by Adrienne Gibbs

Perseverance, Partnership and Progress

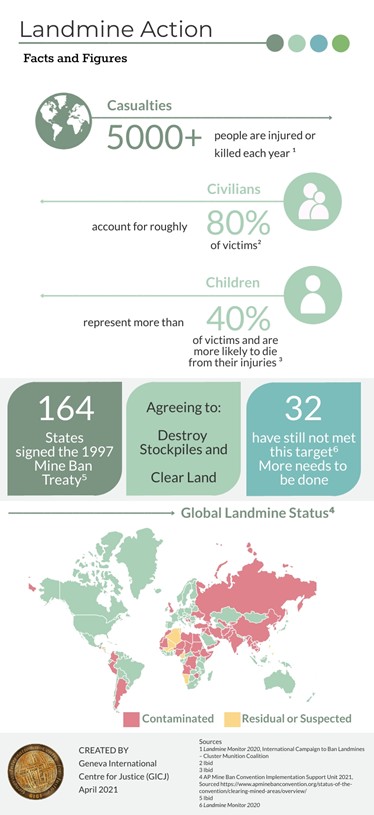

On 8 December 2005, the United Nations General Assembly declared 4 April as International Day for Mine Awareness and Assistance in Mine Action,[1] making a clear statement that the international community needed to do more. In the 15 years since that declaration, significant progress has been made – 164 states are now party to the 1997 Convention on the Prohibition of the use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction (the Mine Ban Treaty), various additional conventions have been signed, global partnerships formed, and most recently, the United Nations Mine Action Strategy was developed. However, despite this progress, more than 5,000 people are still indiscriminately killed or injured by landmines or Explosive Remnants of War (ERW) each year,[2] and many survivors struggle to receive the support and medical assistance they require, demonstrating that there remains much for states and the international community to do.

Extent of the Problem

Antipersonnel landmines are explosive weapons, placed in, under, or on the ground. An effective weapon during conflict, they can remain in place, undetonated for many years. They are usually activated when the victim stands on, or in close proximity to, the mine. Exact numbers of landmines remaining globally are difficult to estimate, but landmines continue to be a persistent issue in at least 66 states.[3]

ERW are unexploded munitions left behind after a conflict and include weapons such as grenades, mortars and cluster munitions. Unexploded munitions, like landmines, can be inadvertently triggered by civilians, causing death and significant injury to those within range.

Landmines and ERW are indiscriminate weapons, killing and injuring men, women and children. In addition, they limit the movement of people and can prevent communities from accessing food, water and other essential service. In conflict zones, their presence can also hinder refugee repatriation and aid efforts.

Not only do landmines pose a grave risk to civilian populations, but also to the brave men and women who undertake peacekeeping missions, deliver aid on the ground, and work to safely clear landmines from affected areas.

Casualties

In 2019, it was reported that more than 2,000 people were killed and over 3,000 injured by landmines or ERW.[4] That means that on average, 13 people a day were impacted, 80% of whom were civilians, almost half were children. The countries most affected in 2019 were Afghanistan, Colombia, Iraq, Mali, Nigeria, Ukraine, and Yemen.[5] The consequences of such incidents on individuals and their local communities cannot be understated. While in many countries, up to 80% of those killed or injured are men and boys,[6] women are also impacted, often over the longer term. As families lose their main source of income, women take on additional financial responsibilities and/or are left to care for those injured or maimed. Rehabilitation and integration can also be difficult, with limited services available and those impacted often facing challenges in social and economic inclusion.[7]

Stockpiling

It is estimated that more than 50 million landmines are still being stockpiled by states including, Russia, Pakistan, India, China, and the United States. Critically, there are still national governments actively laying landmines, most notably Myanmar.[8] And in 2020, the United State changed national laws allowing the defence force to utilize land mines as “necessary warfighting capability” so long as they are equipped with auto destruct or self deactivation safety features.[9] Whilst this sets back progress on anti-landmine action in the United States, it should be noted that to date, the defence force has not made use of this capability. In other states such as Afghanistan, Colombia, India, Libya, Myanmar, and Pakistan, it is reported that non-state armed groups continue to use these weapons to further their interests in national conflicts.[10]

Contamination

Landmines and ERW continue to threaten the lives of civilians even when conflict and fighting has resolved. As noted, 66 states remain contaminated by landmines, 33 of which are party to the Mine Ban Treaty and should have by now cleared the landmines from their lands. 26 countries have indicated they are still contaminated by cluster munition remnants.[11]

Despite reiterating their commitment, capacity and capability issues, financing, and even the COVID-19 pandemic, are leading states to requests continual extensions to their key obligations under the Mine Ban Treaty and other Conventions discussed below.

Collaboration

Disarmament, clearance, and assistance to victims are key pillars in the international response to landmines and ERW. In this regard a number of protocols and conventions have been put in place to encourage and oblige states to eradicate this issue, including:

- The Mine Ban Treaty – signed in 1997 – obliging signatory states to i) cease all use and stockpiling of landmines; ii) clear and destroy landmines and ERW; and iii) provide support to victims. As noted, 164 States are currently party to this agreement.[12]

- Protocol V to the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons, which entered into force in 2006 and is currently ratified by 55 states, deals with the issue of unexploded and abandoned ordonnances. In particular, it calls on states to clear all explosive remnants of war and provide victim assistance.[13]

- The Convention on Cluster Munitions – signed in 2008 – prohibits all use, production, transfer and stockpiling of cluster munitions. In addition, it establishes a framework for victim support, land clearance, risk reduction education and destruction of stockpiles. Notably, 123 states joined convention, committing to destroy stockpiles within eight years and clear land within 10.[14]

- The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities – signed in 2007 – requires states to ensure that victims have access to health care, rehabilitation, employment, social protection and education. A total of 179 States are now party to the Convention.[15]

In addition, the United Nations Mine Action Service was established in 1997 (at the same time as the Mine Ban Treaty) and works closely with other UN agencies including UNICEF, WHO, and UNHCR. In addition to working towards eliminating the threat posed by landmines, the service also undertakes risk awareness education and supports victim assistance initiatives globally.

In 2018, the United Nations Mine Action Strategy was developed outlining the strategic objectives with which the United Nations seeks to address the threat posed by landmines and ERW. It focuses on protecting individuals and communities, supporting victims and their families, and developing national institutions, and is being implemented under a formal monitoring and evaluation process.[16]

Most recently, in 2019, in support of the United Nations Mine Action Strategy, the Safe Ground Campaign was launched with a view to using sport and the sustainable development goals to promote landmine awareness. The Campaign brings together member states, civil society, donors, sporting organizations, and the private sector.[17]

Success and Challenges

The work done by the international community is tremendous and progress has certainly been made. For example:

- In 2019, 123,000 landmines were cleared, with Afghanistan, Cambodia, Croatia, and Iraq making the most progress; [18]

- Before the Mine Ban Treaty, 160milllion landmines were estimated to be stockpiled. Today, that number sits at less than 50 million, with 269,000 destroyed in 2019 alone; [19]

- 99% of the declared stockpile of cluster munitions have now been destroyed;[20] and

- In 2018, mine awareness education was provided to more than 1million vulnerable children globally.[21]

However, despite the significant work and commitments outlined above, according to the Landmine Monitor, donor support has declined in recent years. This is likely to be further exacerbated in 2021 as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. It is difficult to put a cost on removal of landmines, as much depends on the country, the type of terrain, and the techniques used. However, it is clear, that individual states cannot carry the burden alone.

In addition, accesses to services and support for victims and their families remains limited, especially in active conflict zones. For example, in 2019, only six states with cluster munitions causalities had dedicated programs or services in place for victims.[22] Critically, in the 2019 Report of the Secretary-General, Assistance in Mine Action, it was outlined that victim assistance remains the most underfunded pillar of international mine action and victims continue to face significant challenges with regards to social and economic integration.[23]

These are areas where the international community can and should do more.

Geneva International Centre for Justice (GICJ):

- Calls for full and efficient implementation of the Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction (the Mine Ban Treaty) by the states that ratified it.

- Reiterates the importance of universal ratification of the Mine Ban Treaty and urges all states to become signatories.

- Urges states to meet their obligations with regards to destruction of mine stockpiles and clearance of land.

- Encourages the international community, civil society and the private sector to continue and, where possible, increase their collaboration efforts, particularly in the areas of landmine awareness and victim support.

- Continues to report and document human rights violations, including those provoked by the effects of landmines and explosive remnants of war.

[1] United Nations General Assembly Resolution 60/97 2005, sourced: https://undocs.org/A/RES/60/97

[2] International Campaign to Ban Landmines – Cluster Munition Coalition (ICBL-CMC), Landmine Monitor 2020, sourced: http://www.the-monitor.org/media/3168934/LM2020.pdf p17

[3] Landmine Monitor 2020, p17

[4] International Campaign to Ban Landmines – Cluster Munition Coalition (ICBL-CMC), Landmine Monitor 2020, sourced: http://www.the-monitor.org/media/3168934/LM2020.pdf p.17

[5] Ibid

[6] Ibid

[7] Assistance in mine action - Report of the Secretary-General (A/74/288), 10 Sep 2019, sourced https://reliefweb.int/report/world/assistance-mine-action-report-secretary-general-a74288-enar

[8] Landmine Monitor 2020, p.16, 34

[9] Landmine Monitor 2020, p.22

[10] Landmine Monitor 2020, p.16

[11] Landmine Monitor 2020, p.17

[12] Assistance in mine action, 2019 p.3

[13] Ibid

[14] Ibid p.4

[15] Ibid p.4

[16] United Nations Mine Action Strategy 2019-2023, Sourced: https://www.mineaction.org/sites/default/files/publications/un_mine_action_strategy_2019-2023_lr.pdf

[17] UNMAS 2021, Sourced: https://www.mineaction.org/en/safe-ground

[18] Landmine Monitor 2020, p.17

[19] Landmine Monitor 2020, p.17, 34

[20] International Campaign to Ban Landmines – Cluster Munition Coalition (ICBL-CMC), Cluster Munitions Monitor 2020, Sourced http://www.the-monitor.org/en-gb/reports/2020/cluster-munition-monitor-2020.aspx, p.15

[21] Assistance in mine action, 2019 p.8

[22] Ibid

[23] Assistance in mine action, 2019 p.14,17