soon, new gruesome waves of atrocity crimes would blaze trails of human misery and cruelty as the international community was standing by and watching. As all too often, power politics, political expediency and voracious self-interest of Member States or sheer mismanagement and weakness blocked effective action – with countless innocent people paying with their lives.

Genocides of the Cold War Era

Thus, despite numerous pledges of “never again” by the international community, genocides continued their bloody path throughout the Cold War Era.

The Cambodian genocide was carried out by the Khmer Rouge regime under the leadership of Pol Pot between 1975 and 1979, leaving an estimated 1.5 to 3 million Cambodians dead. Following the establishment of Democratic Kampuchea by the Khmer Rouge, the regime introduced policies leading to forced population transfer, torture, mass executions, forced labor, malnutrition and disease, which resulted in deaths of around 25 percent (around 2 million people) of the total population.

The Cambodian genocide was carried out by the Khmer Rouge regime under the leadership of Pol Pot between 1975 and 1979, leaving an estimated 1.5 to 3 million Cambodians dead. Following the establishment of Democratic Kampuchea by the Khmer Rouge, the regime introduced policies leading to forced population transfer, torture, mass executions, forced labor, malnutrition and disease, which resulted in deaths of around 25 percent (around 2 million people) of the total population.

In 2001, the Khmer Rouge Tribunal was established by the Cambodian government to try a limited number of KR leadership. With trials beginning in 2009, Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan were convicted for their involvement in the genocide and received life sentences for crimes against humanity in 2014.

The Guatemalan genocide, Mayan genocide, or “Silent Holocaust” describes the massacre of Maya civilians during the Guatemalan military government’s counterinsurgency operations. The atrocious crimes, enshrined in the military regime’s longstanding policy, entailed sweeping massacres, forced disappearances, torture, and summary executions by US-backed security forces. The systematic reign of terror predominantly targeted the indigenous Mayan population, viewed as subhumans and collaborators of the guerillas, through mass killings, the destruction of villages and forced disappearances that had begun around 1975 and peaked in the early 1980s. Around 200,000 Guatemalans were murdered during the Civil War, with 40,000 having been forcibly disappeared. The vast majority of executions (93 percent) were carried out by US-backed government forces. The US-backed Guatemalan army was found to be responsible for the genocide and US training of the officer corps in counterinsurgency techniques was found to have “had a significant bearing on human rights violations” by a UN-sponsored Commission for Historical Clarification in 1999.

The Guatemalan genocide, Mayan genocide, or “Silent Holocaust” describes the massacre of Maya civilians during the Guatemalan military government’s counterinsurgency operations. The atrocious crimes, enshrined in the military regime’s longstanding policy, entailed sweeping massacres, forced disappearances, torture, and summary executions by US-backed security forces. The systematic reign of terror predominantly targeted the indigenous Mayan population, viewed as subhumans and collaborators of the guerillas, through mass killings, the destruction of villages and forced disappearances that had begun around 1975 and peaked in the early 1980s. Around 200,000 Guatemalans were murdered during the Civil War, with 40,000 having been forcibly disappeared. The vast majority of executions (93 percent) were carried out by US-backed government forces. The US-backed Guatemalan army was found to be responsible for the genocide and US training of the officer corps in counterinsurgency techniques was found to have “had a significant bearing on human rights violations” by a UN-sponsored Commission for Historical Clarification in 1999.

The Rwandan genocide, or genocide against the Tutsi, refers to the genocidal mass murder of Tutsi by members of the Hutu majority government during the Rwandan Civil War. Within 100 days, between April 7 and mid-July 1994, an estimated 500,000–1,000,000 Rwandans (70 percent of the Tutsi population) were slaughtered. 30 percent of the Pygmy Batwa also fell victim to the mass killings. Planned by member of the core political elite and high dignitaries of the government, the mass atrocities, including murder, rape as weapon of war, and colossal destruction, were committed by the Rwandan army, government-backed militias, and the Gendarmerie. The genocide came to an end when the Tutsi-backed and heavily armed Rwandan Patriotic Front took control of the country. Around 2 million Rwandans, predominantly Hutus, were displaced or became refugees.

The UN and member states including the US, UK and Belgium, came under heavy criticism due to their inaction and failure to reinforce the UN Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) peacekeepers. France was alleged to have supported the Hutu government after the inception of the genocide.

| Rwanda observed two public holidays to mourn the genocide. Nation-wide mourning begins with the national commemoration (Kwibuka) on April 7, followed by and official week of mourning (Icyunamo) and concludes with Liberation Day on July 4. |

The genocide served as impetus for the establishment of the International Criminal Court to remove the need for ad-hoc tribunals to prosecute atrocity crimes. On 8 November 1994, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) was created by the UN Security Council to prosecute offenses committed during the genocide.

The Bosnian genocide can describe the genocide at Srebrenica and Žepa executed by Bosnian Serb forces in 1995 or the larger ethnic cleansing campaign throughout areas under the control of the Army of the Republika Srpska during the 1992-1995 Bosnian War. Amidst a brutal genocidal crusade against Bosniaks (“Bosnian Muslims”) in Srebrenica in 1995, more than 8,000 Bosniaks (mainly men and boys) were killed and another 25,000–30,000 Bosniak civilians were expelled in and around the town of Srebrenica by Army of the Republika Srpska (VRS) units under the command of General Ratko Mladić.

The ethnic cleansing campaign against Bosniaks and Bosnian Croats across areas controlled by Bosnian Serbs entailed murder, unlawful confinement, torture, rape, sexual assault, beating, looting, and inhumane treatment of civilians; the persecution of political leaders, intellectuals, and professionals; the illegal deportation of civilians; unlawful shelling of civilians and civilian-inhabited areas; appropriation and plunder of property; destruction of homes and businesses; and obliteration of places of worship. While the ethnic cleansing campaign was declared to constitute genocide by the UN General Assembly, German courts and the US Congress, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Court of Justice (ICJ) have ruled that only the Srebrenica massacre meets the legal definition of genocide.

In light of the fatal failure by the UN to prevent the massacre, then Secretary-General Kofi Annan described that, while blame lay “first and foremost with those who planned and carried out the massacre and those who assisted and harboured them”, the UN had “made serious errors of judgement, rooted in a philosophy of impartiality”, depicting Srebrenica as a tragedy that would haunt the history of the UN forever. Several countries, including Serbia and Montenegro and the Netherlands, were found to have failed in their duty to protect. Power politics took their usual turn with Russia, at the request of the Republika Srpska and Serbia, vetoing a UN resolution condemning the Srebrenica massacre as genocide and Serbia describing the resolution as “anti-Serb” in 2015. The European Parliament and the US Congress subsequently adopted resolutions reaffirming the genocidal nature of the crime.

Ongoing Genocides

In spite of the international prohibition of the crime of genocide and legal instruments to punish it, humanity and human dignity continues to crumble in the face of raging genocides that only end once political will on the part of powerful stakeholders permits it.

The Darfur Genocide describes the systematic murder, forced transfer, torture and rape of Darfuri civilians carried out by a group of government-armed and funded militias (Janjaweed) occurring during the ongoing conflict in Western Sudan. Targets of the genocidal crimes, which began in 2003, are the Fur, Masalit and Zaghawa ethnic groups. Darfuri children, women and men are systematically killed and tortured, with their villages being burnt, economic resources looted and water sources polluted. According to UN estimates, the number of those murdered amounts to over 480,000 people, with another 2.8 million people displaced.

The Darfur Genocide describes the systematic murder, forced transfer, torture and rape of Darfuri civilians carried out by a group of government-armed and funded militias (Janjaweed) occurring during the ongoing conflict in Western Sudan. Targets of the genocidal crimes, which began in 2003, are the Fur, Masalit and Zaghawa ethnic groups. Darfuri children, women and men are systematically killed and tortured, with their villages being burnt, economic resources looted and water sources polluted. According to UN estimates, the number of those murdered amounts to over 480,000 people, with another 2.8 million people displaced.

While ISIL has committed atrocity crimes against all civilians living in Iraq, no other group has faced destruction as ferocious as the Yazidis have. More than three years have passed since the beginning of the horrific genocide, as defined by the 1948 Genocide Convention, against the Yazidis by the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL). The genocide has caused forced expulsion and exile of those having survived abductions and massacres from their ancestral lands in Northern Iraq. ISIL’s malicious acts were intended to erase the Yazidis through killing, sexual slavery, enslavement, torture, inhuman and degrading treatment, humiliation, and forcible transfer inflicting serious bodily and mental harm.

Amidst its execution of a systematic campaign of mass atrocities against civilians in northern Iraq in the summer of 2014, ISIL encroached on Sinjar City and other villages and towns in the region predominantly inhabited by Yazidis – who would soon fall victim to unimaginable cruelty and suffering that persist until today. The UN Commission of Inquiry on Syria poignantly described in its June 2016 report that “3 August 2014 would become a dividing line, demarcating when one life ended, and – for those who survived – when another, infinitely more cruel, existence began.”

Amidst its execution of a systematic campaign of mass atrocities against civilians in northern Iraq in the summer of 2014, ISIL encroached on Sinjar City and other villages and towns in the region predominantly inhabited by Yazidis – who would soon fall victim to unimaginable cruelty and suffering that persist until today. The UN Commission of Inquiry on Syria poignantly described in its June 2016 report that “3 August 2014 would become a dividing line, demarcating when one life ended, and – for those who survived – when another, infinitely more cruel, existence began.”

Throughout its brutal genocidal campaign, ISIL systematically separated Yazidi men and women, abducting uncountable Yazidi women and girls into slave markets and employed rape as a weapon of war. They were sold off carrying price tags; married off to ISIL fighters; forced into abortions, sexual mutilation, and sterilization to prevent the birth of Yazidi babies; and constantly subjected to physical and sexual violence such as systematic rape and extreme violence if they resisted or tried to escape. Children were killed in front of their mothers’ eyes as punitive action. Many saw no other escape from the cruel torment than to take their own lives. Captured Yazidi children were forcibly planted in ISIL fighters’ families and training camps, indoctrinated and submitted to military training, and cut off from Yazidi beliefs and practices to erase their Yazidi identities. As Yazidis were fleeing their homeland, they were also separated from their holy city, Lalish, which has been embedded in their religion for centuries that leaving it is a great loss. Many sites of great religious and cultural significance were systematically leveled to the ground. In general, ISIL inflicted conditions of life that brought about a slow death of Yazidis.

and constantly subjected to physical and sexual violence such as systematic rape and extreme violence if they resisted or tried to escape. Children were killed in front of their mothers’ eyes as punitive action. Many saw no other escape from the cruel torment than to take their own lives. Captured Yazidi children were forcibly planted in ISIL fighters’ families and training camps, indoctrinated and submitted to military training, and cut off from Yazidi beliefs and practices to erase their Yazidi identities. As Yazidis were fleeing their homeland, they were also separated from their holy city, Lalish, which has been embedded in their religion for centuries that leaving it is a great loss. Many sites of great religious and cultural significance were systematically leveled to the ground. In general, ISIL inflicted conditions of life that brought about a slow death of Yazidis.

Atrocity Crimes yet to be classified as Genocide

The following section discusses some of those past and ongoing atrocity crimes that are yet to be classified as genocide to pave the way for accountability, justice, and eventual peace. The affected populations are desperately waiting for their suffering to be recognized and for perpetrators to be held to account to regain hope in a future of rights, freedom and dignity for everyone.

Iraq

While ISIS’ gruesome genocidal campaigns against the civilian populations in Iraq and Syria have rightly received ample international attention and elicited urgent calls for investigation and accountability, the atrocity acts by other parties committed amidst the “fight against terror” in Iraq have hitherto been sidelined and their genocidal tendencies neglected.

Under the pretext of fighting ISIS, particularly during their “liberation” campaigns, Iraqi forces alongside pro-governmental militias have committed heinous crimes against civilians on purely sectarian basis, while levelling their cities to the ground. Their campaigns entailed sweeping destruction, looting, and ruthlessness and indiscriminate bombing in civilian-populated and predominantly Sunni areas as well as alarming crimes against uncountable Iraqi families and residents of entire cities, inter alia, enforced disappearances, ill-treatment and physical and psychological torture, and summary executions. Entire families from Sunni communities have been executed.

Under the pretext of fighting ISIS, particularly during their “liberation” campaigns, Iraqi forces alongside pro-governmental militias have committed heinous crimes against civilians on purely sectarian basis, while levelling their cities to the ground. Their campaigns entailed sweeping destruction, looting, and ruthlessness and indiscriminate bombing in civilian-populated and predominantly Sunni areas as well as alarming crimes against uncountable Iraqi families and residents of entire cities, inter alia, enforced disappearances, ill-treatment and physical and psychological torture, and summary executions. Entire families from Sunni communities have been executed.

GICJ has received numerous reports during the campaign that illustrate how people fleeing the city of Saqlawiya and seeking help at the closest military camps instead fell victim to heinous treatment by government-backed militias, which tortured them through beatings and stabbings with knives and other weapons, and abused them psychologically – with verbal abuses containing sectarian connotations.  Moreover, Iraqi police and soldiers actively participated in the executions of innocent people escaping the fighting. Those who survived the massacre reported of civilians being slaughtered, burnt alive, and summarily executed on allegations of affiliations with ISIS. The systematic gross human rights violations committed during the military operations uncover the sectarian nature of the Iraqi government’s campaigns.

Moreover, Iraqi police and soldiers actively participated in the executions of innocent people escaping the fighting. Those who survived the massacre reported of civilians being slaughtered, burnt alive, and summarily executed on allegations of affiliations with ISIS. The systematic gross human rights violations committed during the military operations uncover the sectarian nature of the Iraqi government’s campaigns.

Diyala province, among others, has witnessed well-planned and systematically executed campaigns of forced displacement and killings of people on an ethnic and sectarian basis since the beginning of 2016, in what seems to be a continuation of organized operations with the participation of associated actors operating within Iraq’s current state organs and orchestrated through its branches and units, begun following the US-led invasion in 2003. The heinous crimes were directed intentionally against a specific category of people, namely Sunni Arabs. Hundreds of thousands of members of this particular community were facing death, house demolitions and looting, forced displacement and detention. The burning and desecration of their mosques, in conjunction with the humiliation and insult of their imams and preachers, is strongly indicative of a policy that aims at deliberately degrading the dignity of this specific group.

Hundreds of thousands of members of this particular community were facing death, house demolitions and looting, forced displacement and detention. The burning and desecration of their mosques, in conjunction with the humiliation and insult of their imams and preachers, is strongly indicative of a policy that aims at deliberately degrading the dignity of this specific group.

Iraqi forces and affiliated militias represent a serious threat to the peace and stability in the country and beyond, terrorizing the civilian population, depriving Iraqis of fundamental human rights, and further dividing them along sectarian lines. The abysmal failure by the Iraqi government to protect its citizens is compounded by its unwillingness to conduct appropriate and impartial investigations and ensure reparations for victims.

The recent genocidal crimes are far from being the only ones befalling the Iraqi civilian population; the events that took place in Fallujah during the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq also deserve investigation. The population of this city was subjected to disproportionately heavy shelling by the Coalition. The Coalition-forces have reportedly employed toxic weapons, including large quantities of depleted uranium (prohibited under international law), with the apparent intent to wipe out the city and its citizens. Yet, this intentional crime against the predominantly Sunni population has been largely ignored and its genocidal nature omitted.

Myanmar

While discrimination against the Rohingya minority in Myanmar has persisted in law and in practice throughout the decades, the abuse of the Rohingya community in Myanmar has reached an unprecedented gravity in recent months. The accounts of serious, widespread and systematic human rights violations accompanied by hate rhetoric committed in an organized manner by the Myanmar government, police, security forces and ordinary people against Rohingya based on their ethnic and religious belonging leaves no doubt that committed atrocity crimes amount to genocide as defined by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court and the Genocide Convention, with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, the Rohingya community.

Within the general context of anti-Muslim rhetoric, the Myanmar government and security forces have been perpetuating segregation and persecution policies for decades. Adopted in 1982, the Citizenship Law severely violates the fundamental rights and freedoms of the Rohingya minority, including their freedom of movement and access to lifesaving healthcare, as well as their rights to education and employment. In 2012, the government imposed a curfew that provided fertile ground for exacerbated abuses against the Rohingya. While state and local government authorities impose discriminatory policies, the security forces implement so-called “clearance operations”.

In 2016, the persecution of the Rohingya further escalated, marked by a rise in religious intolerance, especially anti-Muslim sentiment. Incidents of hate speech, incitement to hatred and violence and religious intolerance were rampant. The growing influence of nationalist Buddhist groups and the adoption of discriminatory laws with the objective of “protecting race and religion” by the Parliament between May and August further aggravated the situation.

In 2017, violence against the Rohingya community culminated in atrocious acts carried out in an organized and systematic manner, including extra-judicial and summary executions; rape and other forms of sexual violence; torture and inhuman treatment; largescale forced displacement; seizure, looting and deliberate destruction of housing and livelihoods; and blockages of humanitarian assistance and use of land mines against those desperately fleeing their homes. As the Myanmar government has hitherto failed to adequately address the committed atrocities, and to ensure investigation and accountability of perpetrators, Member States must assume their responsibility under international law to counteract and prevent these acts of genocide.

Palestine

Israel collectively submits Palestinians, regardless of their residency, to an entrenched system of apartheid and institutionalized racial discrimination. Israeli apartheid is anchored in the body of laws instituted after the State’s establishment in 1948. Israel adopted a series of Basic Laws, applied within its own territory and from 1980 onward in occupied East Jerusalem, some which institutionalize discrimination, such as in the field of land policy.

Since 1948, Israel has been in a permanent “state of emergency”, on the basis of which it incorporated the Defense (Emergency) Regulations into its domestic legislation and legal system governing the occupied West Bank. These permit Israeli authorities to conduct, inter alia, innumerable house demolitions, deportations, indefinite administrative detentions, and closures and curfews of Palestinian towns and villages. Further discriminatory laws pertain to entry and residence in Israel and attest to Israel’s policy of demographic engineering, which aims at the maintenance of Israel as Jewish State. While perpetuating the denial and revocation of residency statuses of Palestinians, Israel also continues to carry out deportations and forcible transfers of Palestinians, among them entire communities.

Since 1948, Israel has been in a permanent “state of emergency”, on the basis of which it incorporated the Defense (Emergency) Regulations into its domestic legislation and legal system governing the occupied West Bank. These permit Israeli authorities to conduct, inter alia, innumerable house demolitions, deportations, indefinite administrative detentions, and closures and curfews of Palestinian towns and villages. Further discriminatory laws pertain to entry and residence in Israel and attest to Israel’s policy of demographic engineering, which aims at the maintenance of Israel as Jewish State. While perpetuating the denial and revocation of residency statuses of Palestinians, Israel also continues to carry out deportations and forcible transfers of Palestinians, among them entire communities.

Apart from perpetuating discrimination against Palestinians in all spheres of life and submitting them to unbearable living conditions, the legislative framework combined with geographic fragmentation facilitates inhuman acts, including acts that may amount to genocide. Israel violates Palestinians’ right to life and security of person, particularly through the use of excessive and often lethal force and the failure to hold perpetrators accountable. Israeli forces regularly employ excessive force, including extrajudicial killings, and launch  massive military operations in Gaza disproportionately affecting Palestinian civilians. Israel’s suffocating blockade on Gaza and frequent disproportionate military offensives cause unquantifiable loss and suffering.

massive military operations in Gaza disproportionately affecting Palestinian civilians. Israel’s suffocating blockade on Gaza and frequent disproportionate military offensives cause unquantifiable loss and suffering.

During the 2014 war on Gaza, the Special Advisers of the UN Secretary-General on the Prevention of Genocide and on the Responsibility to Protect expressed their serious concern at the targeting of civilians: “We express shock at the high number of civilians killed and injured in the ongoing Israeli operations in Gaza and at the rocket attacks launched by Hamas and other Palestinian armed groups in Israeli civilian areas.” Moreover, they deplored “the flagrant use of hate speech in the social media” that could dehumanize Palestinians and incite to commit atrocity crimes against them, which is strictly prohibited under international law.

Israel’s recent action to restrict, and, in some cases suspend, electricity to parts of Gaza indicates once again the continuation of an intentional and ongoing Israeli policy aimed at creating conditions of life for Palestinians pointing towards the intention to destroy the Palestinian people, at least in part. In light of this situation, we urge the UN to investigate whether Israel’s action have reached the level of actions—over the better part of a century—that constitute the crime of genocide.

Syria

The Syrian people have borne witness to mass atrocities and cleansing committed by all parties to the conflict, some crimes of which may amount to genocide. In this case, the victim groups are primarily defined in terms of their political opposition to the regime and dominant groups, and may thus be classified as politicide. The Syrian regime has massacred, terrorized, imprisoned, tortured, displaced, besieged and starved tens of thousands of civilians, predominantly political opponents and Sunni Arabs. Such atrocities point towards an intent to destroy these groups “in part”, notably by cleansing the respective group from specific geographic areas. The Secretary-General’s Special Advisor on the Prevention of Genocide, among many other high-level UN officers, has repeatedly expressed grave concerns on the devastating civil war, and has called for an immediate cessation of hostilities and of all human rights violations.

The chemical attacks on rebel-held civilian neighborhoods in in the city of Khan Shikhoun in Southern Idlib and Northern Hama on April 4, 2017, which resulted in an estimated 80 to 100 people dead and more than 500 people injured. The Rahma (Mercy) hospital in Darkush where civilians were taken to be treated – and the last one in the region – was targeted by barrel bombs few hours later.

dead and more than 500 people injured. The Rahma (Mercy) hospital in Darkush where civilians were taken to be treated – and the last one in the region – was targeted by barrel bombs few hours later.

Syrian civilians have been subjected to intensive violence and horrific sieges since the beginning of the armed conflict and Daraya, eastern Aleppo city, al-Waer, Madaya, Kefraya and Foua are witnessing “surrender or starve” tactics by the Syrian government under the so-called “reconciliation” agreements between the Syrian government and armed opposition groups. The government submits the civilian population to brutal campaigns of unlawful killings in densely populated areas, forced displacement and blockages, forcing them to live in inhumane conditions or flee. Employing starvation as a method of warfare, depriving the civilian population of other basic necessities such as water, medicine, fuel, electricity and communications, and blocking access to humanitarian aid have pushed Syrians into immense suffering and death.

Amidst their campaign, the Syrian government and allied militias razed local food supplies by burning agricultural fields in Daraya and Madaya. Syrian government forces committed targeted attacks on civilians, homes, and civilian infrastructure, for instance by shelling Daraya’s only hospital until its collapse. Eastern Aleppo fell victim to horrific and calculated campaigns of unlawful attacks by Syrian and Russian forces, with entire neighborhoods being leveled to the ground indiscriminately. The brutal and relentless shelling aimed at forcing besieged populations to leave their homes.

Tens of thousands of men, women and children have vanished at the hands of the Syrian government, with thousands having died in sinister prisons as a result of subhuman conditions, torture, and disease and countless others withering away. The government has been accused of having organized a crematorium in the notorious Saydnaya military prison to dispose of the remains of thousands of murdered detainees, predominantly political prisoners. While systematic and widespread atrocities against civilians undoubtedly amount to war crimes and crimes against humanity, the government’s intent to destroy the Syrian opposition at least in part must be urgently investigated. Certainly an investigation must encompass the crimes committed by all parties to the conflict, including ISIS, Al-Nusra and armed opposition groups.

Conclusion

On this international day, we need to recognize that the pledge of “never again” must be renewed in all vehemence and must be a principle that overrides the political convenience, opportunism, and greed of those great powers , be they state or non-state actors, that have a stake in the respective region. We need to work concertedly towards protecting individuals and groups from heinous human rights violations and uphold our common humanity.

Preventing genocide and other atrocity crimes is an ongoing process that necessitates tireless efforts to build societies upon the foundations of the rule of law and human rights for all. Their pillars are equality and non-discrimination, legitimate and accountable national institutions, and the development of a strong and pluralistic civil society, among others.

While the primary obligation to prevent atrocity crimes lies with individual States, the international community has the responsibility to act to prevent genocide wherever it occurs if the State in question is unable or unwilling to fulfill its international obligations. In light of this, GICJ calls upon the United Nations and all Member States to spare no efforts in redressing and preventing past and ongoing atrocity crimes, notably in Sudan, Iraq, Myanmar, Palestine and Syria, and to hold all perpetrators to account. In particular, we appeal to those States that have hitherto prioritized immediate economic, military, and political interests over human rights and have therefore been complicit in committed atrocity crimes. We need to stand up together to end genocide where it occurs – not only for the sake of the millions of victims having perished and the countless innocent persons that continue to endure unimaginable suffering, but also for the sake of our common humanity.

|

Read online or download the Report. |

International Days of Remembrance articles by GICJ:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

Prevent Exploitation of the Environment in War and Armed Conflict |

|