15.03.2019

By: Roman Kubovic

|

Estonian flag | Photo credit: Fotolia |

|

On 19 and 20 February 2019, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) conducted its third periodic review of Estonia’s human rights situation pertaining to the issues falling under the Committee’s mandate. The review took place within the framework of the Committee’s 65th session in Geneva.

The review began with an overview of the status of economic, social and cultural rights in Estonia by the Head of the Estonian delegation. The delegation Head stressed progress in increasing healthy lifestyles, gender equality and the participation of people with disabilities in the broader society. In addition, he called attention to updates to the criminal code to address issues such as domestic violence and torture.

Following this introduction, the members of the Committee’s Working Group presented their comments on the Estonian National Report and posed a multitude of questions. Areas of concern included the high number of stateless persons in Estonia, relatively high unemployment among minority groups and a wide gender pay gap. In addition, the Committee inquired about a high poverty rate among the elderly population, a high drop-out rate among students and a large gender gap in education. The delegation responded to some of the comments, then offered some final remarks and promised to circulate within 48 hours statistical information on some of the issues raised.

After reviewing all available information, on 8 March 2019 the CESCR issued its Concluding Observations, including recommendations to the State party on how to improve certain aspects of the human rights situation concerning economic, social and cultural rights in the country.

Geneva International Centre for Justice (GICJ) commends Estonia for its positive engagement in the review process and applauds the progress made by Estonia since its last review. However, many issues still face the educational system and there are serious differences in the situations of different ethnic groups in the country. GICJ supports Estonia’s efforts to address these inequalities and all its other efforts to ensure the full enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights by all residents of Estonia.

Third Review of Estonia, 19 February 2019 (Source: GICJ)

Country/Region: Estonia, Europe

Introduction

|

Estonian flag | Photo credit: Fotolia |

|

On 19 and 20 February 2019, the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) conducted its third periodic review of Estonia’s human rights situation pertaining to the issues falling under the Committee’s mandate. The review took place within the framework of the Committee’s 65th session in Palais Wilson in Geneva, the headquarters of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), currently occupied by Michelle Bachelet.

|

The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) is the body of independent experts that monitors implementation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights by its States parties. The Committee was established under the United Nations Economic and Social Council Resolution 1985/17 of 28 May 1985 to carry out the monitoring functions assigned to the ECOSOC in Part IV of the Covenant. All States parties are obliged to submit regular reports to the Committee on how the rights are being implemented. States must report initially within two years of accepting the Covenant and thereafter every five years. The Committee examines each report and addresses its concerns and recommendations to the State party in the form of “concluding observations”. Source: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/CESCR/Pages/CESCRIntro.aspx |

The review began with an opening speech given by the Head of the Estonian delegation. After expressing his gratitude for having the opportunity to participate in his country’s third periodic review by the CESCR, he gave a brief overview of the status of implementation of economic, social and cultural rights in Estonia. Following this introduction, the members of the Committee’s Working Group presented their comments on the Estonian National Report and posed a multitude of questions in four thematic clusters. The Head of the delegation, as well as its other distinguished members from different ministries, had the opportunity to react and to provide information additional to those already incorporated in the report. The delegation then offered some final remarks and promised to circulate statistical information on some of the issues raised within 48 hours.

The Committee subsequently reviewed all the information gathered from the national report, as well as reports obtained from various NGOs and civil society actors, and additional explanations given by the delegation. As a result, on 8 March 2019 the CESCR issued its Concluding Observations, including recommendations to the State party on how to improve certain aspects of the human rights situation concerning economic, social and cultural rights in the country. In accordance with the procedure on follow-up to concluding observations, Estonia is now requested to provide, within 24 months of the adoption of the document, information on the implementation of the recommendations. The State Party is also asked to submit its fourth periodic report, to be prepared in accordance with the reporting guidelines adopted by the Committee in 2008 (E/C.12/2008/2), by 31 March 2024.

Palais Wilson, Headquarters of the OHCHR, Geneva (Source: GICJ)

Below is a summary of Estonia’s third review by the CESCR, including:

• Overview of achievements pertaining to economic, social and cultural rights stemming from the 1966 Covenant;

• Questions relating to art. 1-4 of the Covenant (I. cluster) and responses;

• Questions relating to art. 6-9 of the Covenant (II. cluster) and responses;

• Questions relating to art. 10-12 of the Covenant (III. cluster) and responses;

• Questions relating to art. 13-15 of the Covenant (IV. cluster) and responses;

• Conclusion.

Written documents submitted to the CESCR prior to the review can be found here.

Overview of Achievements

The Republic of Estonia acceded to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights on 21 October 1991 and it entered into force in respect of Estonia on 21 January 1992. This Report covered the period from 2008 to early 2017 and it followed the order of the articles of the Covenant. The Report was prepared by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in cooperation with the Ministry of Education and Research, the Ministry of Culture, the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Communications and the Ministry of Social Affairs. The draft Report was also submitted for consultation to the Chancellor of Justice and relevant non-governmental organisations: the Estonian Institute of Human Rights, the Human Rights Centre and the Legal Information Centre for Human Rights.

To introduce the most notable developments since its last review, the Head of the Estonian delegation underlined the importance of sustainable developments goals (SDGs), in particular Goal 3, Target 3.4, which represented a priority for

| SDG Target 3.4: By 2030, reduce by one third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment and promote mental health and well-being |

Estonia. He informed that the State party has recently been successful in reducing harm caused by irresponsible use and abuse of alcohol and tobacco products, through developing policies and providing counselling to those affected. Estonia has progressed in sharing of family responsibilities between men and women by putting in place measures to reconcile family life with work life, to decrease the gender pay gap amongst men and women, which is still one of the biggest in the EU, and by drafting national plans and strategies to implement gender mainstreaming policies. Thanks to its Welfare Development Plan, the country has now one of the highest employment rates in its history and also one of the highest employment rates among the European countries.

Moreover, the Head of delegation noted that Estonia has adopted multiple amendments to its Penal Code, criminalising human trafficking and aiding of prostitution, punishing domestic violence, torture and other form of ill-treatment. In 2016-2017 the country acceded to the Convention on the Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse (Lanzarote Convention) and Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (Istanbul Convention), both under the aegis of the Council of Europe. In addition, he explained that Estonia offers one of the highest levels of participation in cultural life, social inclusion, availability and accessibility to cultural venues by persons with disabilities, audiobooks and news in sign language for the visually impaired, discounts and other benefits to the disabled, families with children and national minorities. Efforts to reduce the number of persons with undetermined citizenship is always high on the agenda with around 75,000 people being stateless according to the official statistics in 2019.

I. cluster: art. 1-4 Covenant

|

Article 1 1. All peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development. 2. All peoples may, for their own ends, freely dispose of their natural wealth and resources without prejudice to any obligations arising out of international economic co-operation, based upon the principle of mutual benefit, and international law. In no case may a people be deprived of its own means of subsistence. 3. The States Parties to the present Covenant, including those having responsibility for the administration of Non-Self-Governing and Trust Territories, shall promote the realization of the right of self-determination, and shall respect that right, in conformity with the provisions of the Charter of the United Nations. |

Amongst the general questions introduced under Article 1 of the ICESCR were issues relating to justiciability of the rights provided therein. The Committee was interested to know what the domestic remedies for violations of the Covenant’s rights were, whether and how often the Estonian judicial authorities referred to the Covenant as a source of authority, and whether and how they implemented these rights. Furthermore, they inquired about concrete practical examples of cases in which the Estonian courts relied on the Covenant and the rights included therein, and whether Estonia planned to accede to the Optional Protocol to the Covenant (OP-ICESCR), allowing for the individual complaints procedure to be accessible.

The delegation noted that although the Covenant has not been mentioned often in judicial decisions, this did not mean that the judges lacked knowledge thereof. In fact, the Covenant and its contents had been incorporated into Estonian legislation as soon as in 1991. As a result, the courts primarily referred to its domestic laws and to the Constitution, before turning directly to the Covenant. Indeed, there were very few cases in which the courts referred directly to the Covenant or to other international instruments, with the exception of the judgments of the European Court of Human Rights (these are widely cited). Yet, a recent survey has shown that 73% of respondents believed human rights were guaranteed in Estonia. The delegation also provided two concrete examples of cases in which individuals had sought protection in courts of their economic, social and cultural rights, and one example when the Supreme Court had quashed the lower courts’ decisions, referring to general recommendations of the CESCR (especially GC no. 3). As per the status of ratification of the OP-ICESCR, the delegation informed that there have always been discussions on this issue but that they were unable to provide any concrete promises. In a nutshell, the discussions were mainly on the procedural level due to a lack of resources in ministries for the accession to the OP-ICESCR (as an example, the issues of children’s rights were recently on top of the agenda, so the State party took all the measures to adopt all the instruments related to the rights of the child).

|

Article 2 1. Each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes to take steps, individually and through international assistance and co-operation, especially economic and technical, to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights recognized in the present Covenant by all appropriate means, including particularly the adoption of legislative measures. 2. The States Parties to the present Covenant undertake to guarantee that the rights enunciated in the present Covenant will be exercised without discrimination of any kind as to race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. 3. Developing countries, with due regard to human rights and their national economy, may determine to what extent they would guarantee the economic rights recognized in the present Covenant to non-nationals. |

In relation to the obligation of ‘maximum available resources’ the Estonian delegation agreed with the Committee that its social protection expenditure was quite low; in 2016 it represented 16.6% of the GDP. The authorities have put in place strategies to provide public investment in reducing regional disparities in employment schemes, in particular in the Ida-viru county, the most eastern geographical area with a majority of Russian population. The aim thereof was to improve the quality of life and to encourage the business environment in this area. During 2018-2019, several changes took place: new houses were built, new enterprises were opened and a large sum of money was put into tourism section. The Head of the delegation stressed that although the economic status of the non-Estonians in Estonia was lower than that of the Estonians, it was still higher than the general level in other parts of Europe; these differences in economic status were also explained by other factors, such as age, geographical region and others. Additionally, the Committee commended Estonia for ‘going green’ by closing down three oil shale plants; however, the members were concerned about the workers that would lose their jobs and inquired about adaptation policies provided by the State party. The delegation satisfied their concerns by explaining its preparedness to tackle this challenge thanks to the establishment of an unemployment insurance fund, to provide labour market services to the unemployed to help them transition, and also thanks to the EU Commission’s expertise and funding.

On the issue of non-discrimination, the Committee was concerned with the still rather high number of stateless persons in Estonia, ca. 75,000 individuals. The members were interested to know what other

initiatives were in the pipeline in order to expedite and facilitate acquisition of Estonian nationality and whether the State party would consider acceding to the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons and the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. On the latter point, the delegation argued that UNHCR had already recognised that stateless people in Estonia enjoyed the rights provided for in these conventions, indicating that there was no need to formally accede to them. Amongst the measures taken by the authorities to facilitate acquisition of Estonian nationality were: free language courses with a possibility to obtain a paid study leave from work, information on how to acquire the citizenship, simplified procedures for children, and individual approach through counselling. Overall, this issue is a complex one, as explained by the Head of the delegation who took time to inform the members of the Committee in detail of the problems linked to the stateless persons in Estonia. In 1992, the status of one third of the inhabitants had not been determined; thus, it must be born in mind that there has been a decrease from 32% undetermined citizens in 1992 to 5.5% in 2019. The undetermined citizens enjoy, additionally, the same rights as Estonians with the only exception of not being able to participate in public governance. The delegation acknowledged that further efforts must be used to reduce the number of undetermined citizens.

The Committee also inquired about the conditions in which asylum seekers were held and about integration policies and strategies for refugees. Regarding asylum seekers, according to the information provided, a new detention centre was opened in November 2018 (capacity of 123 persons). In addition, there are two accommodation centres (capacity of 70 and 50 persons). In these centres, men and women are placed separately, family members together and unaccompanied minors are offered substitute family services instead of being kept in detention. Health services are provided free of charge, a nurse is present every day, a doctor a few times a week, and a psychologist four times a month. The asylum seekers are entitled to use telephones, Internet, fax, have access to counselling services, a social worker is responsible for organising activities (TV, radio, PlayStation, etc.), and an activity leader provides recreational and cultural activities (cooking, crafts and arts, leisure). In the accommodation centres, people are free to move, they are only obliged to stay during the night. Centres are accessible for people with specific needs. On the other hand, integration of refugees is covered by two strategies: an internal security strategy and the Estonian integration strategy – both are being updated for the period of 2020-2030. A specific body called the ‘Refugee Policy Committee’, composed of representatives from all relevant ministries, meets regularly to discuss the topics, together with NGOs which provide ideas on how to make the services better and how to integrate refugees. Moreover, social workers, support persons, refugees and local municipalities work together in helping the refugees with housing, the state supports them financially in providing the rent (first payment by state, around 1000 EUR per family), and families can apply for subsistence benefits.

|

Article 3 The States Parties to the present Covenant undertake to ensure the equal right of men and women to the enjoyment of all economic, social and cultural rights set forth in the present Covenant. |

According to the delegation, the Estonian authorities have been working tirelessly on decreasing the gender pay gap, and it has been, in fact, steadily happening; yet, not enough. They have been raising awareness, introducing legislative changes and implementing measures, such as the Welfare Development Plan, an amendment to the Gender Equality Act, supporting women in studying IT through online videos, or with the assistance of NGOs working in the sector, and providing trainings and campaigns for gender awareness. However, segregation, education, work experience and other factors only explain around 15% of the gender pay gap. As a result, other analyses are needed to understand where the problem lies.

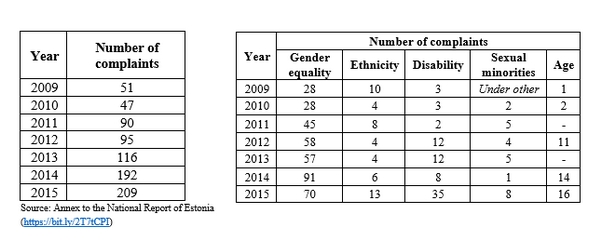

Moreover, the institution of the ‘Gender Equality and Equal Treatment Commissioner’ has been viewed positively; in 2013 there were 116 requests for explanation (cases handled), out of which 61 concerned gender equality issues and in 15 of them an occurrence of discrimination was established. In 2014, the number increased to 192 cases. The Estonian Government increased the budget of this institution from 550,000 EUR in 2015 to 897,000 EUR in 2019. The delegation admitted that more could always be done in terms of funding but at the moment it was sufficient.

II. cluster: art. 6-9 Covenant

|

Article 6 1. The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right to work, which includes the right of everyone to the opportunity to gain his living by work which he freely chooses or accepts, and will take appropriate steps to safeguard this right. 2. The steps to be taken by a State Party to the present Covenant to achieve the full realization of this right shall include technical and vocational guidance and training programmes, policies and techniques to achieve steady economic, social and cultural development and full and productive employment under conditions safeguarding fundamental political and economic freedoms to the individual. |

Under the second cluster of questions the Committee focused on the rights associated with work and rights to social security. With regard to Article 6, the members were mostly interested in updated information on the employment market, nature of employment, employment and unemployment rates in relation to specific minority groups and all the measures taken by the State party to improve the situation. All statistical data was promised to be provided in written form, but there has been positive development from the State’s point of view in terms of decreasing the unemployment rate, especially amongst the non-Estonian population. Salaries have been rising rapidly at a rate of 6-7% per year, as the economy has gone through rapid change. The causes of unemployment are structural; more training for the people is needed and new measures for people at risk of losing their jobs are being introduced. As a result of these policies, more than 4,000 people are taking courses and attending vocational schools. The unemployment rate of non-Estonians was at 7.1% in 2018, compared to 5.4% for the Estonians. The delegation explained that this was also affected by the geographical areas where the people lived (e.g., Ida-viru county), as well as the fact that non-Estonians in the labour market were much older than the Estonians, and, as a result, their health was worse, education had been acquired many years ago and the skills needed in the labour market have changed. To tackle this, the authorities have been working in many different streams at the same time, for example by creating unemployment funds, by providing education, focusing on people at risk and, since 2016, special attention has been given to the disabled.

|

Article 7 The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to the enjoyment of just and favourable conditions of work which ensure, in particular: (a) Remuneration which provides all workers, as a minimum, with: (i) Fair wages and equal remuneration for work of equal value without distinction of any kind, in particular women being guaranteed conditions of work not inferior to those enjoyed by men, with equal pay for equal work; (ii) A decent living for themselves and their families in accordance with the provisions of the present Covenant; (b) Safe and healthy working conditions; (c) Equal opportunity for everyone to be promoted in his employment to an appropriate higher level, subject to no considerations other than those of seniority and competence; (d) Rest, leisure and reasonable limitation of working hours and periodic holidays with pay, as well as remuneration for public holidays. |

The delegation informed that the minimum wage had increased from 278 EUR in 2011 to around 540 EUR in 2019 and the State party, noting that it could always be higher, believed that this sum allowed for adequate standard of living compatible with Article 7 of the Covenant. As the delegation explained, the minimum wage is not decided by the Government; it is negotiated by the trade unions and employers, the Government then merely regulates it, that is to say, transforms the agreement into a regulation, but does not take part in the negotiations. The fact that employers are taxed by the authorities in the same way regardless of whether they pay minimum wage to their employees or not prevents them, in the eyes of the Head of the delegation, from paying their employees below the minimum wage. The gender pay gap has decreased from 29.9% in 2012 to 25.3% in 2016, yet it remains rather high. The State party has been conducting an in-depth analysis to sufficiently address this issue, much research has also been done in relation to employers and how aware they were of the Gender Equality Act, and surveys amongst people to get a clearer understanding of whether they felt discrimination or gender stereotyping, and if things have changed through time. Moreover, the Ministry of Finance conducted an analysis of the gender pay gap in the public sector and sought ways to reduce it; certain amendments to the legislation are waiting to be adopted by the new Government after the elections in March 2019. Furthermore, the authorities have been organising career days for boys and girls, introducing subjects that they normally do not choose due to gender stereotypes, training for gender counsellors, gender mainstreaming training for public servants and raising awareness.

With reference to occupational safety and health, the delegation informed that there were around 6,000 occupational accidents in Estonia per year, which placed the country in the middle of the EU scale. However, the Head of the delegation noted that the increase in the number of occupational accidents was due to the increase in the number of people working, and in the number of accidents reported. The Government is discussing how to mitigate the risks themselves, including possible creation of insurance funds and gathering intelligence on the ways in which employers oversee prevention of accidents in the workplace.

|

Article 8 1. The States Parties to the present Covenant undertake to ensure: (a) The right of everyone to form trade unions and join the trade union of his choice, subject only to the rules of the organization concerned, for the promotion and protection of his economic and social interests. No restrictions may be placed on the exercise of this right other than those prescribed by law and which are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security or public order or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others; (b) The right of trade unions to establish national federations or confederations and the right of the latter to form or join international trade-union organizations; (c) The right of trade unions to function freely subject to no limitations other than those prescribed by law and which are necessary in a democratic society in the interests of national security or public order or for the protection of the rights and freedoms of others; (d) The right to strike, provided that it is exercised in conformity with the laws of the particular country. 2. This article shall not prevent the imposition of lawful restrictions on the exercise of these rights by members of the armed forces or of the police or of the administration of the State. 3. Nothing in this article shall authorize States Parties to the International Labour Organisation Convention of 1948 concerning Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organize to take legislative measures which would prejudice, or apply the law in such a manner as would prejudice, the guarantees provided for in that Convention. |

In terms of trade union rights, the Committee was concerned about the protection of civil servants as they were, according to the Estonian legislation, excluded from the right to strike. The members asked the delegation how public servants might raise their concerns related to the conditions of work and what the rationale behind the restriction was. The delegation shed some light on this by explaining that Art. 59 of Civil Servant Strike Act allowed for collective action, and thus even though strikes were not allowed, up to 49% of civil servants of a particular public authority could use collective action. The rationale behind the restriction placed on the right to strike by public servants was to avoid the closure of important public services. Even though there were different approaches as to how to achieve that, Estonia chose this one as the number of civil servants was very limited, and the authorities have not been able to define which public services were the most important ones. With regard to collective action, there are no limitations on its exercise except one: it must be less than 50% of employees that join it. However, it has never been used in practice. Furthermore, employees are allowed to belong to trade unions, they can turn to the public conciliator of Estonia, or to courts to settle labour disputes. As for the enactment of the draft collective bargaining and collective dispute resolution act, the process was stopped in 2014 as the trade unions and employers did not come to an agreement. However, its previous version from 1993 is still in force and the Government managed to amend some perspectives in smaller parts.

|

Article 9 The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to social security, including social insurance. |

The questions under Article 9 of the Covenant revolved around the sufficiency of the Estonian pension scheme to guarantee adequate standard of living. The Committee was also concerned by the fact that unemployment benefits were not paid in cases were contracts had been terminated at the fault of the employee; this is something that the Committee had recommended to fix during the last review, and they asked for an update. The delegation explained that the average pension was 447 EUR, with a raise of 8.4% expected in April 2019. Although the pension could be higher, it was arguably sufficient for adequate standard of living. On the unemployment benefits, the delegation clarified that there was a difference between unemployment insurance and unemployment allowance. The former is not triggered in cases when termination of contract happens at the fault of an employee; yet, everyone is entitled to the latter as long as certain material conditions are met. The unemployment benefits cover 30% of all the unemployed, the allowance is at 27%, and close to 30% of the unemployed receive a disability allowance. Self-employed persons are not eligible for unemployment benefits but are eligible for unemployment allowance.

III. cluster: art. 10-12 Covenant

Articles 10, 11 and 12 of the ICESCR deal with three principal issues: first, protection of family as the fundamental unit of society which includes questions of assistance to mothers before and after childbirth, education of dependent children and protection of children from abusive child labour; second, the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living, including adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions; and third, the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health.

Under this cluster the Committee sought multiple clarifications. Its members were interested in getting more information about marriage practices and they were concerned with incidents of child marriages of individuals below 14 years of age. The Head of the Estonian delegation shed light on this issue by reiterating several times that there was no practice of child marriage in Estonia. As a principle, the minimum age for individuals to be able to get married is 18 years of age. However, there are reasonable exceptions to the principle, as it is in other countries in the region. The court may, in certain circumstances, allow a marriage of a person of at least 15 years of age. In these circumstances, the law will consider certain persons below 18 years of age as adults by virtue of the Civil Code provisions and upon the court’s approval; child marriage was simply a wrong term. When deciding, the court takes into account the best interests of the child in accordance with the obligations stemming from the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). In recent years there have been two cases where a court allowed it; in both of them, the circumstances were rather special. In the first case mentioned by the delegation, the first instance court had denied the right to marry, yet the circuit (appellate) court overruled it; the permission was granted when the child was already of age. In the second case, a girl of 17 years of age asked to be allowed to marry, the mother agreed, there was no father, the court heard the custodian and decided that she had understood the meaning of marriage. ‘The cases are exceptional and isolated, no general practice exists’, the delegation assured the members of the Committee.

With regard to the issue of domestic violence, the Committee was disturbed by non-existence of specific laws on the subject despite widespread occurrence of the phenomenon. The delegation admitted that no single Act on domestic violence existed in Estonia; however, they argued that the subject matter was regulated in different laws, such as the Criminal Code, Code of Criminal Procedure, Act on the Protection of Victims of Crimes and others. The representative of the Estonian Ministry of Justice clarified that an amendment to the Criminal Code, in force as of 1 January 2015, determined that violent acts committed against a current family member or anybody in close connection would be aggravated offences. Based on qualitative conditions, the authorities are able to distinguish cases of domestic violence from other cases. Amendments to the Penal Code in 2016 criminalised ‘stalking’ and ‘sexual harassment in public or employment situations’. Statistics show that the offences are being reported more, and the increase in numbers is seen in a positive way, indicating that victims and bystanders are more aware of these crimes. This enables law enforcement officers to deal with the cases and helps the social sector to intervene and to provide help.

The Committee maintained that Estonia, as a party to the Istanbul Convention, should enact specific laws on domestic violence, as the phenomenon is the ultimate expression of power imbalance between men and women. The members were not satisfied with high level of gender inequality in Estonia. While commending the authorities for adopting the amendments to the Criminal Code that punish domestic violence, the Committee was sceptical about the reported cases and actual incidents of domestic violence. They inquired further about the statistics and about the manner in which the authorities dealt with the gap. The delegation stated that their last data was from 2014, according to which the police were aware that 60% of cases involved an occurrence of violence; yet, they underlined that this data was from before the amendments to the Criminal Code had been adopted. They admitted that it was a matter that needed further steps and that it would be addressed in the next study on victimology, the results of which the Committee would be informed of accordingly. The members of the delegation added that they have been conducting awareness raising campaigns on domestic violence and on the importance of gender balance and discussing legislation on domestic violence. Women shelter services are now better financed, several new services for victims and for prevention of domestic violence have been put in place, e.g., free service package (psychotherapy, housing, legal counselling) in women shelters, crisis hotline available around the clock.

Another huge issue raised by the Committee under Article 11 of the Covenant concerned the rate of poverty and the right to housing. The absolute poverty rate in Estonia has decreased but the rate of those in danger of poverty is still high, especially among the elderly. In 2018, about 47.5% of persons aged 65 and older lived in relative poverty, while in 2017 it was only 41.2%. This corresponds to relative poverty which results from the fact that the elderly who live alone are at a higher risk; as a result, the authorities focus on this group of people and provide several services, such as free transportation. The Government introduced a few measures in 2018 thanks to which 229 pensioners received financial supplements and 7,900 pensioners living alone received an annual allowance (paid automatically). An additional question concerned an issue of water supplies exceeding permitted limits of fluoride and boron and how the authorities proceeded. As of 2016, 89% of the population is connected to the public water supply whose quality is guaranteed and controlled. Estonia has continuously invested in these measures from the state budget, various EU funds, and local municipalities’ budgets. The amount of fluoride and boron has continued to decrease thanks to several technical measures that the authorities introduced. The final responsibility is to ensure that the quality of drinking water meets set criteria, and this is continuously being checked.

Last issue under this cluster related to the right to health under Article 12 of the Covenant, in particular to widespread problems with alcohol consumption, drug problems and the manner in which it was dealt with by the authorities, rights of drug users, especially women who were pregnant and/or with children, access to medical treatment, HIV/AIDS treatment and stigma, suicide rate and other connected issues.

On alcohol, the representative of the Estonian Ministry of Health confirmed that in 2007 and 2008, Estonia had the highest consumption of alcohol in its history, i.e. 40 litres per capita of absolute alcohol. Yet, in 2017, this number decreased considerably to 10.3 litres per capita. There is hard work behind this decreasing trend, triggered by the 2014 National Alcohol Strategy which the Government has been implementing.

On HIV/AIDS-related issues, the delegation stated that during the last 10 years, the number of newly diagnosed cases decreased by two thirds, while acknowledging it was and would remain high on the agenda in the upcoming years. At the moment, based on their own statistics, Estonia has 7,770 people diagnosed HIV+ (mostly in Ida-viru county and Tallinn). The number is dispersed among those who inject drugs, have many sexual partners, sex workers, homosexuals and prisoners, but it is also increasingly affecting the general public. The state offers free harm reduction/treatment services, access to which does not depend on having health insurance coverage. However, it remains a challenge to reach out to these groups at risk due to stigma. It is important to keep in mind that no quick results in changing stigmatisation can be obtained, it requires systematic work to change. The authorities are going forward with already existing actions but are also looking for new innovative measures to tackle stigmatisation.

On drug use and drug treatment, the authorities work in order to reach out to people through injection and needle programmes, and HIV testing counselling; it is important to increase awareness. Currently, Estonia has 7 opium substitution therapy sites and 37 needle and syringe programme sites in total; as of 2018, they also have two mobile stations. Health services providers who hold licences in psychiatry treat drug problems in Estonia. Treatment and rehabilitation are financed through the National Health Programme from the state budget and services are provided to patients only if they are willing to have these services (no forced treatment) and on an equal basis to drug addicts and HIV+ persons as well as to the rest of the population, female and male. Challenges that the authorities face lie in the number and location of places where services are offered, stigmatisation and finding more special needs for female drug addicts. All these topics are covered in the new National Health Strategy Plan, expected to be adopted by the new Government in March 2019. Starting from 2019, Estonia also has additional resources for HIV/drug addicts’ services, almost 20% more than in previous years. As per the penalties for possession of drugs, criminal sanctions apply in cases where a person has drug doses on himself/herself for ten or more people; otherwise, it is only a misdemeanour. If convicted in criminal proceedings, they must pay procedural costs and undergo examination which they also must pay for. However, the Parliament will soon decide on an amendment to the Criminal Code of two new sections. The amendment would allow, in case somebody has 100 doses on them, but at the same time he/she is an abuser and there are perspectives that it is possible to treat them and they are willing to do so, and agree to it, for the criminal case to be terminated and for the perpetrators to be directed to treatment. Alternatively, in case of repeated criminal activity, perpetrators could be punished by the court under the condition that they will not be sent to jail, but to treatment. There are also grounds for limiting parenting rights of custody: deprivation of the right of custody can only be established by a court order and as a matter of last resort. Custody of a child will not be limited based on the fact that a parent has problems with drug use; it would have to be proven that a parent in a specific case is endangering the child’s well-being.

On suicide rate of 17.7% per 100,000 inhabitants, particularly high among men, the Government conducted a study in 2018, pursuant to which the number of suicides has been decreasing. The authorities now know a bit more about who commits them, and they will deal with the issue.

IV. cluster: art. 13-15 Covenant

Under the last cluster of questions, the Committee discussed the right of everyone to education, including primary, secondary and higher education directed at the full development of the human personality and the sense of its dignity, the right to take part in cultural life, to enjoy the benefits of scientific progress and to benefit from the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author.

The rapporteur commended Estonia for its educational system. However, she enquired about the discrepancy between the decrease in numbers of enrolment in primary education and the increase in numbers of enrolment in secondary education, stemming from data provided by UNESCO in 2016. The delegation clarified that there were technical reasons behind it: the base for calculation in different data sets, compulsory education being closely monitored, in some cases when there are gaps in statistics, this is due to the child having emigrated for instance. Overall, it is ensured that no child is left outside the education framework. Compulsory education starts at the age of 7 but a group of professionals may decide to delay it – this is also not recorded in the statistics (development and readiness of the child considered).

The number of out-of-school children has significantly increased from 257 in 2011 to 5,385 in 2016, the drop-out rate of adults is quite high, in tertiary education there is a large gender disparity in enrolment between men and women, there is a drop-out rate of women due to pregnancy – these are all the issues the Committee raised. The delegation started with some of their own data, they informed that the gender differences in the choice of educational pathways were seen after Grade 9 (continuation of education), there were more men in vocational education and training, drop-out rates were higher than in upper secondary education, women continued in upper secondary general education and then tertiary education. The reasons why boys selected vocational training were complex: performance in basic education, functional skills, possibilities to study in vocational education and training, some pathways were simply more attractive to males – yet the authorities look for possibilities to have a good gender-neutral offer in vocational education. In respect of tertiary education, the number of men is increasing thanks to free tertiary education for all; this reform has had a positive impact on enrolment of men. Root causes are complex and of a social and cultural nature. In order to investigate in depth what should be done, the Government started to develop a new education strategy last year for 2020-2025 in which root causes are focused on. Furthermore, the authorities do not have data on pregnancy as a cause of drop-out. This should not be happening; educational studies may be paused during maternity leave, and this option has been used widely.

The Committee reproached Estonia for being incapable of attracting high quality teachers in mathematics and sciences due to a low social status of teachers. It stressed that raising their salaries back in 2015 had only a modest result and asked if there were any supplementary measures to tackle this problem. The delegation affirmed that it was one of the most crucial issues on their agenda. The authorities monitor the supply/demand of teachers and the choices of teachers in training. Last year a new report was published summing up all the problems and challenges. Very good working conditions must be ensured for teachers and the salary has been a priority for the authorities. In 2019, teacher salaries will be 1,250 EUR, and the forecasted average national salary will be around 1,500 EUR; the aim is for teachers to earn 120% of the average Estonian salary. Teachers are highly valued; the problem is that they themselves see that the support system at school is not enough in their everyday work. The Government addressed that challenge last year and now they have a new system in place as to how to support children with special needs and how to give them the required attention. The state offers free vocational training for people without professional education, and a lot of adults come back to formal education due to career change.

In relation to multiculturalism and to the 2017 CRC’s concern about Estonia’s language policy under which the majority of subjects is taught in Estonian, the delegation informed that the state supports 30 state-funded Sunday schools where people could preserve their language; they support associations and cultural organisations that aim to preserve national identifies; they organise different festivals. Multiculturalism is supported and appreciated in everyday life. The state uses historical names, both in Swedish and in Estonian, in the eastern part of Estonia parallel names (historical) are used. In Narva county, the cities have always been Estonian, and the Government does not aim to change it. Furthermore, in some parts of the country it is possible to communicate in Russian, websites of ministries are in three languages (EE, RU, EN).

The Committee was concerned about the Cultural Autonomies Act which recognises only Swedes and Fins as national minorities (less than 1%), while Estonia has other national/ethnic groups (Ukrainians 2%, Russians 20%). The delegation explained that the situation was historically complex: the Russian group is divided into those who have Estonian citizenship, those who have Russian citizenship and those who are undetermined. However, several organisations deal with this issue. Russian culture is not hindered despite them not having the status of a national minority. The authorities work to balance the preservation of Estonian language while protecting minority cultures and identities through integration - promoting contacts between people, yet giving an opportunity to protect and maintain their national identity; through advertisements, awareness raising and event supporting; and through special cultural programmes protecting cultural heritage, museums, internet portals, and TV channels used by national minorities.

Third Review of Estonia, 20 February 2019 (Source: GICJ)

Conclusion of the Review

The Head of the Estonian delegation expressed his appreciation for the two-day-long open dialogue at the Palais Wilson and his hope to continue this process in the future. He informed the Committee that more clarifying information would be provided in written form within 48 hours in order to have all the questions sufficiently answered. Finally, he expressed his hope to receive the Committee’s report shortly so that its recommendations could be put into practice as soon as possible. The Chair thanked the delegation and the members of the Committee and wished the former a safe return to Estonia. The third review of Estonia by the CESCR was adjourned.

On 8 March 2019, the CESCR issued its ‘Concluding Observations’, including recommendations to the State party on how to improve certain aspects of the human rights situation concerning economic, social and cultural rights in the country. In accordance with the procedure on follow-up to concluding observations, Estonia is now requested to provide, within 24 months of the adoption of the document, information on the implementation of the recommendations. The State Party is also asked to submit its fourth periodic report, to be prepared in accordance with the reporting guidelines adopted by the Committee in 2008 (E/C.12/2008/2), by 31 March 2024.

GICJ Recommendation

Geneva International Centre for Justice (GICJ) commends Estonia for its positive engagement in the review process. GICJ applauds the progress made by Estonia since its last review, including in the area of gender equality. However, more must be done. GICJ notes with concern the many issues still facing the educational system and the serious differences in the situations of different ethnic groups in the country. Ethnicity and gender cannot be used, or allowed to remain due to historical reasons, as a basis for discriminatory actions or outcomes. GICJ supports Estonia’s efforts to address these inequalities through changes in state educational or criminal policy, economic support to groups in need, and all its other efforts to ensure the full enjoyment of economic, social and cultural rights by all residents of Estonia.

![]()

Read online of download the full report.

Justice, Human rights, Geneva, geneva4justice, GICJ, Geneva International Centre For Justice

|

UN Human Rights Council Fortieth Regular Session - GICJ Report |

|

GICJ Reports to the UN Committee on the Eliminaion of Recial Discrimination (CERD) |

|