19.11.2019

A Legal Analysis in the light of International Human Rights Law

Introduction

Israeli settlements are one of the core and most insidious issues in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. Settlements are the most emblematic symbol of the discriminatory system that Palestinian people are facing on an ongoing basis since 1948. They have a devastating impact on Palestinians’ human rights, as well as on their social and economic well-being.

The issue of settlements has received a lot of attention throughout the years by UN bodies, civil society and scholars. A lot of studies have been carried out on the issue of settlements in the light of international humanitarian law (IHL), which is mostly settled law, although the length of the occupation has introduced unique aspects to the situation. However, we note a lack of an updated, comprehensive and systematic review of the legal framework, particularly in regard to specific human rights provisions, applicable to Israeli settlements in the West Bank. Therefore, the major aim of this paper is to outline a review of the relevant international human rights provisions violated by the establishment of Israeli settlements and its associated regime, in order to show that settlements are not just a violation of IHL, but also of human rights law.

Photo: MEMO Photo: MEMO |

Background

In order to undertake a legal analysis, it is preliminarily necessary to outline a clear definition of Israeli settlements, as well as a brief background of the issue in order to frame it in the historical and actual context. Israeli settlements, as communities of Jewish civilians, are a longstanding and growing presence in the West Bank since 1967.

The term “settlement” can be defined as any organized human habitation. In the context of the West Bank, the term “Israeli settlement” refers to civilian communities of Jewish people with Israeli citizenship. The size of these communities can vary from small villages to big towns. They can also take many different forms, such as rural, urban, community and cooperative settlements[1].

Photo: AFP Photo: AFP |

The term is usually used to refer both to those settlements officially recognized by the Israeli Government and legalized under Israeli law and “illegal outposts”, which lack an official Israeli authorization. Both settlements and outposts are considered illegal by the international community under international law.

Ofra settlement in the background and illegal outpost in the West Bank, January 31, 2017. (Photo: AFP/Thomas Coex) Ofra settlement in the background and illegal outpost in the West Bank, January 31, 2017. (Photo: AFP/Thomas Coex) |

Settlements have been built not only inside the West Bank Territory (including East Jerusalem) but also within the Syrian territory[2] in the Golan Heights. Those settlements that had had built in the Gaza Strip where removed in 2005 by a controversial decision of Prime Minister Ariel Sharon[3]. In the West Bank, settlements are mainly located in “Area C”[4], under the full Israeli civil administration and security control; they are partly built on Palestinian private lands.

In order to draw an historical context of Israeli settlements, we have to refer back to the year 1967, when as soon as Israel occupied the West Bank Territory after the Six-day War, the Knesset decided for the establishment of settlements, driven by the strategic concern of establishing a Jewish presence in the Region. The first one that was built was the Kfar Etzion settlement, in the Judean Hills. At the beginning, settlers establishing in the West Bank were driven by a strong ideological mission to re-settle the hills of the ancient Judea and Samaria as biblical holy places.

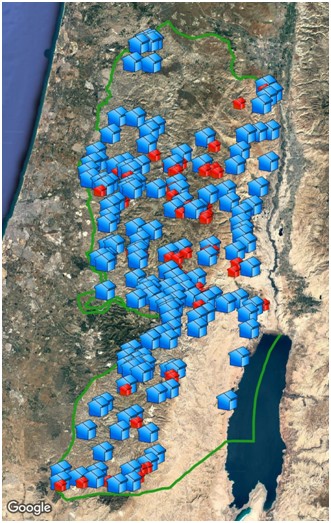

The UN issued the first Resolutions about the legality of settlements in 1979[5], stating that settlements “have no legal validity and constitute a serious obstruction to achieving a lasting peace in the Middle East”. In spite the international condemnation, the number of settlements has grown progressively. By the end of 2017, 132 units of settlements and 106 outposts units were estimated inside the West Bank territory, Jerusalem excluded, with more than four hundred thousand settlers living inside[6]. This means that thirteen percent of the population living in the West Bank is composed of settlers.

Blue = settlements; Red = outposts. (Image: PeaceNow.org) Blue = settlements; Red = outposts. (Image: PeaceNow.org) |

The West Bank is a territory under belligerent occupation since it was captured by Israel during the 1967 Six-Day War[7]. The territory is placed under the authority of the hostile army and the situation is therefore covered by the law of belligerent occupation, which governs the relationship between the occupying power, on the one hand, and the wholly or partially occupied State and its inhabitants, including refugees and stateless persons, on the other[8]. It is therefore subjected to the relevant instruments of International Humanitarian Law, such as the Hague Regulations of 1907 and the Geneva Conventions of 1949.

Israel’s occupation extended over the territory have also seen the establishment of a complex legal and bureaucratic procedure, which implicates the engagement of different bodies and entities, in order to take control of more than fifty percent of the land in the West Bank. This land has been used mainly to establish settlements and create reserves of land for the future expansion of the settlements. The exceptional length of the Occupation of the West Bank is the element that have allowed the impressive growth of Israeli Settlements.

Israeli Settlements Under International Humanitarian Law

A legal analysis about settlements cannot be carried out without tackling the relevant provisions of International Humanitarian Law, especially the law of belligerent occupation[9]. This is the major legal framework applicable to Israeli settlements in the West Bank. International Humanitarian Law is indeed the starting point and the prerequisite of an analysis about Human Rights Law for a comprehensive understanding of the issue. However, IHL’s applicability to Israeli settlements is well-established and undebated and its application to the situation is mostly settled law. Therefore, in this section, we provide just a brief overview of the relevant IHL provisions, without undertaking a deeper legal analysis of subsequent issues.

The international community has repeatedly stated the full applicability of international humanitarian law to the Occupied Palestinian Territories[10]. Israel, the Occupying Power, is bound by international customary law[11] and the Fourth Geneva Convention[12], while the Palestinian population of the Occupied Palestinian Territory is protected by those provisions[13]. Therefore, the Occupying Power bears several obligations, rights and duties under IHL.

Article 49 paragraph 6 of the Fourth Geneva Convention imposes on the Occupying Power the duty of refraining from deporting or transferring parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies. State practice establishes this rule as a norm of customary international law.

Settlements, as communities made by civilians with Israeli citizenship located in the occupied territory, have been established as part of a national policy. The Government have been funding their construction and luring and encouraging the migration to settlements while providing financial incentives; the Government is investing proportionally more public money into the settlement communities than it does in mainland Israeli communities. Settlements not only constitute a cheaper alternative for those that cannot afford the cost of living of other places in Israel, through subsidized housing and mortgages programs[14], but also have a lot to offer in term of services. Schools in the settlements receive better funding than mainland schools, in the form of higher salary for teachers, scholarship advantages and other educational benefits. The Government support allows a very high quality of life in settlements and try to keep the ordinary life in settlements as much normal and liveable as possible. This policy clearly involves the transfer of a civilian population into the territory occupied by Israel. It therefore constitutes a breach of article 49 paragraph 6 of the Fourth Geneva Convention.

Photo: Amir Cohen/ REUTERS Photo: Amir Cohen/ REUTERS |

Under International Humanitarian Law, namely article 49 paragraph 1, the individual or mass forcible transfer and deportation of protected persons within or outside the occupied territory is also prohibited.

Since 1967, Israel has been expelling and displacing whole communities of Palestinians for the purpose of establishing settlements, throughout the West Bank[15]. A specific example is the policy adopted in East Jerusalem, were almost half of the demolition operations take place, aimed at evicting the Palestinian population remained in the area[16]. Just between January and May 2019 more than 311 Palestinians were displaced throughout Areas A, B C and East Jerusalem.

The ruins of Lifta, a Palestinian village near Jerusalem, from where Palestinians were forced to leave. (Photo: Ester Inbar) The ruins of Lifta, a Palestinian village near Jerusalem, from where Palestinians were forced to leave. (Photo: Ester Inbar) |

In addition, Israel bears specific duties in regard to private and public properties located in the occupied territory. IHL prohibits the destruction of real or personal property belonging individually or collectively to private persons, or to the State, or to other public authorities, or to social or co-operative organizations[17]. The rule is part of customary international law[18] and it might also constitute a war crime in international armed conflicts[19]. An exception exists for those situations where such destruction is rendered absolutely necessary by military operations. The Occupying Power is also limited in regard to the use of such properties, since it has to act only as “administrator and usufructuary” of public properties and safeguard them[20]. Regarding private properties, the occupying power has a duty to respect and not confiscate them[21].

Israel carries out the demolition of Palestinians’ structures, often to the advantage of the establishment, development and maintenance of settlements and without any military necessity[22]. Demolished structures may be residential, livelihood-related, service-related or part of infrastructure. The demolitions usually are carried out by Israeli authorities but in these cases the owners are forced to do so by the authorities.

Israel has consistently been confiscating Palestinians properties to the advantage of Israeli settlements[23]. Since the Occupation started in 1967, more than 49,320 structures have been demolished in Palestine, and, just between January and May 2019, 213 Palestinian owned structures were demolished or seized[24].

Palestinians looking at Israeli forces demolishing homes in Hebron, Occupied West Bank. (Photo: APAImages) Palestinians looking at Israeli forces demolishing homes in Hebron, Occupied West Bank. (Photo: APAImages) |

Finally, IHL also prohibits the exploitation of natural resources of the Occupied Territory in order to derive from them an economic benefit. Israel has been economically exploiting West Bank’s natural resources such as land, water and sea. Throughout the West Bank, Israeli quarry companies extract approximately 17 million tons of stone annually, almost all of which is destined for the Israeli local market[25]. Israel has permitted mining concessions to ten Israeli-operated quarries in Area C of the West Bank and approximately 94% of the production – which yields stone, gravel and gypsum – is shipped to Israel for construction and infrastructure purposes. These West Bank operations make up between 20%-30% of Israel’s annual quarrying requirements, with royalties paid to the State of Israel[26]. Israel is also exploiting the Dead Sea for the extraction of its mineral resources for the development of profitable cosmetic industries and raw materials[27].

Photo: Conscious Voyager Photo: Conscious Voyager |

Several provisions of IHL apply to the issue under our analysis, prohibiting specific acts and policies perpetrated by an occupying power in the context of occupation. The Israeli policy of establishing settlements has involved extended land grabs as well as the displacement and forcible eviction of the local population and other actions that contravene several provisions of the Fourth Geneva Convention. Even though the application of these provisions is undebatable and has been well acknowledged by the international community, those violations have consistently been perpetrated by Israel against Palestinians. The following section will now explore the less-discussed issue of Israeli settlements under International Human Rights Law.

Israeli Settlements Under International Human Rights Law

The applicable law

In order to elaborate an analysis of the relevant provisions of International Human Rights Law that are applicable to the Occupied Palestinian Territory, it is first of all necessary to establish which is the law applicable within the context under our consideration.

Human Rights Law, as a body of international law, applies not only to the territory of a State’s sovereignty but also over those territories where the State exercises effective control and over those citizens that are within the State’s jurisdiction. Human rights law applies at all times to all people, including during a situation of military occupation and is therefore not compromised by the applicability of international humanitarian law[28].

The West Bank is considered by the international community and customary international law to be an Occupied Territory[29], where Israel exercises its effective control. Israel, the Occupying Power, has been exerting its authority over the territories consistently since 1967.

Israel’s obligation under international human rights law, applies both to the territory of Israel’s sovereignty and to those territories on which Israel exercises effective control, such as the Occupied Palestinian territories[30]. Israel bears the duty to respect, implement and fulfil the human rights of Palestinian people living under its control. Specifically, the human rights treaties ratified by Israel are applicable in respect of any acts done by Israel in the exercise of its jurisdiction outside its own territory, such as the establishment of settlements. Israel ratified the following human rights core instruments:

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR)

- International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD)

- Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC)

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD)

Therefore, Israeli settlements will be considered in the following analysis in the light of customary international human rights law and those human rights treaties that have been ratified by Israel.

The right to equality and non-discrimination

Human rights law lays down rights, principles and obligations that States are bound to respect; the right to equality and freedom from discrimination constitutes one of the fundamental human rights principle[31].

The term “discrimination” should be understood to include any distinction, exclusion, restriction or preference which is based on any ground and which has the purpose or effect of nullifying or impairing the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by all persons, on an equal footing, of all rights and freedoms[32].

The rights to equality and non-discrimination is stated in several Treaty provisions, such as article 2, paragraph 1, of the ICCPR, which imposes on States the duty to respect and ensure to all persons within their territory and subject to their jurisdiction the rights recognized in the Covenant without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. In addition, article 26 of ICCPR recognizes that all persons are equal before the law and entitled of an equal protection of the law; it also prohibits any discrimination under the law and guarantees to all persons equal and effective protection against discrimination on any ground such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. In similar terms, article 2, paragraph 2, of the ICESCR and article 2 of the CRC prohibits any kind of discrimination based on any ground. In regard to racial discrimination, the CERD as one of the key non-discrimination treaties, develops provisions in order to eradicate intolerance and discrimination based on race, colour, descendent, national and ethnic origin.

The rights of equality and non-discrimination, as a principle with a general character, assumes relevance in relation to the implementation of other human rights.

The right to equality and non-discrimination is significant within the context of Israeli settlements. Among those people that are living in the same territory, the West Bank occupied by Israel, only one group is restricted in the access and enjoyment of several rights. This unequal treatment takes place in different and many ways[33] and the discriminatory actions perpetrated by Israel are grounded on racial, religious, ethnic and national factors.

Photo: Getty Image Photo: Getty Image |

More broadly, there is an evident discriminatory policy carried out at the national level against Palestinians and the discrimination measures to which they are subjected are worsened by their alleged purpose: expelling a particular ethnic group from certain territories occupied by Israel and establishing an institutionalized segregation regime. In this respect, many scholars and other experts have argued that Israel’s discriminatory system of segregation against Palestinians constitutes the crime of Apartheid according to the Rome Statute. They found reasonable grounds of the fact that Israel is committing inhumane acts in the context of an institutionalised regime of systematic oppression and domination, enforced by one racial group over another racial group, with the intention of maintaining that regime[34].

As a result, it is clear that Israeli settlements, as currently managed and ruled by Israel, lead to violations of the right to equality and non-discrimination of Palestinian people.

Right to Property

The individual right to property is recognized in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights under article 17, stating that “No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property”.

Although the right to property is extremely controversial in its formulation and was not included in the ICESCR and ICCPR, primarily due to the inability of governments to agree on a common formulation, it is touched on in article 15 and 16 of CEDAW, in article 5 of CERD, and article 15 of the CMW[35], as well as in several Regional Human Rights Treaties.

Despite persisting controversies, the right to property is widely recognized as a universal human right: indeed, property is what grounds other rights and enables the individual to act as a free agent, and it is needed not just to realize other human rights but also to preserve human dignity[36]. The inalienable human right to property should therefore be understood as a negative obligation consisting of a protection against arbitrary dispossession. That the right to property is not just a legal right but is intrinsically recognized as a universal human right clearly attested by several international and regional human rights instruments, as well as numerous national constitutions[37]. In regard to the right to property, the UN General Assembly[38] has emphasized its particular significance in fostering widespread enjoyment of other basic human rights and its contribution to the development of individual liberty and initiative. It has also called for further measures to protect the right to everyone to own property through the adoption of domestic legal provisions against the arbitrary deprivation of one's property.

As specified, the right to property includes the right to be secure from arbitrary expropriation of property, which means that the State cannot remove ownership arbitrarily. The “arbitrary nature” of an expropriation comes from the fact that it is not for a public purpose, it is not carried out in the framework of consistent legal standards, does not take place under due process of law, does not provide fair compensation, or is done in a discriminatory way[39]. Expropriation can also take place through measures having an equivalent effect, namely indirect expropriations[40].

Israeli settlements and outposts are often established on Palestinians’ private properties that have been seized from their legitimate owners. Settlers are often making use of private houses that have been grabbed from Palestinians.

Photo: AFP Photo: AFP |

-

The Absentees’ Property Law

The legal mechanism that has been used by Israel in order to confiscate Palestinian properties for its own use is the Absentees’ Property Law. Under the law, “property” includes immovable and movable property, moneys, a vested or contingent right in property, goodwill and any right in a body of persons or in its management. The law states that the properties of any absentee[41] will be taken and transferred to the control of the Custodian for guardianship until a political solution for the refugee problem was reached. Although a theoretical possibility was recognized for absentees to acquire the property back after confiscation, this was impracticable in the majority of the cases[42]. The Absentee Property Law has also been used over the years as a tool by Israeli settler associations for the takeover of Palestinian owned properties in East Jerusalem[43].

First of all, the implementation of this law has resulted in the de facto expropriation of Palestinian properties. In practise, it denies an owner the ability to use or sell property or otherwise heavily encumber its use. Secondly, the law is guided by an unlawful discriminatory principle: it does not apply to the properties of settlers in the West Bank but exclusively to the properties of Palestinians.

For these reasons, the legal instrument tackled above has to be considered as an arbitrary means of expropriation since it has the effect of expropriating private properties without assuring a fair compensation, without a process for the owner to reclaim the property and applying a discriminatory standard.

-

The Regulation Law

The Judea and Samaria Settlement Regulation Law (Regulation Law) was passed by the Israeli Knesset on 6 February 2017. It purports to retroactively legalize Israeli settlements built in the Palestinian territories on private Palestinian land.

The law concerned some 4000 settlers’ houses and was meant to "regulate" the status of those residences, proving that they have been built “in good faith” or with “government support”. The law states that title to the land on which the residences are built will remain with the legal owners, but the usage will be expropriated by the State, therefore allowing settlers to remain in their homes. Under the law, Palestinian landowners were offered monetary compensation for the long-term use of their property or, when possible, an alternative plot of land. Palestinians will not be able to reclaim it “until there is a diplomatic resolution of the status of the territories”.

Jewish settlers standing in front of illegal Amona outpost. (Photo: Debbie Hill/UPI) Jewish settlers standing in front of illegal Amona outpost. (Photo: Debbie Hill/UPI) |

Even if the law clarifies that title to the land will remain with the Palestinian owner, it causes an effective restriction that infringe upon the right to property, since it results in the seizure and prevention of use. The practical effect is the legalization of a land confiscation that has not been carried out according to the international protection of the right to property.

Immediately after it was passed, the law was challenged by a group of Israeli and Palestinians NGOs, advocating that it is unconstitutional. The petitioners requested the Israeli High Court to issue an interim injunction, which would prevent the implementation of the land expropriation processes until a final decision by the Court is issued. The law was also opposed by the Israel’s Attorney General Avichai Mandelblit who declined to defend the Regularization Law in Court, calling it unconstitutional and against international principles, namely IHL and the right to property [44]. The proceeding is still pending while the implementation of the law has been temporarily blocked by the High Court.

If the law discussed above successfully passed the examination of the High Court of Israel and was applied in the future, it would lead to the expropriation of Palestinian land in a way that would violate the human right to property. Indeed, even assuming that Israel does have the authority to expropriate those properties, the way the expropriation is carried out by Israel does not meet the international standard established in order to protect from arbitrary seizure of properties because it is a discriminatory measure applied without a public purpose and a consistent legal standard.

The Israeli settlement of Maale Adumim as seen from East Jerusalem. (Photo: Thomas Coex/AFP/Getty Images) The Israeli settlement of Maale Adumim as seen from East Jerusalem. (Photo: Thomas Coex/AFP/Getty Images) |

Right to an adequate standard of living

The right to an adequate standard of living is a fundamental human right requiring that everyone shall enjoy basic needs such as nutrition, clothing, housing, medical care and social services. Everybody should be able to enjoy these needs in conditions of dignity and without obstacles.

-

Right to housing

The right to adequate housing is a core component of the right to an adequate standard of living and is enshrined in many international human rights instruments[45]. The human right to adequate housing is the right of every woman, man, youth and child to have a safe and secure home and community in which to live in peace and dignity.

The obligation to respect the right to adequate housing means that Governments must refrain from carrying out or otherwise advocating the forced or arbitrary eviction of persons and groups. States must respect people's rights to build their own houses and order their environments in a manner which most effectively suits their culture, skills, needs and wishes.

Israel’s policy related to house construction, specifically in East Jerusalem is linked with the establishment of Jewish settlements. Israel has the practise of ordering the eviction of Palestinians from their houses in order to replace them with settlers[46], of demolishing Palestinian houses in order to build houses for settlers and of denying of building permits to Palestinians in order to maintain the “Jewishness” of an area.

Photo: AP Photo/Dan Balilty Photo: AP Photo/Dan Balilty |

As a consequence, these policies result in the denial of security of housing to Palestinians, since those who are evicted from their houses would be likely to face again the same situation if they located elsewhere. Therefore, those policies openly violate the right to adequate housing as intended above.

-

Right to water

The right to water, although not explicitly mentioned in the UDHR, has been considered implicitly part of the right to an adequate standard of living under the ICESCR since it is one of the most essential conditions for survival[47]. It has been recognized as a universal human right[48] with legal foundations in other human rights treaties as well[49].

The right to water is indispensable for leading a life in human dignity. The human right to water entitles everyone to sufficient, safe, acceptable, physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic usage[50]. The right of water includes the right to a system of water supply and management that provides equality of opportunity for people to enjoy the right to water. Water and water facilities have to be accessible to everyone without discrimination, within the jurisdiction of the State party.

In the context of OPT, water and other natural resources have been seized from Palestinians in order to be allocated to Israeli settlers. The Military Orders issued in 1967 and currently in force transferred authority over water resources in the OPT to the Israeli military and prohibited Palestinians from constructing new water installations without a military permit. These orders only apply to Palestinians and not to Israeli settlers. While all Israeli settlements are connected with the Mekorot national water system and receive developed-world levels of water for drinking, sanitation and commercial use, more than 150 Palestinian communities lack any connection to a water network and have no other choice than to rely on shallow wells or purchase water from tankers at a considerable price[51]. In addition, some Israeli settlements have taken control of Palestinian water springs in the West Bank with the assistance of the Israeli military, therefore impeding access by Palestinians.

Palestinian children fill plastic gallons with drinking water from a vendor in Khan Younis. (Photo: AP) Palestinian children fill plastic gallons with drinking water from a vendor in Khan Younis. (Photo: AP) |

As a result, settlers enjoy unlimited access to running water year-round and Israel created world-class hydro technology for the creation and export of desalination plants, advanced irrigation systems and the recovery and productive recycling of wastewater[52] while Palestinians face water insecurity and shortages. Therefore, settlements directly violate the right to water of Palestinians, since they prevent them from having access to adequate quality or supply of water. Not only that, they have also played a prominent role in perpetuating discrimination in the West Bank. The different regimes that apply to settlers and Palestinians in the access to water violates the right to non-discrimination and the right to an equitable access to fundamental human right. This is just an example of the extreme environmental discrimination system in Palestine that has also been called “environmental apartheid” arising from the occupation.

The pool of a B&B inside Nofei Prat Jewish settlement in the West Bank. (Photo: UPI) The pool of a B&B inside Nofei Prat Jewish settlement in the West Bank. (Photo: UPI) |

-

Right to food

The right to food is the right to have regular, permanent and unrestricted access, either directly or by means of financial purchases, to quantitatively and qualitatively adequate and sufficient food corresponding to the cultural traditions of the people to which the consumer belongs, and which ensure a physical and mental, individual and collective, fulfilling and dignified life free of fear[53].

The right is enshrined in several instruments under international law, most relevantly in the ICESCR, which deals more comprehensively than any other instrument with this right, stating that “the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions”. Article 11.2 recognizes that more immediate and urgent steps may be needed to ensure “the fundamental right to freedom from hunger and malnutrition”. The human right to adequate food is of crucial importance for the enjoyment of all rights[54].

Food insecurity is a major issue in the Occupied Palestinian Territories and is directly related to and compounded by the absence of food sovereignty, caused by the segregation regime imposed by the occupation. Palestinian land that was in the past used for farming has been confiscated and the restriction of movement due to the establishment of settlements, walls, checkpoints and separate roads have affected the ability of Palestinians to carry out farming activities.

The absence of a direct control over water resources by Palestinians has had negative implications over the ability to develop farming techniques and irrigation technologies. This not only increases food insecurity but also undermines the main business of the Palestinian economy.

Therefore, Israel’s policy over land and resource confiscation, such as the establishment and expansion of settlements and the infrastructure built to support them, is the major cause of food insecurity and violation of right to food in the West Bank.

Israeli settlement of Beitar Illit. (Photo: Menahem Kahana/AFP) Israeli settlement of Beitar Illit. (Photo: Menahem Kahana/AFP) |

Right to self-determination

The right to self-determination is the principle of international law providing that all people have the right to establish their own political system and internal order, to freely pursue their own economic, social and cultural development, and to use their natural resources as they deem fit.

The right is enshrined in the UN Charter[55] and in different human rights treaties, such as ICCPR art 1.1 and ICESCR art 1.1. The Palestinians’ inalienable, permanent and unqualified right to self-determination has been recognized by several UN Resolutions and the International Court of Justice.

Settlements have had the practical effect of dividing up and fragmenting the West Bank territory, affecting the demographic composition of the territory. By the end of 2017, 132 units of settlements and 106 outposts units were estimated inside the West Bank territory, Jerusalem excluded, with more than four hundred thousand settlers living inside[56]. This means that thirteen percent of the population living in the West Bank is composed of settlers. In addition, settlements have led to a lack of sovereignty over natural resources, such as land and water, as described above.

Through the establishment of settlements, Israel has consistently denied Palestinians the ability to exercise the right to self-determination. Indeed, the government policy of establishing settlements makes it extremely difficult or impossible for the right to self-determination to be exercised, an outcome that appears to be the very intent of Israel’s settlement policies.

The right of people and nations to permanent sovereignty is a basic constituent of the right to self-determination over their natural wealth and resources must be exercised in the interest of their national development and of the well-being of the people of the State concerned[57]. Among the natural resources belonging to a population, one of the most important is land.

Although the right to land is not considered in itself as a universal and specific human right according to international human rights law, several instruments link land issues to the enjoyment of specific substantive human rights[58]. Land is therefore necessary in order to achieve other human rights. Indeed, land is for many people an essential source of livelihood which is central to economic rights. It is also linked to peoples’ identities and so is tied to social and cultural rights.

The access to, the use of and the control over land directly affect the enjoyment of a wide range of human rights that in the case of Palestinians are denied on discriminatory grounds. The ICERD refers to land while providing that States[59] must be committed to prohibit and eliminate racial discrimination in all its forms. It affirms the right of everyone, without discrimination, to own property alone as well as in association with others, to inherit and to housing.

Land has always been a central element in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. Land was the prerequisite and the territorial basis of the Jewish State envisioned by the Zionist movement. In 1948, displaced Palestinians lost millions of dunams[60] of land and the majority of this land was captured by Israel through force, whether through expulsion or blocking the return of those who fled[61]. The seizure was then followed by a process aimed at legally transforming the status of these lands.

Land also serves as the physical basis of each new settlement and for the Jewish colonization in the West Bank. In the case of Israeli settlements, portion of lands are captured from Palestinians in order to be allocated for the use of people belonging to the Jewish community. The dispossession of Palestinian lands for the establishment of a new settlement, takes place through different means, among those, the declaration of private land as abandoned property[62] and the requisition for military or public needs. The main technique currently used by Israel in order to seize Palestinian private land is declaring those areas as “State land”. By appealing to the Ottoman law[63], Israel started to declare as “State land” all the lands that were not registered and not cultivated. The whole system of land expropriation has been facilitated by a lack of a comprehensive property registration system. This is a consistent national policy carried out by Israel.

Given these facts, it is evident that there is discrimination against the Palestinian national group involving a distinction, exclusion, restriction and preference in regard to allocation of lands. This policy has the intention of impairing the enjoyment, on an equal footing, of the right to land.

Settlements, as shown throughout the paper, result in private land takings and in the deprivation of the occupied population’s right to freely dispose of its natural wealth and resources. The right to natural resources sovereignty is violated by the establishment of Israeli settlements and its associated discriminatory policies.

Conclusion

The establishment of Israeli settlements and its associated regime constitute a violation of numerous aspects of international law, including both international humanitarian law and international human rights law. While the violations of IHL have been well documented, this paper has focused on examining how settlements violate human rights law. Unfortunately, the human rights law violations are numerous and varied.

The right to equality and non-discrimination is openly violated by Israeli applying different standards and granting different rights to people living within the West Bank territory. The right to own property is violated by the establishment of settlements on Palestinians’ private properties that have been illegally expropriated from their legitimate owners. The denial of the right to an adequate standard of living, which includes the right to housing, water and food, is another consequence of the establishment of settlements. Palestinians are also deprived of direct control over their natural resources and safety of housing. Finally, settlements, which have had the practical effect of fragmenting the West Bank territory and changing the demographic composition of the territory, have made it extremely complicated for the right to self-determination to be exercised by Palestinians.

A protester waves a Palestinian flag in front of the Israeli West Bank settlement of Beitar Illit on 5 September 2014 during a demonstration against Israel’s decision to expropriate 400 hectares of land in the territory. (Photo: Musa Al Shaer/AFP) A protester waves a Palestinian flag in front of the Israeli West Bank settlement of Beitar Illit on 5 September 2014 during a demonstration against Israel’s decision to expropriate 400 hectares of land in the territory. (Photo: Musa Al Shaer/AFP) |

GICJ Position

GICJ stresses that Israeli settlements are illegal under both international humanitarian law and international human rights law. A prompt response is needed from the whole international community. States must engage themselves personally in order to bring to an end the unacceptable breaches of international law committed by Israel through its settlement regime and the associated apartheid system.

[1] Throughout the remainder of the paper the term “settlements” will be used to refer to both settlements and outposts since the legality of them under Israeli law does not affect considerations made in the light of human rights law and IHL.

[2] The Syrian Golan is a region in southwest Syria which was occupied on June 5, 1967 by Israeli forces and subsequently annexed on December 14, 1981 by Israel. The move has been recognized by the international community (Security Council Resolution 497, 1981) as “null and void”.

[3] A as consequent of the Israeli disengagement from Gaza, 9,480 Jewish settlers were expelled from 21 settlements in Gaza.

[4] The Occupied Palestinian Territories were divided by the Oslo II Accord into three administrative divisions with different status: Areas A, B and C. Area A is exclusively administered by the Palestinian Authority; Area B is under Palestinian civil control and joint Israeli-Palestinian security control; Area C, which contains the Israeli settlements, is subjected to the full Israeli civil and security control. Although the division was made to be temporary and the control gradually shifted to the Palestinian Authority, “Area C”, which constitutes 60 percent of the occupied West Bank, is until now under full Israeli control.

[5] Security Council Resolution 446 (1979)

[6] Peace Now: http://peacenow.org.il/en/settlements-watch/settlements-data/population.

[7] This has been recognized by the international community. The International Court of Justice in its Advisory Opinion stated: “The territories situated between the Green Line and the former eastern boundary of Palestine under the Mandate were occupied by Israel in 1967 during the armed conflict between Israel and Jordan. Under customary international law, these were therefore occupied territories in which Israel had the status of occupying Power. Subsequent events in these territories have done nothing to alter this situation. All these territories (including East Jerusalem) remain occupied territories and Israel has continued to have the status of occupying Power.”

[8] Int’l Comm. of the Red Cross, The Law of Armed Conflict: Belligerent Occupation (June 2002), https://www.icrc.org/en/doc/assets/files/other/law9_final.pdf.

[9] Belligerent occupation is regarded as a component of an international armed conflict.

[10] A/HRC/34/38.

[11] Including The Hague Regulations.

[12] Israel ratified the Fourth Geneva Convention in 1951.

[13] Art. 27 of the 1949 Geneva Convention IV.

[14] https://www.dw.com/en/israel-lures-settlers-with-financial-incentives/a-16487892.

[15] Those acts may also amount to a war crime according to the Rome Statute.

[16] https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/palestinians-battle-home-evictions-east-jerusalem-silwan-181206052617178.html.

[17] Art. 53 of the 1949 Geneva Convention IV.

[18] International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Customary IHL Database, Rule 50.

[19] Article 8(2)(a)(iv) of the Rome Statute.

[20] Art. 55 of the 1907 Hague Regulations.

[21] International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) Customary IHL Database, Rule 51, codified in article 46 of the Hague Regulations.

[22] https://www.ochaopt.org/theme/destruction-of-property.

[23] https://imemc.org/article/p-a-denounces-israels-confiscation-of-522-dunams-of-palestinian-lands-in-southern-west-bank/.

[24] Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Data on Demolitions and Displacementin the West Bank, UN, https://www.ochaopt.org/data/demolition.

[25] Yesh Din, The Great Drain: Israeli Quarries in the West Bank (Sep. 2017).

[26] A/HRC/40/73 - Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967

[27] The Dead Sea partly lies within the Occupied Palestinian Territory but is off-limits to any Palestinian development.

[28] International Court of Justice, Advisory Opinion, para. 112.

[29] International Court of Justice, Advisory Opinion, para. 78.

[30] A/HRC/34/38.

[31] On the question of non-discrimination, see General Comment No. 18 of the Human Rights Committee in UN doc. HRI/GEN/1/Rev.5, Compilation of General Comments and General Recommendations adopted by Human Rights Treaty Bodies.

[32] General Comment No. 18 of the Human Rights Committee in UN doc. HRI/GEN/1/Rev.5, Compilation of General Comments and General Recommendations adopted by Human Rights Treaty Bodies.

[33] The following sections will discuss several specific subject areas showing how Israel is acting with a discriminatory intent, therefore harming Palestinians’ rights.

[34] According to the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), the investigation and the possible prosecution of the crime is under the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court, which is currently conducting a preliminary examination of the crimes committed in all parts of the territory of the State of Palestine.

[35] Alson, International Human Rights 282.

[36] Rhoda E. Howard-Hassmann, Reconsidering the Right to Own Property, 12 Journal of Human Rights 180, 183 (2013).

[37] Christophe Golay & Ioana Cismas, Legal Opinion: The Right to Property from a Human Rights Perspective (2010).

[38] Resolution A/RES/43/123.

[39] Freya Baetens, Expropriation in International Investment Law, Oxford Bibliographies (23 Aug. 2017), https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199796953/obo-9780199796953-0159.xml.

[40] Indirect expropriations take place when the Authority exerts a de facto and effective control over a property, or when it seriously interferes with its use and enjoyment, even without a formal expropriation.

[41] The definition of “absentee” is broad and unclear. It encompasses anyone who at any time after 29 November 1947 has been living in or was a national of an enemy country or is a Palestinian Refugee who fled or was expelled from their ordinary place.

[42] Norwegian Refugee Council, Legal Memo: The Absentee Property Law and its Application to East Jerusalem (Feb. 2017), https://www.nrc.no/globalassets/pdf/legal-opinions/absentee_law_memo.pdf.

[43] Id.

[44] Therefore, the government was forced to hire a private attorney in order to defend it.

[45] Such as article 11.1 of ICESCR.

[46] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/01/israel-evicting-palestinian-family-replace-settlers-190115061242614.html.

[47] CESCR, General Comment No. 15: The Right to Water (Arts. 11 and 12 of the Covenant).

[48] “The human right to safe and drinking water and sanitation is derived from the right to an adequate standard of living and inextricably related to the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health, as well as the right to life and human dignity.” HRC Res. 15/9 (30 Sep. 2010).

[49] Article 14, paragraph 2 (h), Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women; article 24, paragraph 2 (c), Convention on the Rights of the Child.

[50] UN Doc. E/C.12/2002/11 (2002).

[51] B’Tselem, Water Crisis (2017).

[52] A/HRC/40/73 - Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, p. 12.

[53] Special Rapporteur on the right to food: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/Food/Pages/FoodIndex.aspx.

[54] General Comment 12, Twentieth session, E/C.12/1999/5 (12 May 1999).

[55] Articles 1 and 55.

[56] Peace Now: http://peacenow.org.il/en/settlements-watch/settlements-data/population.

[57] General Assembly resolution 1803 (XVII) of 14 December 1962, "Permanent sovereignty over natural resources".

[58] https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/Land_HR-StandardsApplications.pdf.

[59] Article 5(d)(v)–(vi) and (e)(iii) of ICERD.

[60] The term “dunam” refers to the Ottoman unit of area: one dunam is 1,000 square metres (10,764 sq ft), which is 1 decare.

[61] Geremy Forman & Alexandre Kedar. From Arab Land to ‘Israel Lands’: The Legal Dispossession of the Palestinians Displaced by Israel in the Wake of 1948, 22 Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 809 (2004).

[62] Under the Absentee Property Law (1967).

[63] The Ottoman Lands Law of 1858, applying in the territory at the time of application, defined different types of lands: matrouk was the land used for public purposes, such as roads; miri was the land belonging to the Sultan; mawat was the so called “dead land”, not in possession of anyone which is a state’s property, although it might be cultivated. Matrouk, miri and mawat constituted State Land according to Israel’s interpretation. Tomis Kapitan, Philosophical Perspectives on the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict (2015).