By Lisa-Marlen Gronemeier

Literacy is a tool of empowerment, of development and positive change on an individual and collective basis. It is an enabling factor in encouraging people to claim their rights and bring about change in their social, political, and economic environment. With the aim of highlighting the importance of literacy and adult learning to individuals, communities and societies globally, UNESCO designated September 8 International Literacy Day in 14 C/Resolution 1.441 in 1966.

Literacy is at the core of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 – which aims to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” – but is also essential to achieving the other SDGs. Owing to the transformative capacities of education, it is at the heart of UNESCO’s mission to build peace, fight poverty, and foster sustainable development. Mandated to cover all aspects of education and sustaining a worldwide network of specialized institutes and offices, UNESCO is entrusted to work towards achieving this goal with its partners through the Education 2030 Framework for Action (FFA).

This year, International Literacy Day is held across the world under the theme of “Literacy in a digital world”. UNESCO particularly aims at examining what literacy skills people need to stand their ground in increasingly digitally-mediated societies and how they can reap the opportunities that the digital world holds.

Our world today continues to be ravaged by conflict. On the occasion of this day, Geneva International Centre for Justice (GICJ) would like to call attention to the detrimental impact of armed conflict on literacy and education, particularly by shedding light on the situations in Iraq and Syria – two countries whose literacy rates and educational systems have fallen victim to war. Subsequently, the importance of digital literacy in contexts of armed conflict is discussed.

The State of Literacy

Although literacy rates have steadily risen over the past decades, at least 758 million adults and 263 million out-of-school children around the world are illiterate, predominantly women and girls. This reveals the road that lies ahead of working intrepidly towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially Target 4.6 to ensure that all youth and most adults attain literacy and numeracy by 2030. One major obstacle blocking the road to literacy is conflict. The devastating conflicts being waged in our times have caused significant disruptions in the literacy of tens of thousands of children – which may have extremely detrimental consequences for their individual development and prospects as well as for the stability, peace, and sustainable development of their countries.

The meaning of literacy is changing in a world in which digital technologies are entering every aspect of our lives: the way we live, work, learn, access information, and communicate. While the rapid technological development entails many opportunities, those who lack access to digital technologies and the required literacy – the knowledge and competencies to navigate them – run risk of being left behind and becoming marginalized. This is particularly dangerous in contexts of armed conflict.

Early Literacy as Key to Fluency

Early attainment of literacy is imperative for lifelong reading fluency, according to education specialist Helen Abadzi. Students who have not attained reading automaticity by age 19 show “adult neo-literate dyslexia” – which implies that they have long-lasting difficulties reading and comprehending texts1. They may thus pass by store signs and street names without being able to decode them. The destructive conflicts that rage in countries like Iraq and Syria, which entail brutal attacks on civilian populated areas and large-scale displacement, create severe disruptions in literacy attainment of tens of thousands of children. At critical moments of their development, many children are torn out of school and into protection and humanitarian crises and refuge. If their process to attain automatized reading is interrupted for years, these children may have forever lost their chance to become literate.

Literacy as Vital Life Skill

Not only is acquiring and enhancing literacy skills throughout life an intrinsic part of the right to education – it also has the “multiplier effect” of empowerment, fuller participation in society, promotion of human rights and dignity, poverty eradication, gender equality, and more inclusive and sustainable societies. The benefits of literacy for the whole society cannot be overstated. This is also the promise of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

| Literacy is vastly important for the realization of fundamental human rights. Illiterate women and men are more vulnerable to ill health, unemployment, exploitation and human rights abuse. Incapable of realizing their full potential, individuals and communities are trapped in a cycle of poverty and exclusion – which lay the foundation for violence and strife. In their despair, many children and youth are drawn into armed groups amidst promises of reward and honor. |

| It is a driver for sustainable development, as it facilitates participation in the labor market and provides life opportunities, improves child and family wellbeing, and reduces poverty. Reversely, youth and adults that lack basic literacy skills cannot grow to their full potential and are excluded from full participation, and are thus unable to contribute to sustainable development and empowerment of their communities and societies. |

| Acquiring literacy and pursuing education equips people with the essential skills needed to participate in political processes constructively and nonviolently. Education and literacy facilitates people’s understanding of and engagement with their political system and the underlying causes of social issues. Through participating in electoral processes or non-institutional activities such as demonstrations, the electorate and polity become more representative of society, governments are held to account, and constitutionally guaranteed rights are safeguarded. While restrictions on and censorship of information pose a challenge, literacy can enable people to access information through alternative channels. It is hence an indispensable tool to bring about social and political change. |

| While gender parity in literacy rates has steadily decreased, two thirds of the 758 million adults unable to read or write a simple sentence are women. Fostering literacy and equal learning opportunities also helps make strides towards the promotion of women’s rights and gender equality, including encouraging women in leadership positions. This in turn helps reduce gender gaps in education and literacy rates, particularly because women are presented with positive role models and increase their educational aspirations and achievements. |

| Literacy is also cornerstone in providing marginalized people with access to justice and legal protection. If people have a sense of exclusion from justice, including when they are unable to address their legal needs and to assert and protect their rights due to lacking literacy and education, they are prone to resorting to violent means, thereby undermining the prospects of peace. For lack of peaceful alternatives, marginalized groups may resort to violent methods to resolve their grievances. Literacy in the predominant administrative language of one’s country is often essential prerequisite to attaining the discussed rights. |

| In peacebuilding agendas, equal education plays a pivotal role for fostering social cohesion and for mitigating tensions. The perpetuation of inequality in education rooted in ethnic and religious differences heightens the risk of conflict. Institutional environments must not perpetuate segregation as legacy of conflict but instead reintegrating post-conflict communities and address differences between ethnic and religious groups. Integrated educational institutions have been found to counteract divisions, promote less sectarian perspectives and more tolerance, and positively impact minority group identity. |

Equipped with literary skills, people can speak out against injustice and state policies and practices. Digital technologies can provide a mouthpiece to voice concerns and can reach an international audience.

|

Literacy in a digital world As has been shown, literacy is a means of communication, understanding, identification, interpretation, expression, and creation. Its importance is expanding and diversifying in a growingly digital, information-rich, and text-mediated world. With the pervasiveness of digital technologies in every part of our lives, digital literacy is essential to reap associated benefits. Not only do people need access, they also require skills in interpreting, understanding, and communicating data. Marginalized groups need to acquire the literacies they deem relevant to use digital technologies to their benefit – as tools of empowerment, of expression, of making their voices heard. This becomes particularly relevant in contexts of conflict – in which parallel wars are often fought online. The otherwise voiceless must acquire digital literacy to tell their part of the story to ensure that justice will prevail. |

The Silent Victims of War: Literacy and Education

Armed conflict has an extremely detrimental effect on education systems and literacy rates. Almost 21.5 million children of primary school age and 15 million adolescents of secondary school age are out of school in conflict-affected areas. The proportion of out-of-school children in conflict-ridden countries had risen to 35 percent by 2015. In Northern Africa and Western Asia, the share amounts to a staggering 63 to 91 percent (UNESCO, 2016). More than 13 million children were prevented from going to school as a result of the protracting conflict and political upheaval across the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) in 2015 (UNICEF, 2015).

Educational institutions, students and teachers are being battered on the frontline of conflict. Deliberate and indiscriminate attacks on schools by state and non-state actors are vast, with relevant actors failing to distinguish between combatants and civilians. Government armed forces and other groups turn educational institutions into military posts and arms depots, risking students’ and teachers’ lives and safety. Schools are leveled to the ground and those teaching, learning, and playing in them are injured and killed. Access to and quality of education is heavily compromised and safe learning spaces are obliterated. During the conflict in Iraq in 2003-2004, 85 percent of schools were damaged or destroyed by fighting. In Syria, more than one quarter of schools were either destroyed, or forced to close, or used for fighting or shelter by 2016.

Forced recruitment of children into armed forces has mounted, abduction often preceding the forced and traumatizing incorporation of a child soldier into the armed group. Being denied formal education and sustaining severe bodily and mental harm, children see their rights to education and literacy disintegrate – often permanently.

The internally displaced, asylum seekers and refugees often have a long and protracted road ahead until finally being resettled. This compromises prospects of durable solutions, including sustained quality education. According to the UNHCR, 50 percent of primary school-age refugee children and 75 percent of adolescent refugees at secondary level are out of school. Refugees are five times more likely to be out of school than their non-refugee counterparts. Those that do receive schooling usually face shortages of qualified teachers, overcrowding, inadequate facilities, lacking material, and vulnerability to attacks. Official learning validation and certification essential for the future of refugee children are mostly neglected. Particularly women and girls, the poor, and minority groups are disproportionately affected by the devastating consequences of armed conflict for educational and literary attainment. This sheds a grim light on the prospects for SDG 4.5, which sets out to “eliminate gender disparities and ensure equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples and children in vulnerable situations”.

Armed conflict interrupts or even reverses progress in education. Especially in Iraq and Syria, former achievements in education and literacy rates have been starkly reversed.

Iraq

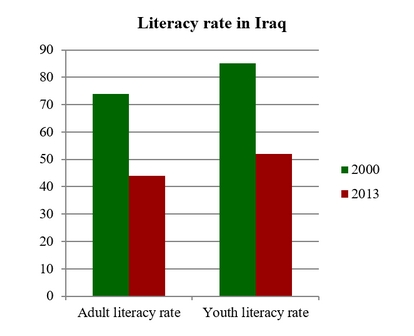

The sanctions, invasion, occupation, and ensuing armed conflict in Iraq have devastated historically high literacy rates and have ravaged the educational system. Prior to 1991, Iraq’s education system was one of the best in the region, with 100 percent gross enrolment rate for primary schooling and a high literacy rate for men and women. While the adult literacy rate still amounted to 74 percent and the youth literacy rate to 85 percent in 2000, they had drastically decreased to 44 percent and 52 percent by 2013, respectively. Currently, an estimated five million Iraqis are illiterate, including 14 percent of school age children who lack access to education. While 22 percent of adults have never attended school and only 9 percent have completed secondary education country-wide, a striking 47 percent of women are illiterate in some areas.

The escalation of conflict between armed groups and government forces, in which all parties commit flagrant violations of international human rights and humanitarian law, entails widespread attacks on civilian populated areas and vital public facilities such as schools and hospitals. Coupled with decades of under-investment and mismanagement on the part of the Iraqi government, the ravaging armed conflict deprives civilians of basic services.

|

An Iraqi boy in a music school that has not been restored since it was destroyed during the US-led war on Iraq. (Julie Adnan/Reuters) |

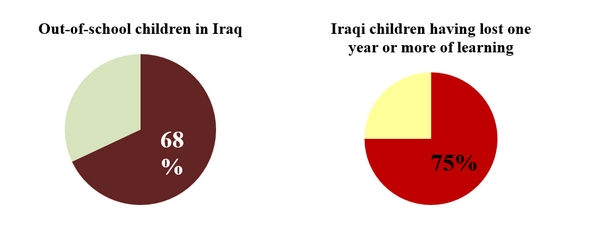

The immense violence and displacement has dismantled the education system in Iraq, with over 3.1 million children being affected by the crisis. 68 percent (over 550,000) of school-aged children are not in school. Over 75 percent of these children have been deprived of an entire year of learning.

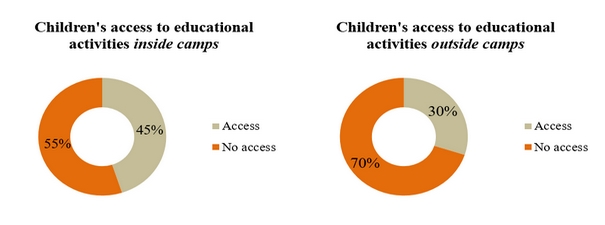

Hundreds of thousands of children aged 4 to 5 are internally displaced and are in urgent need of specialized early childhood care and support. Safe learning environments for children and adolescents are scarce – only 45 percent of the 78,000 school-aged children between 6 and 17 living in camps can access educational activities, while even less (around 30 percent) of the 730,000 children outside of camps have this opportunity. The grave security situation, inadequate educational facilities and resources, different curricula and language barriers are inhibitive factors to education – while the number of enrolled students varies across governorates.

With the vast influx of IDPs, the education infrastructure in host communities across Iraq is further debilitated. Over 1,500 school buildings are employed for housing the displaced and over a hundred schools are occupied by armed groups in areas where fighting continues. Especially displaced children require urgent psycho-social assistance. Children remaining in areas under ISIL control see greave oppression of educational freedoms, with sciences, art, music, history and literature having been eliminated from curricula. In “liberated” villages, schools and vital infrastructure lie in ruins – while little resources are invested in their restoration by the corrupt Iraqi government.

Syrian refugee children hosted in Iraq also have extremely limited access to education and can, if at all, only attain basic education, with few resources invested in secondary or higher education.

Syria

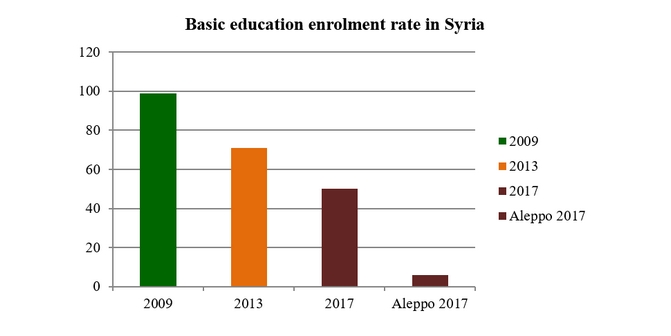

As a country having made great strides to promote the value of education and having reached a 95 percent-plus literacy rate before the war, Syria has now lost its people’s future to the war. Syria had achieved universal primary enrolment and relatively high secondary enrolment by 2001, according to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). Amounting to 98.9 percent in 2009, primary enrolment declined to under 71 percent in 2013 as the civil war was spreading.

As the war in Syria is in its seventh year, Syria is estimated to have one of the lowest enrolment rates in the world. Enrolment in conflict-ridden areas like Aleppo is as low as 6 percent, while half of refugee children are deprived of education. 534,000 Syrian refugee children in Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, Egypt, and Turkey and a total of 2.3 million Syrian children around the world are not enrolled in formal education. The education of Syria’s children has fallen victim to the bloodbath, to displacement and insecurity.

Inside Syria, about 1.75 million children and youth are out of school, with the majority lagging behind to up to six years in their reading and math skills2. Many more are at risk of dropping out. Out of Syria’s traditionally operating 22,000 schools, a third is damaged or unusable. At least 7,400 schools are closed and those that remain open show poor facilities and water, sanitation and hygiene conditions. The Syrian government has reportedly converted thousands of schools into detention and torture centers, while numerous other schools have been turned into military barracks. Others are deserted as parents keep their children at home for fear of attacks.

Quality of education has degenerated, roughly 150,000 teachers have left the education system, and dangers on the way to school and in school are substantial. Excessive violence, bomb threats, perilous access to schools, and disruption of the home environment and family structure have left severe marks on Syrian children’s physical safety, wellbeing, and ability to learn. Prolonged extreme levels of stress significantly impede children’s brain development. This is starkly reflected in research: According to a recent survey by the International Rescue Committee, 59 percent of 6th graders, 52 percent of 7th graders, and 35 percent of 8th graders could not read a simple 60-word story intended for second-graders. Almost half of the 3,000 13-year-old Syrians surveyed were unable to complete a math task designed for 7-year-olds.

Refugee children face immense obstacles to education. In Lebanon, the country hosting the largest number of Syrian refugees, 78 percent of Syrian children are out of school. The already limited capacity of public education systems in host countries is often overstretched, preventing many Syrians from attending school. Moreover, refugee families – many of which have lost everything – face acute financial difficulties and can seldom afford to send their children to school. Instead, many children are forced into child labor and early marriage, which renders any future return to education unlikely. Those who are fortunate enough to receive some access to education soon realize that it is inadequate – with unfamiliar curricula, language barriers, overcrowding and discrimination against Syrian children being predominant obstacles to learning.

Importance of Literacy in Iraq, Syria, and Beyond

The denial of the right to education and literacy is a silent yet pervasive assault on children. Young people who lack access to education and low literacy skills get trapped in a cycle of poverty, unemployment and low-paid jobs, which prevents them from growing to their full potential and contributing productively and positively to their society and communities. Instead, many are forced into child labor and early marriage or turn to negative coping behaviors. It can also render young people vulnerable to extremist ideologies and recruitment by armed groups offering a source of income and prestige. Returning to school also provides children with a sense of stability in their lives, enhancing their wellbeing and positive coping strategies. While education and the attainment of literacy is an individual human right, these are also vital for the future recovery, rebuilding and stability of war-ridden countries like Syria and Iraq. Access to quality education is key to ensuring attainment of livelihood for oneself and the family as well as socioeconomic development of the countries.

Furthermore, lacking literacy and education makes people vulnerable to political and social manipulation and prevents them from accessing and employing important channels of information. This is a particularly pertinent issue in our digital age. A parallel war is being waged online in conflict zones – a war of images, text, icons, pictures and symbols. The strongest weapon is state control over media and communication channels, which forbids dissident voices from speaking. While government entities may seek to forcefully repress the right to opinion and expression, digital pathways are sought and used by affected civilians to unveil what is being covered. Civilians being trapped in the fighting exchange information about new developments and share descriptions and images with the outside world – revealing the crimes committed by the parties to the conflict, as well as the abysses of the inflicted suffering. Armed only with their mobile phones and pens, they archive the falling of bombs from the sky, the mutilated bodies, and thousands of testimonies from affected people to collect evidence for future prosecution against all committed crimes.

Digital literacy is indispensable for the effective interaction with digital technologies and online platforms, through which those affected by armed conflict can share the developments on the ground, can direct attention to the human rights abuses being committed, and can help hold perpetrators accountable for their crimes.

Ordinary Iraqis and Syrians courageously engage in such activities. For instance, a shocking video published on the internet on 11 November 2016 shows a young Iraqi boy being crushed by a tank following the orders of a group of men wearing military uniform. The child, identified as Muhammad Ali Al-Hadidi, was dragged to the tank and shot seven times before being knocked down by the military vehicle. The online publication of this incident – which is far from being singular – provides crucial evidence for the human rights abuses committed by Iraqi security forces and government-backed militias under the pretext of “fighting terror”.

The appalling crimes of Iraqi government forces were once again revealed in a video published on 28 June 2017 by the Swedish newspaper EXPRESSEN, in which Iraqi police beat, torture, and arbitrarily kill alleged ISIS fighters in Mosul. Blindfolded men are shown with their hands tied behind their backs and beaten with whips and metallic cables, and suffocated by Iraqi soldiers. This illustrates the alarming pattern of indiscriminate and excessive use of force in the “war on terror”.

The video can be viewed here [Warning: Graphic images]

In the aftermath of the appalling chemical attack on April 4, 2017 in the rebel-held civilian neighborhoods in Southern Idlib and Northern Hama in Syria, photos and footage emerged showing the gravity of the situation on the ground: they showed children struggling to breathe and the half-naked bodies of the victims piled one over the other.

Some footage can be seen here [Warning: Graphic images]

The dangers of employing digital competencies in this manner can be drastic – with civilians being persecuted, arrested, tortured and killed for the publication of video and photo material or critical contributions on YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, or other platforms. Yet, in contexts of conflict, digital literacy of those whose voices are being silenced is a crucial weapon that is courageously used in the fight for justice – to provide evidence and ensure accountability for committed crimes when peace processes and political transition begins.

GICJ’s Position and Recommendations

GICJ would like to emphasize that people not only have the right to education in any context but that education can also protect them and give them a voice in times of conflict. Literacy is essential for the documentation of abuses and upholding of justice amidst armed conflict, without which the eventual attainment of stability and peace is impossible. In post-conflict situations, literacy and quality education are core drivers for post-conflict recovery and sustainable peace and development. Literary skills and education enable people to participate in political processes and the economic life of their country, and equip them with the necessary skills to become active parts in their communities.

Digital literacy can also be a fruitful force in the building of society after conflict, when it opens up channels for the expression and exchange of cultural identity, ideas, and strategies.

As children are remarkably resilient, the negative effects of armed conflict can be mitigated when children are provided with the needed support, notably safe and quality education. Such safe learning spaces must be provided even in the context of active conflict, through the provision of adequate facilities or, if needed, support for home-based learning activities. Yet, reading automaticity must be achieved in childhood, and by age 19 at the latest. To this effect, GICJ urges the international community, especially the United Nations bodies, to take all necessary measures to:

• Repair and rehabilitate educational institutions (including WASH facilities) in all areas of armed conflict;

• Provide temporary learning spaces, including facilities for early childhood care and education.

• Provide adequate and quality teaching and learning materials, with the fundamental objective of achieving a transition to reading automaticity at young age.

• In this regard, basic digital skills should be taught to ensure that the benefits are extended to all.

Importantly, psycho-social support (PSS) to children and teachers must be integrated in the education response. Therefore, GICJ calls upon relevant stakeholders to facilitate the training of education personnel in PSS as well as in inclusive education.

It is impossible to adequately address the denial of the rights to literacy and education in countries struck by conflict, notably in Iraq and Syria, without addressing blatant violations of international humanitarian and human rights law by all relevant parties to the conflicts, including the governments and state supported armed forces. If the international community fails to address the horrendous crimes committed by these actors, fundamental human rights – including the rights to education – will be further trampled and literacy rates will continue to drop. This will not only jeopardize the future of millions of young people but also derail any peace efforts and sustainable development.

It is therefore paramount for the international community to hold all perpetrators of crimes accountable and to scrupulously abide by their international obligations, including by ensuring the safe access to quality education in and outside of crisis affected areas. We would like to commend the resilient and courageous work by civil society actors and humanitarian personnel in an effort to provide children with direly needed care and educational support, and to render their lives a little happier.

1. This is because the ability of children to automatize a vast set of symbols, which requires the activity of certain neural circuits involved in perception, gradually slows down during adolescence.

|

Read online or download the full report. |

Day of Remembrance articles by GICJ: