14.06.2018

Report on the changes in legislation of south-eastern European countries for the incorporation of the EU Directives regarding the asylum procedures and the reception of asylum seekers (Directives 2013/32/EU and 2013/33/EU)

By: Konstantinos Kakavoulis

Contents:

The adoption of Directive 2013/32/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council on common procedures for granting and withdrawing international protection (recast) (hereinafter Directive 32) and Directive 2013/33/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down standards for the reception of applicants for international protection (recast) (hereinafter Directive 33) in June 2013, together with the recast Dublin Regulation and the recast EURODAC Regulation, constituted the final step in the second phase of harmonisation of asylum law in the EU Member States. The purpose of the Directives is to establish common procedures for the reception of applicants for international protection and for granting and withdrawing international protection.

The goal of Directive 32 was that individuals, regardless of the Member State in which they lodged their claim, “are offered an equivalent level of treatment as regards reception conditions, and the same level as regards procedural arrangements and status determination”. Directive 32 aimed at increasing the fairness and efficiency of asylum procedures in the EU, as well as the simplification of procedures and procedural concepts, including the reduction of exceptions to procedural guarantees, enhancing guarantees with respect to accessing the procedure, and introducing additional guarantees such as the right to legal assistance at the first instance and specific guarantees for vulnerable applicants.

Directive 33 aims at improving standards on reception conditions for applicants for international protection to ensure a dignified standard of living and comparable living conditions in all Member States. The harmonisation of reception conditions for applicants for international protection may contribute to more adequate protection of asylum seekers’ fundamental rights in the application of the Dublin III Regulation, as domestic and European courts consider that effective access to adequate reception conditions is a key consideration in the lawfulness of transfers between Member States under the responsibility-allocation system.

The Directives introduce a number of positive changes, which if correctly transposed and implemented in practice, would lead to improved and equal reception standards and treatment for many asylum seekers throughout the EU.

|

Asylum seekers arriving in EU territory by sea. |

Member States are under an obligation to transpose and implement these Directives in a manner which is consistent not only with the 1951 Convention on the Status of Refugees, but also with other relevant instruments such as the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), the Convention against Torture (CAT), the International Convention on the Rights of the Child (CAT), International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women and the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. In fact, obligations deriving from international human rights law, the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights as well as general principles of EU law, may require Member States to go beyond the level of procedural guarantees laid out in the Directive with regard to certain provisions as allowed by Article 5 of the Directive.

Despite the aforementioned obligations, the Directives left considerable room for manoeuvre to Member States regarding the way the imposed standards may be transposed and implemented into national legislation. Interestingly, the Directives no longer foresee only “minimum standards”, but encourage Member States to interpret the provisions in the Directives in a positive and generous spirit. The four south-eastern EU countries (namely Greece, Malta, Cyprus and Italy) have all taken legislative action in order to incorporate the Directives into their national legislation. The present report aims at examining and evaluating the level of actual incorporation of the Directives in these legal orders. While the stream of persons seeking international protection in Europe seems to be constantly high, if not increasing, it is of the utmost importance that all Member States enforce a commonly agreed legislative and policy plan. We are probably witnessing the biggest displacement of populations of all times. This situation may be confronted only through co-operation and compliance with European and international law. The key geographical position of the south-eastern EU countries and their role as the first points of entry into the EU, makes their compliance with the Directive, as well as EU asylum law, imperative. The present report does not introduce the whole legal framework of the four south-eastern EU countries regarding asylum. It is confined to addressing the most important issues in their legislation regarding the incorporation of the Directives.

1. Greece

a) Directive 32

Greece fully transposed Directive 32 primarily through Law No. 4375, published on 3-4-2016 in the State Gazette. On the 16th of June 2016, the Greek Parliament approved an amendment (L 4399/2016 , Article 86) to its asylum law (L 4375/2016). Both laws refer to “The organization and operation of the Asylum Service, the Appeals Authority, the Reception and Identification Service, the establishment of the General Secretariat for Reception, the transposition into Greek legislation of the provisions of Directive 2013/32/EC on common procedures for granting and withdrawing the status of international protection (recast) (L 180/29.6.2013), provisions on the employment of beneficiaries of international protection and other provisions”. These are the two State laws under which Greece has incorporated Directive 32 into its national legal order and which will be examined under the present report. The two 2016 Laws overhauled the procedure before the Greek Asylum Service.

Law 4375/2016 consists of 83 Articles. Articles 1-32 refer to the establishment of the Services and Authorities mentioned in the title of the law. Articles 32-66 incorporate Directive 32 into the Greek legal order, while Articles 67-83 provide for procedural guidelines for the entry into force of the Law. The whole substance of the Directive is transposed throughout the pertinent provisions of L 4375/2016, adapted to the necessities in the receiving State and the existing mechanisms and structures.

One of the most important modifications created by L 4375/2016 is the fast-track border procedure under Article 60, which transposes Article 43 of Directive 32. The procedure is mostly used as an admissibility procedure to examine whether applications may be dismissed on the ground that Turkey is a “safe third country” or a “first country of asylum”. Although these concepts already existed in Greek law, they have only been applied in the wake of the EU-Turkey statement of 18 March 2016. It must be underlined that this fast-track border procedure does not apply to family cases processed under the Dublin Regulation and vulnerable cases. A Joint Action Plan of the EU Coordinator on the implementation of certain provisions of the EU-Turkey statement recommends that Dublin family reunification cases be included in the fast-track border procedure and vulnerable cases be examined under an admissibility procedure. On the other hand, it is worth noting that “the fast-track procedure under derogation provisions in Law 4375/2016 does not provide adequate safeguards” for the rights of migrants. According to the UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants, the procedure should be based on the personal condition of the asylum seekers and their level of vulnerability rather than their nationality. It is also important to note that Article 22 of L 4375/2016 explicitly stipulates that asylum seekers who have lodged their asylum applications up to five years before its entry into force (3 April 2016), and their examination is pending, shall be granted a two-year residence status on humanitarian grounds, which can be renewed. This provision makes feasible the smooth transition between the old and new legislation on international protection.

Part II (Articles 36-50) of L 4375/2016 transposes Articles 6-13 and 19-30 of the Directive regarding the rules for the registration of asylum seekers and the lodging of applications. It is evident that these provisions were drafted taking into account the vast number of asylum seekers and appellants in the Eastern Greek islands, as well as the difficulties that this intense workload might create for the Greek authorities. Therefore, while the Asylum Service shall as soon as possible proceed to the “full registration” of the asylum application, following which an application is considered to be lodged , if “for whatever reason” full registration is not possible, the Asylum Service may conduct a “basic registration” of the asylum seeker’s necessary details within three working days, and then proceed to the full registration as soon as possible and by way of priority. Additionally, the time limits of three or six working days respectively for the basic registration of the application may be extended to ten working days in cases where a large number of applications are submitted simultaneously and render registration particularly difficult. It is also worth noting that no time limit is set by law for lodging an asylum application. The application should be examined as soon as possible, and in any case within 6 months. This period may be extended for up to 12 more months, in exceptional circumstances.

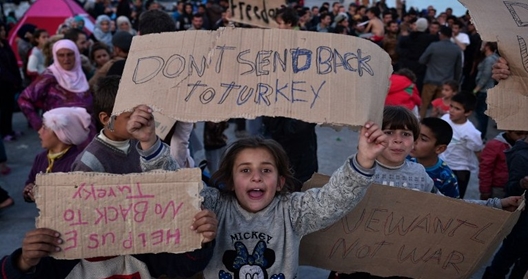

An evident drawback of L 4375/2016 is the “first country of asylum” concept. While Article 55 does no more than transpose Article 35 of Directive 32, it must be noted that this provision lowers the guarantees applicable to the “first country of asylum” notion compared to the previous legal framework. Although the previous legal framework required the Asylum Service to take into account the safety criteria of the “safe third country” notion when examining whether a country qualifies as a “first country of asylum”, there is no such prerequisite under L 4375/2016. A possible repercussion is that an application may be considered inadmissible on the ground of the first country of asylum even if said country, in the current context Turkey, does not satisfy the criteria of a “safe third country”.

|

Young asylum seekers demand not to be sent back to Turkey. |

On the 16th of June, the Greek Parliament approved an amendment (L 4399/2016) to L 4375/2016, in response to reported EU pressure on Greece to respond to an overwhelming majority of decisions rebutting the presumption that Turkey is a “safe third country” or “first country of asylum” for asylum seekers. L 4399/2016 modified the composition of Appeals Committees and the right of asylum seekers to be heard in appeals against negative decisions. Under L 4399/2016, the Appeals Committees consist of two judges from the Administrative Courts, appointed by the General Commissioner of the Administrative Courts, and one UNHCR representative. A representative from a list compiled by the National Commission of Human Rights may take part in the Appeals Committees if UNHCR is unable to appoint a member. In addition, the amendment removed Article 62(1) of L 4375/2016, which allowed the appellant to request a personal hearing before the Appeals Committees at least two days before the appeal. According to the country report by Asylum Information Database, the reforms have not yet changed the situation in practice, since the Appeals Committees tend to reaffirm the first instance decision in more than 99% of the cases.

It can be concluded that Greece has adequately transposed Directive 32 into its national legal order. This fact has to be hailed, taking into account the key geographical position of the country and the amount of asylum seekers it receives on a constant basis. Undoubtedly, certain aspects of Greek legislation have to be reviewed, such as the notions of “first country of asylum” and “safe third country”. While there is always room for improvement, it can be claimed that Greek legislation is moving in the right direction regarding the incorporation of Directive 32 and the grant of international protection.

b) Directive 33

Greece partially transposed Directive 33 through Law 4375/2016, Article 46. Hitherto, only Articles 8-11 of Directive 33 have been incorporated in the Greek legal order, although the deadline for the transposition expired in July 2015. A draft law on the transposition of Directive 33 was submitted for public consultation. This procedure was carried out with the participation of NGOs and came to an end on 31 October 2016. By April 2018 the bill had yet to be introduced to the Parliament. Therefore, Presidential Decree 220/2007 transposing Directive 2003/9/EC, laying down minimum standards for the reception of asylum seekers, is still applicable.

|

Refugee children queuing in Greece waiting to receive material reception conditions. |

The provisions, which have already been transposed, relate to the detention of asylum seekers. Article 46 of Law 4375/2016 is comprised of 11 paragraphs. The first two paragraphs do no more than incorporate Article 8 of Directive 33 without any amendments. Paragraph 2 specifically determines the grounds for detention, as required in Directive 33 Article 8(3). The list of grounds for detention is exhaustive. Nonetheless, the grounds stipulated leave room for a wide margin of discretion when it comes to their interpretation. For instance, paragraphs 2(b) and (e) prescribe the “risk of absconding” as a reason for detention. Although certain criteria to determine the aforementioned risk exist in the Greek legal order, these criteria are not exhaustive and the “risk of absconding” may be interpreted in a wide sense. Following the EU-Turkey statement, it has been observed that upon arrival all migrants in the Greek islands are detained on presumed risk of absconding. This risk constitutes an “automatic assumption and is not supported by any specific documents.” Such automatic assumptions should be avoided and an individual case assessment should be carried out, as required by the EU Return Handbook. The EU-Turkey statement was meant to be “a temporary and extraordinary measure... necessary to end the human suffering and restore public order”. Nevertheless, two years after its release, it has become a steadfast phenomenon, which, among others, reinforces the containment policy in the Greek islands, while the human suffering it was meant to address is still present.

Another point on which the law leaves a wide margin for interpretation is Law 4375/2016, Article 46(2)(d). According to this provision, a person posing a threat to public order may be detained. This provision can be, and has been, misinterpreted. As reported, “public order” grounds have been extensively used to justify detention. Notably, such detention orders are scarcely properly justified. A police circular released on 18 June 2016, with the intention to specify the public order grounds, provided that third country nationals with “law-breaking conduct’ will be transferred from the islands and detained in pre-removal centres on the mainland. As a result of this circular, more than 1,600 people had been transferred and detained on the mainland, as of March 2017. Although up to date data are not available, it cannot be expected that such massive detention orders are properly justified. This is further proven by Administrative Court orders on objections against detention on public order, which in many cases have decided that “from the nature of the offense it cannot be inferred that he presents a threat to national security or public order” or that “the gravity of the offense charged against him is not of such gravity as to attribute a danger to public order” or that “the details of the case do not justify detention on public order grounds”. Another point of concern stems from paragraph 2(c), which provides that detention may be ordered when “the applicant is making the application for international protection merely in order to delay or frustrate the enforcement of a return decision”. This constitutes a very vague provision, which gives the authorities a wide margin of discretion in deciding positively on detention orders.

The legal incorporation of the prerequisites set by Directive 33 regarding the grounds for detention does not seem to be problematic, apart from the automatic assumption of a risk of absconding and the consequent detention of newly arrived asylum seekers. Nevertheless, the large margin of discretion left to the authorities when interpreting the pertinent provisions, should be carefully monitored. The only feasible way for this is the provision of complete and detailed reasoning when a detention order is taken. According to official statistics, 14,864 non-citizens were detained in pre-removal detention centres in 2016, of whom 4,072 were asylum seekers. The number of asylum applications submitted from detention was 2,829 in 2016 and 2,543 in 2015. While no data are yet available for 2017, it is highly unlikely that all these detention orders are promptly and comprehensively justified, as required by Law 4375/2016 Article 46(3), transposing Directive 33 Article 9(2) and (3).

In regards to Directive 33 Article 8(4), which stipulates that alternatives to detention should be prescribed under national law, it has successfully been transposed by Greece, but not successfully implemented. Law 4375/2016 Article 46(2) provides that detention shall be ordered only when no alternative measures can be applied. The aforementioned provision cites Law 3907/2011 Article 22(3). The latter furnishes a non-exhaustive list of alternatives to detention. Unfortunately, such alternatives are often not considered by the authorities and no individual assessment of the cases is made.

Moreover, Greece has legislated regarding the detention of vulnerable persons, thus incorporating Directive 33 Article 11. In particular, it is stipulated that women are detained in a separate area from men, while they should not be detained during pregnancy and for three months after labour. Additionally, the privacy of families in detention should be respected. Special provision is also made for minors, who should be detained only as a “last resort solution”, for the sole purpose of ensuring that they are safely referred to appropriate accommodation facilities. Despite the prompt legislative measures taken, the number of unaccompanied minors held in unsuitable conditions has increased alarmingly. As of 19 July 2017, an estimated 117 children were in police custody awaiting transfer to a shelter. These children are detained in conditions which have been reported to be “deplorable, leaving children at heightened risk of abuse, neglect, violence and exploitation.” What is more, it has been reported that the fear of detention impels children to be registered falsely as adults. This leads them to losing the advantages offered to unaccompanied minors under Greek and international law. Notably, there are two cases pending before the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), which inter alia concern the cases of unaccompanied migrant minors, held in police custody. The applicants complain that their detention conditions were in violation of Article 3 of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR), while they challenge the legality of their detention as contrary to Article 5. Whilst Greece has been condemned by the ECtHR time and again for violations of the same articles in cases of detained minors, it seems that it is a continuous problem and the authorities need to address it.

According to Greek law, the duration of detention varies according to the grounds on which the detention was ordered, but in any case cannot exceed 3 months. This provision transposes the requisite set by Directive 33 Article 9(1), namely that detention of applicants shall be as short as possible. It should be underlined that Law 4375/2016 considerably reduces the maximum length of detention, which was up to 18 months, according to the previous legislation. This progression must be welcomed. However, these time limits start running from the moment that the migrant is considered as an applicant for asylum, thus from the moment his asylum application is properly registered with the Greek Asylum Services. While delays in the registration of applications are not an unusual phenomenon, asylum seekers are often detained in practice for a longer period than the one prescribed by the law. Special reference should be made to the length of detention of unaccompanied minors. According to Directive 33 Article 11(2)(a), if minors are detained as a last resort solution, their detention shall not exceed the time period strictly necessary. This provision is reflected in Law 4375/2016 Article 46(10)(b), which prescribes that minors can be detained for a maximum period of 25 days. In exceptional circumstances, detention may be prolonged for another 20 days. Nevertheless, the Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants noted that asylum-seeking children are frequently detained for longer than 45 days.

|

Minor asylum seekers at a detention centre in the village of Filakio near the Greek-Turkish borders. |

In regards to detention conditions, Greek legislation stipulates that the applicants must receive appropriate medical care and be entitled to actual legal representation. While Greek law states that “shortages in adequate premises and the difficulties in ensuring decent living conditions for detainees” must be taken into account when detention orders or orders prolonging detention are made, there is no guarantee that detainees have access to open-air spaces, as required by Directive 33 Article 10(2).

Greek legislation provides for an automatic judicial review of detention orders, as required under Directive 33 Article 9(3) and (5). Apart from this ex officio judicial review, Law 4375/2016 gives detained applicants the right to challenge the detention themselves. The latter provision is quite problematic, since the procedure that must be followed by the applicants is the one under a 2005 law. The ECtHR has found this procedure to be an ineffective remedy, contrary to ECHR Article 5(4) on several occasions. Last but not least, although Directive 33 Article 9(6) prescribes that Member States shall “ensure that applicants have access to free legal assistance and representation” in case of a judicial review of the detention order, and Greece has transposed the pertinent provision in its national legal order, it has fallen short in practice. Although Greek law states that “detainees who are applicants for international protection shall be entitled to free legal assistance and representation to challenge the detention order...”, no free legal assistance system has been set up yet. Free legal assistance is provided only by NGOs. This clearly does not exempt Greek authorities from their obligation under Directive 33 Article 9(6).

In sum, Greece must urgently take legislative action in order to incorporate Directive 33 into its national legislation. The deadline for such a transposition has long expired and Greece has selectively transposed only four Articles of Directive 33. Much more legislative action regarding the reception of applicants is expected from the EU Member State, which ranks first in the reception of asylum seekers. It is also imperative that Greece reviews its current legislation regarding the detention of applicants seeking international protection. Although Law 4375/2016 transposes the pertinent Articles of Directive 33 in an acceptable fashion, it appears that either it cannot be effectively put into practice or its implementation should be more carefully monitored by the Greek authorities.

2. Malta

a) Directive 32

Malta has transposed Directive 32 through Legal Notice 416 of 2015 (Full title: Procedural Standards for Granting and Withdrawing International Protection Regulations, Legal Notice 416 of 2015, hereinafter referred to as “Legal Notice 416”). In general, Legal Notice 416 does not diverge much from Directive 32. It constitutes an incorporation of the Directive in the national legal order with minimal amendments.

One of the most important provisions of Legal Notice 416 is that although an asylum seeker is allowed to receive legal assistance for the preparation of his application on international protection at his own expense, in the event that he wishes to file an appeal against the decision, he is granted free legal assistance under the same conditions applicable to Maltese nationals. This provision constitutes a slight deviation from the Directive, which requires free legal assistance to be provided to asylum seekers at all stages of the procedure. However, Malta uses the margin of discretion provided by Article 22 of Directive 32 in deciding the terms and conditions under which an applicant is granted free legal assistance.

|

African migrants trying to reach Malta on a boat. |

It is also worth noting that a similar provision to the one under Greek Law 4375/2016 Article 36 is included in Legal Notice 416, setting exactly the same time frame regarding the registration of the asylum application. Moreover, the Legal Notice does not set a time limit for lodging an asylum application. The Refugee Commissioner shall ensure that the examination procedure is concluded within six months from the lodging of the application. The Commissioner may extend this time limit for a period not exceeding nine months for limited reasons, i.e. when complex issues are involved, when a large number of third-country nationals simultaneously apply for international protection or when the delay can clearly be attributed to the failure of the applicant to comply with his obligations. The examination procedure shall not exceed the maximum time limit of twenty-one months from the lodging of the application.

Legal Notice 416 provides for a systematic personal interview of all applicants for international protection but foresees a few restrictive exceptions. The grounds for omitting a personal interview are the same as those contained in Directive 32. Nonetheless, in practice the Refugee Commissioner never makes use of this provision and proceeds with interviewing all asylum seekers. It is notable that Malta makes use of the discretion provided under Directive 32 Article 17 (2) and Legal Notice 416 Article 11(2) which stipulate that the personal interview may be recorded in audio or audio-visual, provided that the ‘recording or a transcript thereof is available in connection with the applicant’s file’.

Regarding special guarantees for vulnerable persons, Legal Notice 416 does no more than transpose the framework provided by Directive 32. Regarding special guarantees for unaccompanied children, it foresees that they are assigned a representative no later than 30 days from the issue of the care, thus specifying the ‘as soon as possible’ prerequisite set by Directive 32. Regarding the provision of information to asylum seekers of the procedure, Legal Notice 416 states that asylum seekers have to be informed in a language that they understand or they may reasonably be supposed to understand, of, among other things, the procedure to be followed and their rights and obligations during the procedure. It also states that asylum seekers have to be informed of the result of the decision in a language that they may reasonably be supposed to understand, when they are not assisted or represented by a legal adviser and when free legal assistance is not available. It also covers the information about the consequences of an explicit or implicit withdrawal of the application, and information on how to challenge a negative decision. This provision does not, however, state in which form such information has to be provided except for the decision that, by virtue of Article 14 of Legal Notice 416, has to be provided in a written format. Therefore, the provision regarding the delivery of information to asylum seekers does not guarantee that the people it concerns fully understand it, since they are provided with the information orally and frequently under harsh circumstances.

The incorporation of Directive 32 by Malta does not diverge much from the text voted by the EU Parliament and the Council of Europe. It can be claimed that Malta has done the minimum in order to transpose Directive 32. This is not necessarily negative. It appears that the amendments made, reinforced by the national legislation, is now able to meet the existing needs regarding asylum seekers in the country. Although there are still a few issues which require further attention by the national authorities, it can be concluded that the transposition of Directive 32 has been a success in Malta.

b) Directive 33

Malta has incorporated Directive 33 throughout Reception of Asylum Seekers Regulations, Legal Notice 417 of 2015 (hereinafter referred to as Legal Notice 417).

Notably, Maltese legislation does not distinguish between the various procedures in order to determine entitlement of reception conditions. Legal Notice 417 is confined to stipulating that an “applicant means a person who has made an application for a declaration under article 8 of the Act”, which therefore is a person who has lodged an application for international protection. Since no specific determination is made, all applicants are entitled to reception conditions. It must also be stressed that there a determination for the duration of entitlement to reception conditions is not made either. The asylum seeker is entitled to reception conditions from the moment he lodges an application, and should receive all the pertinent information in writing from the Principal Immigration Officer within 15 days.

One aspect of Legal Notice 417 which should be highlighted is the definition of family members under Article 2. Despite the fact that this definition is broadly in line with the definition in Article 2 of Directive 33, it fails to recognize family bonds which may have been created subsequently to departure from the country of origin, for instance during or after flight, or in refugee camps. The latter results in excluding children born from those relationships from the guarantees laid out in the Directive, for example with regard to the maintenance of family unity. Maltese legislation should be amended in order to also include these family ties, which require the same level of protection as the ones formed in the country of origin.

Legal Notice 417 dictates that reception conditions are provided to “applicants [who] do not have sufficient means to have a standard of living adequate for their health and to enable their subsistence”. In case they have sufficient resources or have been working for a reasonable period of time, they might be required to cover or contribute to the cost of the material reception conditions and of the health care provided for in these regulations. However, the notions of “sufficient resources” and “reasonable period of time” are very vague and require further elaboration by the Maltese legal order. For this determination it is crucial that Maltese legislation provides for an assessment of the risk of destitution, made prior to the decision-making.

The same applies to access to health care; while Legal Notice 417 stipulates that the material reception conditions should ensure the health of all asylum seekers, there is no minimum threshold regarding the level of health care that should be ensured.

|

Asylum seekers receive medical treatment immediately after being rescued by the Maltese authorities in the Mediterranean. |

It is important that applicants who have been affected by a decision relating to reception conditions have the right to appeal before the Immigration Appeals Board. Nonetheless, not all applicants equally enjoy such a right. More specifically, applicants who are in detention face more problems, since they do not have access to information on how to access the Appeals Board and the pertinent procedures. The latter is also highlighted by the ECtHR in its Article 5 ECHR cases against Malta.

One lacunae in the Maltese law is that although it dictates that the level of material reception conditions should ensure a standard of living adequate for the health of asylum seekers, it does not determine this level adequately, nor does it define the meaning of “a standard of living adequate for the health of asylum seekers”. Therefore, there must be further legislative action towards the elucidation of the required level of material reception conditions; at the very least, a minimum threshold should be adopted.

Regarding the reduction or withdrawal of reception conditions, Legal Notice 417 provides for circumstances in which the asylum seeker abandons the established place of residence without providing information or consent, does not comply with reporting duties or with requests to provide information or appears for personal interviews concerning the asylum procedure.

It must be underlined that such decisions shall be taken “individually, objectively and impartially and reasons shall be given” with due consideration to the principle of proportionality. However, there is no legal definition of when a place of residence is considered abandoned.

Interestingly, Maltese legislation regulates access to the labour market in a fashion that has to be welcomed. It does not impose any limitations on the nature of employment asylum seekers may pursue and grants them access to the labour market after the lapse of 9 months from the date when the application was lodged. It also foresees that even in the event when an appeal is lodged against a negative decision regarding the granting of asylum, the applicant will enjoy access to the labour market even during the appeals stage. However, Legal Notice 417 is to be criticized as international protection may be offered prior to the lapse of the 9-month period. In reality, according to Directive 32 an application for international protection must be decided within 6 months from the date it has been lodged – except for special cases/circumstances. Therefore, it is perplexing why the time frame for access to the labour market is regulated at 9 months. Another problematic aspect is that in order for an applicant to be employed, he/she must possess an ‘employment license’ issued by the State. Such a license lasts from 3 to 12 months, but in most cases is limited to up to 6 months. This a defect in the Maltese legal order, which discourages employers from actually hiring asylum seekers.

Regarding access to education, Legal Notice 417 provides that asylum-seeking children are entitled to access the education system in the same manner as Maltese nationals. This may not be postponed for a period longer than 3 months from the date of submission of the asylum application. Only in exceptional circumstances, where “specific education is provided in order to facilitate access to the education system”, this period may be prolonged to1 year. Nevertheless, it must be underlined that there is no provision for a formal assessment process to determine the most appropriate entry level for children.

Regarding the definition of applicants with special needs, Legal Notice 417 transposes Directive 33 and provides that “an evaluation by the entity responsible for the welfare of asylum seekers, carried out in conjunction with other authorities as necessary shall be conducted as soon as practicably possible”. It also complies with the Directive 33 prerequisites for the special needs of vulnerable persons, providing for an age assessment or a vulnerability assessment, maintenance of family unity where possible and particular attention to ensure that material reception conditions are appropriate to guarantee an adequate standard of living.

Maltese legislation also adequately transposes Directive 33 in terms of detention. More specifically, the grounds for detention, as well as alternatives to detention, do not deviate from the provisions of Directive 33. Notably, Legal Notice 417 absolutely prohibits any form of detention of vulnerable persons. Furthermore, the maximum duration of detention is limited to 9 months. Moreover, the UNHCR, international organizations, health officials, legal counsels and accredited NGOs all enjoy access to applicants in detention. Judicial review of the detention order is also provided for in Maltese law and free legal assistance is awarded for such review. Other remedies are also available to detainees to challenge their detention, such as human rights action before the national courts, the application under Article 409A of the Criminal Code and the application under Article 25A of the Immigration Act. However, these remedies have been criticized for not being “speedy, judicial measures” by the ECtHR.

It can be concluded that Malta has transposed Directive 33 at a decent level. Maltese law provides adequate safeguards to applicants regarding their reception and detention conditions. This effort by Malta should be welcomed and more States should follow its paradigm. Obviously, there are vacuums in the Maltese legislation, which should be filled and there are certain provisions which require further elaboration. However, in total, the incorporation of Directive 33, as well as Directive 32, have been a success in Malta and this fact must be applauded.

3. Cyprus

a) Directive 32

Cyprus transposed Directive 32 through two laws adopted on 14 October 2016, namely The Refugees (Amendment) Law of 2016 N. 105(I)/2016 and The Refugees (Amendment) (No 2) Law of 2016 N. 106(I)/2016 (hereinafter referred to as Law 105(I)/2016 and Law 106(I)/2016 respectively). Article 31(3)-(5) of Directive 32 have not yet been incorporated in the national legal order. They are to be transposed by 20 July 2018.

One of the most remarkable modifications of the Cypriot legal order to comply with the prerequisites of Directive 32 is the establishment of the Administrative Court. The latter has taken over from the Supreme Court as the first instance judicial review authority for asylum decisions as of January 2016. In order to ensure that asylum seekers in Cyprus have a right to an effective remedy against a negative decision before a judicial body on both facts and law in accordance with Article 46 of Directive 32, the relevant authorities have taken steps to modify the procedure as follows: abolish the Refugee Reviewing Authority, which is a second level first-instance decision-making authority that examines appeals on both facts and law, but is not a judicial body, and instead provide a judicial review on both facts and law before the Administrative Court. Nonetheless, the Administrative Court examines applications made only after 20 July 2015 on both facts and law, the date upon which the transposition of Directive 32 was due. For applications made prior to the given date, the Administrative Court only examines on points of law. As a result, applicants who applied prior to 20 July 2015 will never have access to an effective remedy before a court or tribunal, as required by Directive 32.

One further deficiency of the 2016 laws is that they do not contain any provision regarding the state of a person who appears before the pertinent authority in order to submit an application for international protection, but does not manage to do so on that date and is given an appointment to return on another day (approximately three days to one week) to apply for asylum. According to Cypriot law, a person is considered an asylum seeker –and is entitled to the pertinent guarantees- from the day the asylum application is made up to the issuance of the final decision. Nonetheless, there are no guarantees for persons who attempted to file an application, but were not able to do so. Although in practice these persons are rarely arrested, this gap in Cypriot law is profound and must be revised. Another problematic aspect of the provisions in question is that they are not retrospective. Therefore, persons who sought asylum prior to 20 July 2015 are considered asylum seekers until “the date of notifying the decision of the Reviewing Authority”. As a result, asylum seekers from that point on are considered “prohibited immigrants” and deportation / detention orders can be issued against them; even prior to receiving notice of the negative asylum decision, and without being provided with a legal or an ex officio remedy or protective measures to determine their right to remain during the judicial review process. This is also an evident deficiency in the 2016 laws, which require further review.

According to Law 106(I)/2016, an asylum application is addressed to the Asylum Service, a department of the Ministry of Interior, and made at the competent Aliens and Immigration Unit, which, no later than three working days after the application is made, has to register it and refer it immediately to the Asylum Service for examination. In cases where the applicant is in prison or detention, the application is made at the place of imprisonment or detention. If the application is made to authorities who may receive such applications but are not competent to register such applications, then that authority shall ensure that the application is registered no later than six working days after the application is made. Furthermore, if a large number of simultaneous requests from third country nationals or stateless persons make it very difficult in practice to meet the deadline for the registration of the application as mentioned above, then these requests are to be registered no later than ten working days after their submission. The law does not specify the time limits within which asylum seekers should make their application for asylum; it only specifies a six day time limit between making and lodging an application. If an asylum seeker did not make an application for international protection as soon as possible, and without having a good reason for the delay, the accelerated procedure can be applied. It must also be noted that the ratione for the differentiation between the notions of ‘making’ and ‘lodging’ an application cannot easily be understood and creates several practical problems, such as the aforementioned non-provision of guarantees to persons who have made, but not lodged, an asylum application.

|

Syrian asylum seekers subsequent to their arrival in Cyprus. |

The Asylum Service shall ensure that the examination procedure is concluded within a period of six months of the lodging of the application, which can be extended for maximum of 12 months. Regarding personal interviews, the Cypriot laws abide by the framework provided by Directive 32 and -like the Maltese legislation- provide for an audio/audio-visual recording of the interview. It is worth noting that the 2016 laws allow access, for the first time before a decision is issued on the asylum application, to the interview transcript, assessment / recommendation, supporting documents, medical reports and country of origin information that have been used in support of the decision.

Another problem is the access to free legal assistance. On the first instance the examination of Law 106(I)/2016 introduces the obligation on the State to ensure, upon request, and in any form the State so decides, that applicants are provided with legal and procedural information free of charge, including at least information on the procedure in light of the applicant’s particular circumstances, and in case of a rejection of the asylum application, information that explains the reasons for the decision and the possible remedies and deadlines. Furthermore, the Head of the Asylum Service has the right to reject a request for free legal and procedural information provided that it is demonstrated the applicant has sufficient resources. The Head may require that any costs granted are to be reimbursed wholly or partially if and when the applicant’s financial situation has improved considerably or if the decision to grant such costs was taken on the basis of false information supplied by the applicant. All these provisions create a remarkably low threshold for the State to satisfy when examining requests for free legal assistance. Taking into account that the procedure before the Administrative Court is judicial and a legal representative is needed, it is easily concluded that this is not a procedure that is accessible to all asylum seekers, if the latter are not able to afford the expenses. This does not satisfy the prerequisite of Article 46 of Directive 32, namely access to effective remedy in the event of a negative decision. It is important to underline that this subject has concerned the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review of Cyprus among others. In its last report the Working Group included a recommendation to ensure that asylum seekers have free legal aid throughout the asylum procedure.

Law 105(I)/2016 introduces an identification mechanism, specifically it provides that an individual assessment shall be carried out to determine whether a specific person requires special procedural guarantees and the nature of those needs. Although a basic framework for the identification of vulnerable persons is introduced, the assessment tools and approaches to be used are neither defined nor standardised. Although the law stipulates that persons identified as vulnerable, should receive appropriate support within a reasonable time frame, the exact level, type or kind of support is not specified. Regarding the identification of minors, Law 105(I)/2016 is confined to transposing the framework described in Directive 32. Nonetheless, an amendment under the 2016 laws, which should be highlighted, concerns the representation of unaccompanied children. The laws stipulate that the Director of Social Welfare Services acts as a representative of unaccompanied children in the asylum procedures, but for judicial proceedings the Commissioner for Children's Rights is responsible for ensuring representation.

In general, apart from the cases described above, the 2016 laws mirror the provisions of Directive 32. For instance, as far as the notions “safe third country”, “safe country of origin”, “first country of asylum” are concerned, the 2016 laws do no more than echo the definitions of the Directive. It seems that there is considerable space for improvement in the Cypriot legal order in terms of the incorporation of Directive 32. In addition to the delay in the transposition of the Directive, the Cypriot legislation does not adequately respond to the actual and ongoing problems of persons in need of international protection. Taking into account that Cyprus is one of the first EU receiving countries regarding asylum seekers, there is an urgent need to review its legislation. The 2016 laws are definitely pointed in the right direction and should be used as a bedrock for further amendments to the Refugee Law.

b) Directive 33

Cyprus has transposed the Directive through Law 105(I)/2016. The Cypriot law stipulates that asylum seekers shall have access to material reception conditions during the administrative and judicial aspects of the procedure. There is only one prerequisite for the provision of material reception conditions: that the persons concerned are considered to be “asylum seekers”. Therefore, in cases when a person loses the “asylum seeker” label, such as after the return of the applicant to Cyprus under the Dublin Regulation with an already determined case or in the event that the person files a subsequent application following his rejection decision or additional elements to his/her initial claim, after the latter has been rejected, the person is not entitled to material reception conditions. Although the rationale behind this provision can be understood, it is seriously concerning that persons who are still vulnerable and in need of basic material reception conditions are left without aid.

In order for material reception conditions to be provided, the asylum seeker has to submit an application to the Social Welfare Office, by presenting a confirmation that the application has been made. Here lies the first grave vacuum in the Cypriot legislation. According to another provision of the law, the confirmation that the application has been made is provided 3 days after the application has been actually lodged. Additionally, the law allows 6 days to lapse between making and lodging an application. Therefore, the Cypriot legislation is problematic in terms of provision of material reception conditions to persons of concern during the first crucial days subsequently to their arrival in EU territory. It is during these first days when material reception conditions are needed the most, but this fact has still not been taken into account by the Cypriot legal order.

Law 105(I)/2016 provides that material reception conditions are provided to applicants to ensure an adequate standard of living capable of ensuring the subsistence and physical and mental health. No further determination of the conditions and level of assistance provided is made. According to the relevant authorities, a decision will be made at ministerial level determining both the conditions and level of assistance, which will once again be beyond the provisions of the law. This decision has not yet been issued. As in the case of Malta, this determination must urgently be made.

Reception conditions may be reduced or withdrawn by a decision of the Asylum Service following an individualized, objective and impartial decision, which is adequately justified and announced to the applicant. Such a decision is subject to the provisions of the Convention on the Rights of the Child as it was ratified by the legislature. However, there are no guidelines regulating the implementation of that possibility. This might lead to the enjoyment of material reception conditions by children to be dependent on their parents’ access to them. Therefore, there must be legislative action taken in order to precisely determine how and to what extent material reception conditions might be reduced or withdrawn when children are concerned.

Asylum seekers are also entitled to access the labour market six months after the submission of their application. While the law grants Cypriot authorities the power to place restrictions and conditions on the right to employment without hindering asylum seekers’ effective access to the labour market, such decisions remain to be issued. As a result, the previous legislation regulating access to the labour market is still being used. The Cypriot legislation must urgently be enhanced on this point, in order for asylum seekers to enjoy an actual right to access the labour market, as required under the Directive.

The law also provides that all asylum seeking children have access to primary and secondary education under the same conditions that apply to Cypriot citizens, immediately after applying for asylum and no later than three months from the date of submission. Interestingly, the right of enrolled students to attend secondary education is not affected by age. According to the law, an assessment is made in order to decide the grade in which the students will be registered, based on their age and their previous academic level. Classes at public schools are taught in Greek and the language barrier is often difficult to overcome for the children. However, the Cypriot authorities have provided for transitional Greek classes, which are taught at all educational levels.

|

Minor asylum seekers receiving classes of Greek in a Cypriot school. |

Asylum seekers without adequate resources are also entitled to free medical care in public medical institutions covering at a minimum, emergency health care and essential treatment of illnesses and serious mental disorders. Furthermore, asylum seekers without adequate resources who have special reception needs are also entitled to necessary medical or other care free of charge, including appropriate psychiatric services. These legal provisions have to be welcomed and appropriate measures be taken towards their implementation.

Regarding special reception needs of vulnerable groups, the law defines those who might be considered as vulnerable and introduces a mechanism to identify such persons. Specifically it provides that an individual assessment shall be carried out to determine whether a specific person has special reception needs and/or requires special procedural guarantees, and the nature of those needs.

Additionally, Cypriot legislation allows relatives, advocates or legal advisors, representatives of UNHCR and formally operating NGOs to communicate with the residents of the reception centre, thus complying with the prerequisites of the Directive.

In regards to detention, Cypriot law prohibits detention of asylum applicants for the sole reason that they are applicants and also prohibits detention of child asylum applicants. Unfortunately, while specific safeguards are provided for children, this does not apply to other vulnerable groups. More specifically, there is no prohibition of detention of vulnerable persons. The latter vacuum might result in the detention of victims of torture, human trafficking or pregnant women. Detention of asylum seekers is based on an administrative order and not a judicial order and is permitted for specific instances that reflect those in Directive 33.

One of the grounds for detention prescribed in the law is the “risk of absconding”. Nonetheless, this notion is not clearly defined and the law does not provide any criteria to determine whether there exists such a risk. Furthermore, the law stipulates a non-exhaustive list for alternatives to detention, while it dictates that detention should only be used as a last resort. Nevertheless, the law does not provide for any guidelines or procedures to determine whether detention actually constitutes a measure of last resort and assess whether other measures could be applied. Another problematic provision concerns the duration of detention; the law is confined to stipulating that detention shall last only for the minimum period possible and only as long as the reasons for such detention are still in place. The law shall be amended to provide for a maximum length for detention. Such an important point shall not be left unregulated.

The law provides for a judicial review of the detention order, but legal aid is not provided in all cases. If detention is ordered based on the asylum seeker being declared a “prohibited immigrant”, then he or she is not eligible for legal aid. An applicant can apply for legal aid only when the detention order is based on the Returns Directive or Refugee Law. This point must be amended, and free legal assistance be provided to all asylum seekers who have been detained.

As in the case of Malta, Cyprus has quite adequately incorporated Directive 33 into its national legal order. However, a lot remains to be done and certain points have to be further elaborated and regulated. Particularly in the case of vulnerable persons, the legislation must become more precise and additional safeguards must be provided. Last but not least, amendments shall be made regarding the provision of material reception conditions, which should begin upon the arrival of asylum seekers.

4. Italy

a) Directive 32

Italy has transposed Directive 32 through Legislative Decree 142/2015 on the “Incorporation of Directive 2013/33/EU on standards for the reception of asylum applicants and the Directive 2013/32/EU on common procedures for the recognition and revocation of the status of international protection” (hereinafter referred to as LD 142/2015). As in the case of Cyprus, Articles 31(3)-(5) are to be transposed by 20 July 2018. LD 142/2015 was further amended at certain points –mostly regarding appeals- by Decree-Law 13/2017, which was later converted to Law 46/2017.

Italian legislation does not set a time frame for lodging an asylum request when the person is already in Italian territory. However, if a person arrives at the border in order to seek international protection, he has eight days to lodge an application. Notably, Italian legislation sets shorter time limits, compared to the three legislations examined above, for the National Commission for the Right of Asylum (NCRA) to interview the applicant and issue a decision. Nonetheless, this time limit may be extended to a maximum of 18 months.

An apparent deficiency in Italian asylum legislation regards the right to appeal. Asylum seekers can appeal a negative decision issued by the Territorial Commissions within 30 days before the competent Civil Tribunal, which does not exclusively deal with asylum appeals. Therein arises the first problem. Although asylum seekers have access to a judicial body which examines their application both in facts and in law, this judicial body is already overloaded with cases. A new judicial body should be established in order to examine the asylum seekers’ claims, rather than adding to the workload of the suffocated Civil Tribunals. If this measure is not undertaken, it is not only the examination of asylum appeals that will be hindered, but the civil cases before the pertinent tribunals will also be delayed. Another problematic aspect of the appeals procedure is that applicants placed in detention facilities and those under the accelerated procedure have only 15 days to lodge an appeal, namely half of the time limit provided to applicants under the regular procedure. This provision hampers the right to judicial access and to a fair trial, as protected under Article 6 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

LD 142/2015 prescribed that if the appeal was dismissed, it could be appealed at the Court of Appeal within 30 days of the notification of the decision. A final appeal before the highest appellate court (Cassation Court) could be lodged within 60 days of the notification of the dismissal of the previous appeal. According to Law 46/2017, Civil Tribunal decisions cannot be appealed before the Court of Appeal but only before the Court of Cassation within 30 days. In addition, Law 46/2017 stipulates that the request for the suspensive effect of the decision has to be decided by the judge who rejected the appeal. Although this provision was certainly voted to ensure the rapid processing of asylum cases, it is profoundly harsh towards the asylum seekers, who now have only one chance to fight a negative decision in court. The same second instance that is guaranteed in the case of trivial neighbour disputes is to be denied in cases that could be accurately described as life-or-death situations. Law 46/2017 also states that only 26 specialised court sections in Italy will deal with asylum appeals. While it might seem that this constitutes a step forward from the existing problematic appeals procedure, giving jurisdiction over asylum appeals only to specialised judicial bodies, the procedure before this courts raises further concerns. Law 46/2017 foresees no obligation for asylum seekers to appear before the judges, allowing the judges’ decision to be based on the video-recording of the applicants’ interviews with the Territorial Commission. As a result, asylum seekers’ right to defence is substantially curtailed, thus limiting their effective access to justice. It cannot be seen how abolishing the need for a hearing with the appellant abides with the Directive. The latter stipulates that an appeal includes a complete, non-retroactive examination of all factual and legal elements. It is rather absurd to conclude that this prerequisite may be fulfilled through the mere examination of a video recording of the interview before a purely administrative organ.

|

Asylum seekers requesting freedom of movement in the EU. |

An important amendment under LD 142/2015 is that it stipulates that the obligation to inform the police of the domicile or residence is fulfilled by the applicant by means of a declaration, to be made at the moment of the application for international protection and that the address of the accommodation centres is to be considered the place of residence of asylum applicants who effectively live in these centres. This provision simplified the registration of asylum seekers, who were previously required to have indicated a residence, in order to apply for protection. LD 142/2015 provides for a prioritised and an accelerated procedure, which do not present any particularities. The only point that is worth pointing out is that the law does not clarify whether the procedure can be declared accelerated even if the procedure and the time limit set out in the law have not been respected. Furthermore, the provisions regarding the personal interview do not diverge much from Directive 32. As in other national legislations, LD 142/2015 stipulates that the interview may be recorded. Notably, it is foreseen that the recording is admissible as evidence in judicial appeals. This is not necessarily a positive aspect, since this recording is the only evidence which is examined by the court, as already noted.

Remarkably, LD 142/2015 did not change the previous legal framework in terms of legal assistance. It states that asylum seekers may benefit from legal assistance and representation during the first instance of the regular and prioritised procedure at their own expense. There is no legal provision for free legal assistance during the first instance. At least free legal assistance is provided under the appeals procedure. It is worth underlining that under Law 46/2017 when the applicant is granted free legal aid, the judge, when fully rejecting the appeal, has to explain why free legal aid is awarded, indicating the reasons why he or she does not consider the applicant's claims as manifestly unfounded.

It must be underlined that the “safe country” concepts are not applicable in the Italian context. Additionally, it must be pointed out that LD 142/2015 has increased the maximum duration of asylum seekers’ detention: according to the law asylum seekers can be detained up to 12 months. Moreover, LD 142/2015 describes the following groups as vulnerable: minors, unaccompanied minors, pregnant women, single parents with minor children, victims of trafficking, disabled, elderly people, persons affected by serious illness or mental disorders; persons who have experienced torture, rape or other serious forms of psychological, physical or sexual violence; victims of genital mutilation. Unfortunately, there is no procedure defined in law for the identification of vulnerable persons, apart from certain provisions regarding unaccompanied minors. Furthermore, special care and assistance is foreseen for victims of torture, rape, trafficking or other forms of violence.

To sum up, Italy seemed to take steps forward by transposing Directive 32 through LD 142/2015. There are undeniable gaps in this legislation, which have to be filled in by future legislative attempts. Nevertheless, the recent Law 46/2017 constitutes a U-turn in Italy’s intentions. It can be claimed that Italy sees itself as the first point of entry in “Fortress Europe”, which is unable to host any more illegal immigrants and is ready to accept only a small number of refugees –those who can definitely support that they are ‘genuine’ refugees. No adequate remedies are provided to asylum seekers, who may see their claims being denied under the new procedure, without a real chance to appeal against the negative decision. Italy’s Law 46/2017 does not simply constitute a legislative failure. It reflects a change of perspective of the Italian authorities regarding international protection, which is even more alarming.

b) Directive 33

Italy has also transposed Directive 33 through LD 142/2015. In Italy, there is no uniform reception system. LD 142/2015 articulates the reception system in phases, distinguishing between:

1. Phase of first aid and assistance, operations that continue to take place in the centres set up in the principal places of disembarkation,

2. First reception phase, to be implemented in existing collective centres or in centres to be established by specific Ministerial Decrees or, in case of unavailability of places, in “temporary” structures and

3. Second reception phase, carried out in the structures of the System of Protection for Asylum Seekers and Refugees (SPRAR) system. The SPRAR, established in 2002 by Law 189/2002, is a publicly funded network of local authorities and NGOs which accommodates asylum seekers and beneficiaries of international protection.

According to LD 142/2015, first reception is guaranteed in the governmental accommodation centres in order to carry out the necessary operations to define the legal position of the foreigner concerned. LD 142/2015 provides for first aid and accommodation structures. The Italian legislation does not determine the maximum duration of asylum seekers in the first aid and assistance centres. It is confined to stipulating that applicants shall stay “as long as necessary” to complete procedures related to their identification or for the “time strictly necessary” to be transferred to SPRAR structures. There is an urgent need for elaboration on these abstract notions and the provision of a maximum time limit regarding the stay of asylum seekers in the centres of first aid and assistance, where they cannot remain trapped for an indefinite period of time.

It is important to underline that LD 142/2015 makes special provision for trafficked asylum seekers. The latter are entitled access to a special programme of social assistance and integration.

LD 142/2015 stipulates that applicants are entitled to material reception conditions from the moment they manifested their willingness to make an application for international protection. Material reception conditions shall be provided solely on this basis and no further requirements must be fulfilled. The latter does not apply regarding access to SPRAR centres. In order for applicants to gain access to the centres, they must be considered destitute. This characterization is granted after an assessment by the authorities.

With regard to appellants, LD 142/2015 provides that accommodation is ensured until their application is decided and, in case of rejection of the asylum application, until the expiration of the time frame to lodge an appeal before the judicial court. When the appeal has an automatic suspensive effect, accommodation is guaranteed to the appellant until the first instance decision taken by the Court. When this is not the case and the appeal does not have an automatic suspensive effect, the applicant remains in the same accommodation centre until a decision on the suspensive request is taken.

The applicant detained in a pre-removal detention centre who makes an appeal and a request of the suspensive effect of the order, if accepted by the judge, remains in the reception centre. Where the detention grounds are no longer valid, the appellant is transferred to governmental reception centres.

The law stipulates that first reception centres generally offer basic services compared to those provided by second-line reception structures (such as SPRAR). Such basic services include food, accommodation, clothing and basic information services, including legal services, first aid and emergency treatments. These centres ensure respect for private life, including gender, age, physical and mental health, family unity, prevention of forms of violence and violence.

|

African asylum seekers waiting in line to receive a meal outside of Centro Astalli. |

Some notable deficits of the law is that it does provide a definition of “adequate standard of living and subsistence” and does not envisage specific financial support for different categories, such as people with special needs. Moreover, it does not provide any financial allowance for asylum applicants needing accommodation. This results in overcrowded facilities, since every applicant attempts to secure a place in the reception centres.

LD 142/2015 also determines the criteria for reducing or withdrawing reception conditions, according to the prerequisites of Directive 33. Unfortunately, there is no provision for an assessment of destitution risks during this procedure. Notably, applicants who have seen their reception conditions been withdrawn or reduced may lodge an appeal against this decision before the Regional Administrative Court. They are also entitled to free legal aid to this end.

Furthermore, the Italian legislation ensures that asylum seekers enjoy freedom of movement throughout the Italian territory. Exceptionally, the competent authorities may issue a specific order to delimit the movement of an asylum seeker within a certain place of residence or a geographic area. Notably, according to Article 10(2) LD 142/2015, in the first reception centres asylum seekers are allowed to leave the facilities during the day with the obligation to return in the evening hours.

The provisions of LD 142/2015 regarding the access to the labour market must be welcomed. The law foresees that asylum seekers have the right to start working 60 days subsequently to the day they lodged their application. Nonetheless, even if they get employed, their stay permit cannot be converted in a work stay permit. The law is very general in determining the procedure to access the labour market and does not stipulate any limitations. Asylum seekers in Italy may seek employment in any sector. Moreover, Italian legislation provides for vocational trainings for asylum seekers living in SPRAR facilities.

LD 142/2015 also ensures that unaccompanied asylum-seeking children and children of asylum seekers have the right to attend the Italian education system and are also admitted to Italian language courses. Notably, LD 142/2015 stipulates that all provisions concerning the right to education and the access to education services apply to foreign children as well. No preparatory classes are provided for at the national level, but since the Italian education system envisages some degree of autonomy in the organisation of the study courses, it is possible that some institutions organise additional courses in order to assist the integration of foreign children.

Furthermore, the Italian legislation states that asylum seekers enjoy equal treatment and the same rights and obligations as Italian citizens regarding the mandatory contributory assistance provided by the National Health Service in Italy. Prior to lodging an application and while their enrolment is pending, asylum seekers have access to emergency care and essential treatments and they benefit from preventive medical treatment programmes aimed at safeguarding individual and collective health. Asylum seekers have to register with the national sanitary service in the offices of the health board competent for the place in which they declared to have a domicile. Once registered, they are provided with the European Health Insurance Card, whose validity is related to the permit of stay. Unfortunately, there is no legal provision regarding the renewal of the right to medical care, which is dependent on the renewal of the accommodation. Therefore, applicants whose permit of stay is not renewed, also have no access to medical assistance, apart from urgent sanitary treatments. While the procedure for the renewal of the permit to stay might last for a while, there is a need for a legislative provision which will grant applicants access to medical care, while the renewal of their permit to stay is pending.

Moreover, LD 142/2015 dictates that the special needs of vulnerable persons will be taken into account for the provision of accommodation. Nonetheless, there is no further elaboration on how and by whom this assessment will be conducted. This vacuum in the Italian legislation should be urgently filled.

In regards to detention of asylum seekers, according to LD 142/2015, they shall not be detained for the sole reason of the examination of their application. The law specifically determines the grounds on which detention is justifiable. As in the cases of Greece and Cyprus, the “risk of absconding” is stipulated as one of the reasons for detention. However, as in the two aforementioned cases, this notion requires further clarification by the Italian law. The Italian legislation also provides for alternatives to detention. Nevertheless, it is remarkable that even though the Return Directive foresees detention only as a last resort where less coercive measures cannot be applied, in transposing the Return Directive, Italian legislation envisages forced return as a rule and voluntary departure as an exception.

Regarding the detention of unaccompanied minors, the law explicitly stipulates that it is not permitted under any circumstances. Additionally, detention is also prohibited in the case of children living with their families. The latter may be detained together with their parents only subsequent to lodging a pertinent request or when a Juvenile Court decides so. LD 142/2015 was amended in 2017 by Law 46/2017. According to this reform, detention of vulnerable persons is absolutely prohibited. Interestingly, the law dictates that an assessment of vulnerability situations requiring specific assistance should be periodically provided in detention centres.

Concerns are raised regarding the accessibility of detention centres by third parties, particularly by journalists. The latter have to pass two stages in order to get authorization to enter the facilities. These provisions must be amended and access to detention centres be facilitated in the best interest of asylum seekers and in order for public awareness to be raised on the issue.

In sum, Italy has quite adequately incorporated Directive 33 in its legal order. In light of the numerous asylum seekers Italy receives every year, there is a need for further reform in the direction of a uniform system. It must be welcomed that Italy has taken appropriate measures to ensure protection of vulnerable asylum seekers and that access to the labour market, the education and the health system is guaranteed for all applicants. There is a need to amend the provisions regarding accommodation, as suggested above. There is also an urgent need for health care to be provided to applicants at all stages of the procedure.

Conclusion

It seems that the Directives have indeed provoked important amendments in the legislations of the south-eastern EU countries. All four states have voted and enacted legal instruments, which are intended to transpose the standards set by the Directives.

In the case of Directive 32, in Greece and Malta, the pertinent efforts have been concluded quite successfully. Regarding Cyprus, it must be underlined that much progress has been made through the 2016 laws. However, Geneva International Centre for Justice wishes to point out that much more must be done in the near future in order to ensure State compliance with EU law and consequently better manage the serious refugee crisis. The situation in Italy seems to be more ominous; while Italy initially attempted to transpose Directive 32 in a relatively successful fashion, the recent legislation raises legitimate concerns. Geneva International Centre for Justice recommends to the Italian authorities amend their policy and adopt a more open approach to asylum seekers.

With regards to Directive 33, in the case of Greece, Geneva International Centre for Justice urges the Greek government to proceed with fully incorporating the Directive into its national legislation. It is unacceptable that only three Articles of Directive 33 have been transposed hitherto, while almost three years have lapsed since the deadline for the transposition of the Directive. Furthermore, Geneva International Centre for Justice suggests that Greece reviews its legislation regarding the detention of asylum seekers. Malta appears to be the State which has reacted more appropriately to the prerequisites set by the European Union. Cyprus and Italy have quite decently incorporated Directive 33 into their national legal orders. Nonetheless, Geneva International Centre for Justice wishes to stress that they should still review their legislation and elaborate further on certain aspects, while also adding new provisions. Geneva International Centre for Justice suggests that the two States build upon the legislation they have already voted for.

It is certain that the incorporation of the Directives constitutes only the beginning of compliance with the agreed legal and policy EU plan for handling the refugee crisis. All four South-Eastern EU States must review their national legislation as soon as possible in order to ensure that the efforts of the rest of EU countries do not rest upon a problematic basis in some of the first points of entry in Europe. While in some cases the 4 south-eastern EU States shall not diverge much from the legislation they have already enacted, there is considerable room for improvement in most cases, as already analysed. All four States must, above all, take administrative measures to ensure that their asylum legislation is enforced.

It must be underlined that even though the Directives establish common procedures for granting and withdrawing international protection and for granting reception conditions to asylum seekers, this should therefore not be interpreted as denying Member States any room for making effective use of more favourable provisions. In other words, the Directives set the lower threshold for procedures for granting and withdrawing international protection and for reception conditions. The Member States enjoy an unlimited margin of discretion in applying more favourable provisions than the ones stipulated by the Directives –as long as they take the necessary measures to ensure that at least the standards set by the Directives are met.